Analysis: COVID-19 Fears Hit Wall Street and Main Street, but Consumer Confidence Fell Faster

This analysis was authored by Morning Consult economist John Leer.

The recent stock market rally has caused many to conclude financial markets do not reflect the fundamentals of the real economy. Since March 23, the S&P 500 has regained just over half of what it lost during the sell-off that began Feb. 19. During that same time period, the United States has witnessed record-high levels of unemployment, a sharp decrease in consumer spending and a rapid contraction in manufacturing output.

While these real economy metrics provide valuable insight, they do not lend themselves to a quantification of the gap in confidence between Main Street and Wall Street. Stock market prices reflect forward-looking assessments of all available information whereas most economic data is backward-looking and focuses on a single sector or aspect of the economy. Consequently, it is not appropriate or feasible to use these metrics to quantify the difference between the stock market and the real economy.

Such a quantification is important for measuring the impact of COVID-19 on Wall Street and Main Street. These measurements allow businesses and policymakers to allocate and prioritize investments and policy interventions across financial markets and the real economy.

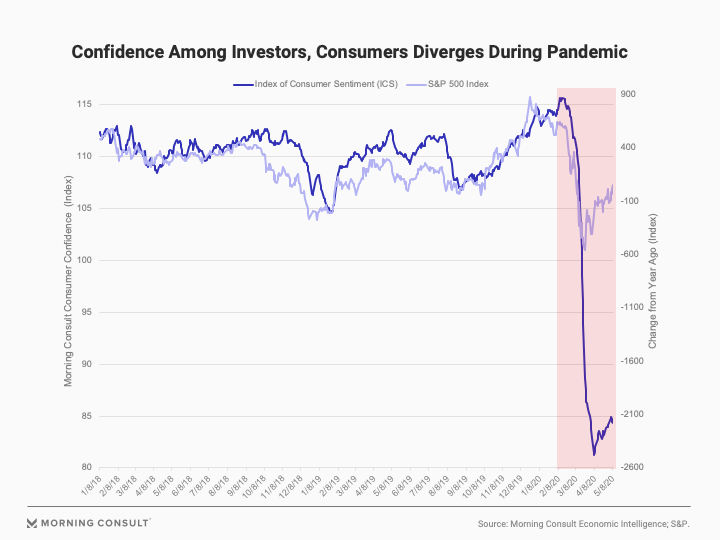

To make these calculations, it’s not as simple as directly comparing trends in the S&P 500 Index with Morning Consult’s daily Index of Consumer Sentiment (ICS), for reasons I’ll explain later in this analysis. But after transforming the S&P 500 data to make for a better theoretical and empirical comparison with the ICS data, I show that the coronavirus pandemic has created the largest disconnect between consumers and investors since this dataset began in January 2018. From peak to trough, consumer confidence fell by 20 times its pre-COVID daily standard deviation, whereas stock prices fell by only six times.

The recent divergence between investor and consumer confidence is particularly surprising given the historic correlation over time. The correlation between the ICS and the S&P 500 Index is 0.67 from Jan. 7, 2018 to May 10, 2020. Consumer confidence of high-net worth individuals (i.e, those with over $500,000 invested in the stock market) is more highly correlated with the S&P 500 than the general population (0.76 vs. 0.67).

These results are relevant to current economic and policy debates for two reasons. First, they provide an objective approach to measuring the relative impact of the coronavirus on equity markets and consumers. The fact that consumers’ and investors’ responses are highly correlated over time makes the recent divergence even more meaningful. While consumers and investors often view the world similarly, their financial and economic assessments have diverged over the past two months.

Second, this daily comparison of investor and consumer confidence allows policymakers to better understand the effects of policy interventions -- both proposed and implemented -- on investors’ and consumers’ outlooks. If the U.S. economy is going to rebound, policies must not only address the challenges on Wall Street, but also those on Main Street. This graph shows that perceptions and expectations on Main Street are in a worse position than those on Wall Street.

The remainder of the analysis dives into the theoretical and empirical justification for adopting the approach presented in the graph above.

Consumer confidence and stock prices: What do they measure?

