Food Insecurity Is Up in Europe, Raising Political Risks

Key Takeaways

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has disrupted global supply chains for inputs into food products. Our data unambiguously shows that it has already taken a substantial economic toll on European consumers, posing political risks for incumbent governments.

In the five largest European economies, more adults are experiencing food insecurity than at any time in the last year, and they are generally dissatisfied with the direction their country is heading. And in several large markets across the continent, more people are worried about the price of food than even the price of gas.

Russia’s willingness to use access to food and agricultural inputs as a geopolitical lever — specifically by opening food export corridors in Ukraine in exchange for sanctions relief — means that governments facing public pressure to lower food prices will have strong incentives to compromise with Putin, shoring up their domestic political support but potentially lengthening the war.

In the meantime, agribusiness and commodities traders should expect opposition parties across Europe to continue drawing attention to rising food prices, and should prepare for short-term policy responses like tax cuts, state aid to European agribusiness and possibly export bans.

Food insecurity in Europe is less acute than in the developing world, but it still poses policy risks

Growing global food insecurity has been in the news a lot lately, with pandemic-related inflationary pressures — exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — leading to concerns that supply side price shocks for grain and cooking oil could last well into 2023. Governments and NGOs have rightly sounded the alarm about the acute food crisis brewing for major food-importing countries across Africa and the Middle East, driven by high prices for food staples.

In wealthy countries, the strain from rising food prices is more indirect, as are its effects. The European Union in particular is mostly self-sufficient when it comes to food production, but it relies on imports of some inputs, such as feed protein and fertilizer ingredients, as well as energy. And Europeans are still feeling the strain of higher food prices.

The issue has already become a political football, both in domestic politics as opposition parties across the continent rail against rising costs of living and in geopolitics as Vladimir Putin tries to use food and fertilizer as leverage. Putin has already sought to extract concessions from European governments in the form of sanctions relief in exchange for lifting his blockade of Ukraine’s ports to allow food shipments to reach world markets. The consequences for business will be substantial, both in terms of European policy responses and overall political instability among E.U. countries as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — both countries are among the top five grain exporters globally — drags on.