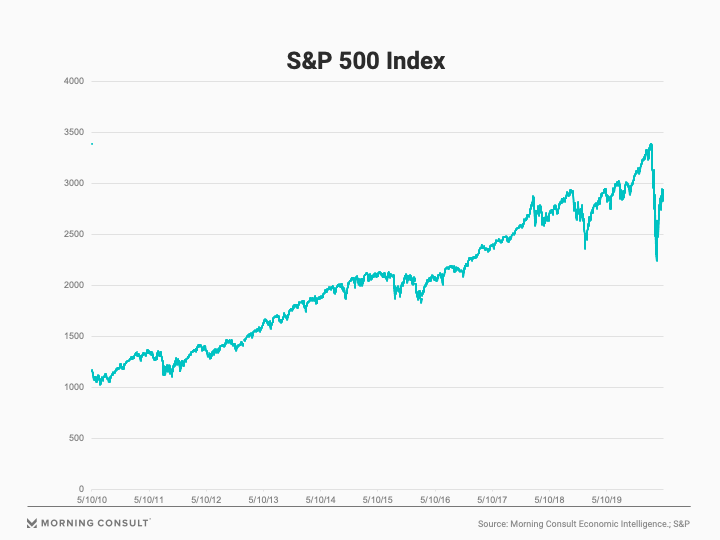

S&P 500 Index

The S&P 500 is an index of the top 500 publicly listed U.S. companies in terms of their market capitalizations. Changes in the value of the S&P 500 primarily reflect changes in the share prices of the companies included in the index. [1] There are many different theories regarding stock price valuation, but most finance textbooks still rely on some form of fundamental analysis to value stocks. According to this method, a company’s stock price reflects the present discounted value of all of its future profits. The discount rate drives the relative importance of near-term versus long-term profits. All else equal, a higher discount rate decreases the present value of future profits.

Thus, the S&P 500 reflects the present discounted values of all expected future corporate profits of companies included in the index. While the time horizon covers all future profits, the discount factor ensures that profits far out into the future (for example, over 10 years) are less valuable than near-term profits.

There are two primary obstacles to measuring the recent divergence between the stock market and the real economy. First, investors are forward-looking while economic data is largely backwards-looking. If investors believe that unemployment will rapidly decrease in the near future or that consumer spending will rebound, then they’re likely to discount the data releases.

Second, investors incorporate all data available to them to arrive at a price. Unemployment, consumer spending and manufacturing output are important drivers of stock prices over long periods of time, but daily news also influences prices. This data aggregation challenge is particularly important now given that the path of the economy is so highly dependent on the country’s health response to the pandemic.

Morning Consult U.S. Consumer Confidence

Morning Consult’s daily consumer confidence provides a solution to these measurement challenges. Since the data is updated daily, consumers’ views are informed by all available information, including daily news developments.

Additionally, just as stock market prices reflect investors’ views of companies’ future profits, consumer confidence is primarily forward-looking. Three of the five questions used to measure consumer confidence ask consumers to report their views of future business conditions in the country as a whole and of their future personal finances. The Index of Consumer Expectations (ICE) exclusively reflects consumers’ future expectations.

Unlike the S&P 500, the time horizons of the future-oriented consumer confidence questions are bounded by a window of either one or five years into the future. Over a shorter, bounded time period like one to five years, consumers’ assessments reflect cyclical developments in the economy rather than long-run secular trends. Consequently, consumer confidence, even the expectations components, vary over the course of the business cycle and do not exhibit long-run trends.

The same is not true of the S&P 500. It exhibits a positive trend over time. In other words, investors’ expectations of the present value of future profits tend to increase over time, even after accounting for the decreases experienced during past recessions.

How to compare investor and consumer confidence?

The presence of a long-run positive trend in the S&P 500 Index means that it is not appropriate to directly compare its values with Morning Consult’s ICS. The positive trend means that future values of the S&P 500 tend to be higher than current values regardless of the cyclical position (i.e., expansion or contraction) of the U.S. economy.

From a theoretical and empirical perspective, the best solution to removing the long-run, positive trend in the S&P 500 is to look at differences over time. In particular, analyzing changes from a year ago in daily closing values of the S&P 500 Index provides the most appropriate approach to comparing investor and consumer sentiment. The reference period for these values more closely matches that of consumer confidence.

These values reflect investors’ expectations of future corporate profits relative to their expectations from 12 months ago. In other words, how have investors’ future expectations changed over the past 12 months? Similar to the ICS, this perspective is both forward- and backward-looking since it builds an assessment of the future relative to the past.

This transformation of the S&P 500 also achieves the empirical properties necessary to compare it to daily consumer confidence. Namely, it exhibits no clear long-term trend.

Key findings

There is a strong positive correlation between Morning Consult’s daily Index of Consumer Sentiment and the S&P 500. While Morning Consult’s consumer expectations index outperforms the ICS during certain periods of the time, the ICS is the more consistently highly correlated with the S&P 500.

The correlation increases from 0.61 to 0.67 by moving from a coincident correlation to a five-day lag between the S&P 500 and consumer confidence. There are three reasons for this temporal relationship between the S&P and consumer confidence. First, most of the surveys taken on a given day are processed and recorded the following day. For example, if the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases skyrockets on Monday, that information is reflected at the very earliest in the data on Tuesday.

Second, Morning Consult’s daily ICS is a seven-day exponentially weighted moving average. It takes seven days after an event occurs for all survey respondents to potentially be aware of the event. As each day passes, a greater share of surveys is taken after a given event in the past occurred. Not surprisingly, the correlation between the S&P 500 and Morning Consult’s ICS decreases after the full seven-day period. The raw, daily consumer confidence data is less likely to exhibit the same lag/lead relationship with the S&P.

Third, there is a higher share of consumers aware of daily changes in the S&P 500 than there is of investors aware of daily changes in consumer confidence. Consumers regularly cite changes in the stock market as driving their views of business conditions in the country as whole. While some investors previously focused on monthly consumer confidence data, this practice is not as common as it once was due to changes in the availability of data. As governments and the private sector continue developing and releasing higher frequency economic indicators, the temporal relationship between daily consumer confidence and the S&P 500 is likely to evolve.

Consumer confidence among Americans with stock market investments is more highly correlated with the S&P 500 than average consumer confidence. The more money consumers have invested in the stock market, the more closely changes in their economic outlook resemble changes in the S&P 500.

Somewhat surprisingly, wealthier consumers do not update their outlooks any sooner than consumers with less money invested in the market. Similar to the general population, consumer confidence of high-net worth individuals (i.e., those with over $500,000 invested in the stock market) is most highly correlated with the closing value of the S&P 500 five days prior.

In the short run, this divergence between Main Street and Wall Street economic perceptions indicates that consumer spending, consumer finances and employment are all likely to suffer more than corporate profits. From a policy perspective, it also indicates that Main Street requires additional assistance from policymakers. Historically, the outlooks of consumers and investors responded similarly to policy interventions, albeit with different timing. However, the current situation is not merely a matter of timing. Barring a policy interventions, the gap appears to be the new normal, which is an ominous sign for the U.S. economy.

In the long run, a persistent gap between outlook on Wall Street and on Main Street is not sustainable. A lack of consumer spending and widespread weaknesses in households’ balance sheets erode corporate profits and weaken investors’ outlook. In other words, history indicates that the gap will close over time, and prolonged periods of low consumer sentiment suggest that investor confidence is likely to fall before consumer sentiment rises.

[1] S&P updates the weights assigned to companies in the S&P 500 so that changes in the index value represent changes in the stock market more broadly. When the S&P 500 was first launched in 1957, companies like Amazon and Google did not exist. If S&P never updated the list of companies, the S&P 500 would not include Amazon or Alphabet. Those companies now have some of the largest market capitalizations. By adjusting the index weights, a $1 change in the price of Apple stock has a larger effect on the value of the S&P 500 than a $1 change in the price of a smaller company. For a discussion of the judgment involved in administering the S&P 500 index, see De Silva’s “The art and science of stewarding the S&P 500”.

John Leer leads Morning Consult’s global economic research, overseeing the company’s economic data collection, validation and analysis. He is an authority on the effects of consumer preferences, expectations and experiences on purchasing patterns, prices and employment.

John continues to advance scholarship in the field of economics, recently partnering with researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland to design a new approach to measuring consumers’ inflation expectations.

This novel approach, now known as the Indirect Consumer Inflation Expectations measure, leverages Morning Consult’s high-frequency survey data to capture unique insights into consumers’ expectations for future inflation.

Prior to Morning Consult, John worked for Promontory Financial Group, offering strategic solutions to financial services firms on matters including credit risk modeling and management, corporate governance, and compliance risk management.

He earned a bachelor’s degree in economics and philosophy with honors from Georgetown University and a master’s degree in economics and management studies (MEMS) from Humboldt University in Berlin.

His analysis has been cited in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Reuters, The Washington Post, The Economist and more.

Follow him on Twitter @JohnCLeer. For speaking opportunities and booking requests, please email [email protected]