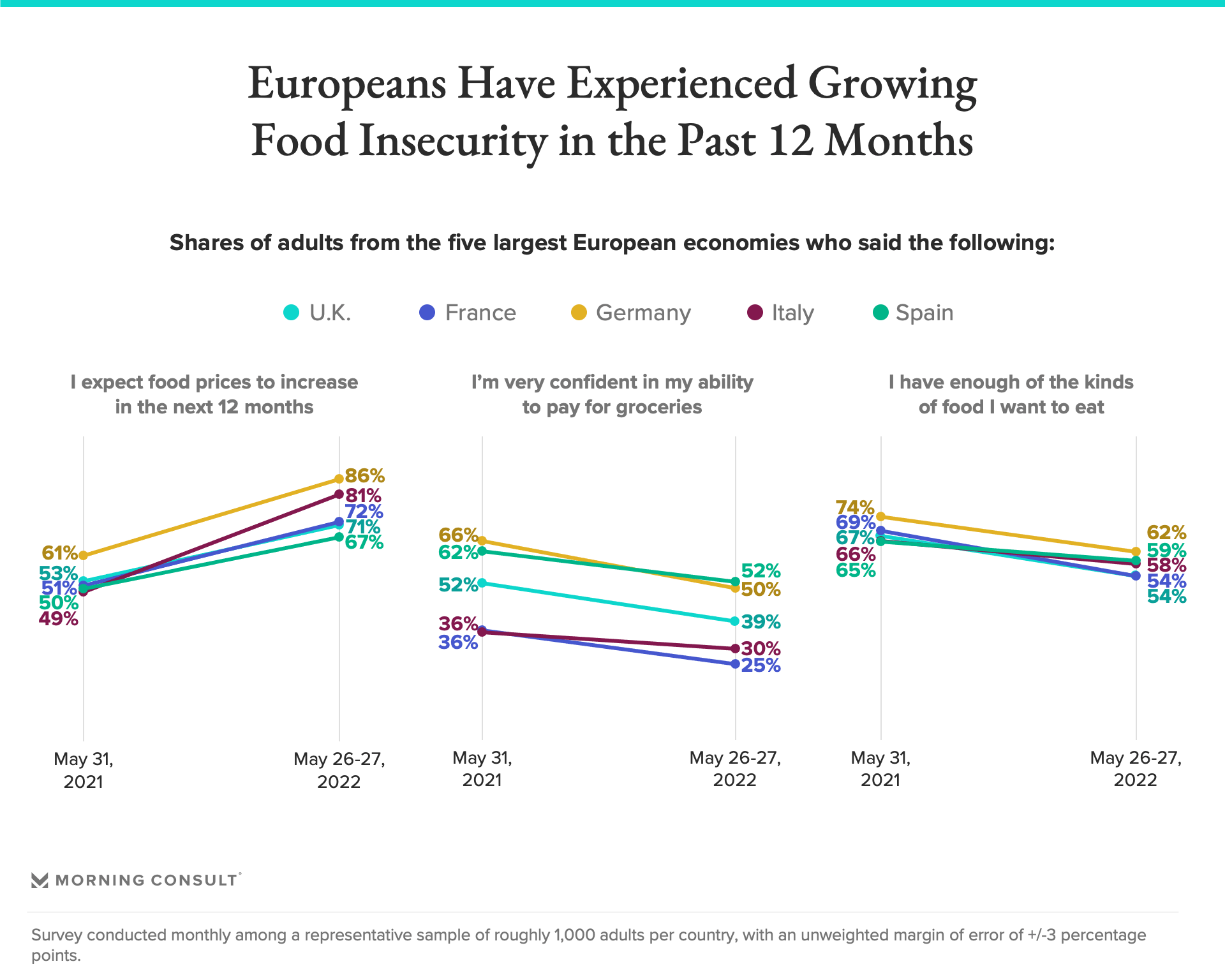

Food insecurity in major European economies is higher than a year ago

In the five largest European economies, consumers are reporting higher levels of food insecurity than at any point in the last year. Larger shares of adults in each country say they expect higher grocery bills, and smaller shares say they are “very confident” they can afford groceries and have enough of the kinds of food they want to eat. Germans have experienced some of the biggest shifts, with a whopping 25% increase in the share expecting food prices to rise in the next 12 months, a 16% drop in the share of Germans who are confident they can pay for groceries, and 12% fewer saying they have enough of the kinds of food they want to eat.

In light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there’s now more angst over food than gas in some markets

Spiking gas prices have contributed much more to the growth in headline inflation than food prices have. However, in a separate survey specifically related to policy sentiment after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, slightly more Europeans surveyed cite the price of food as a concern in light of the war than gas prices. This is likely due to coverage: Not everyone buys gas, but everyone has to eat.

Among Adults in Large European Markets, Food Prices Are a Bigger Concern Than Energy Prices

The politics of food security in Europe signal troubled times ahead as the war in Ukraine drags on

Beyond the immediate impact on consumers and their spending habits, the rising cost of living will provide fodder for opposition parties across Europe, prompting policy responses by sitting administrations to hedge against future electoral challenges at various levels of government.

The issue has played into recent elections. In April’s Hungarian presidential contest, incumbent Viktor Orban froze the prices of six basic food commodities in the lead-up to his landslide reelection. Also in April, Marine Le Pen led France’s right-wing National Front party to its strongest showing ever in the country’s presidential election, winning over 40% of the vote in the second round though failing to clinch a victory. The cornerstone of her campaign was a focus on the rising cost of living, channeling growing discontent among the French middle class. Across the European Union, the right is tapping into voters’ discontent over the cost of basic goods. This trend will continue in French parliamentary elections in June, and in a spate of national-level contests in 2023 if inflation continues to bite.

In countries without national electoral contests in the next year, sitting governments are still taking action to insulate themselves against criticism from opposition parties. In the United Kingdom, Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak took a page out of the Labour Party’s playbook, announcing a 15 billion pound ($18.8 billion) spending package to support households hit by rising costs of living, paid for by a windfall tax on energy that he had previously criticized. Italy passed a similar measure, in part taking advantage of a temporary relaxation of rules on state aid. And the Spanish and Portuguese governments successfully lobbied Brussels to allow temporary price caps on energy, which will put wind in the sails of those advocating for similar measures related to food prices, especially as they continue to soar.

Large Shares of Europeans Say Their Country Is on the ‘Wrong Track’

In Germany, despite inflation nearing a 50-year high, the political response has been relatively muted. Opposition parties — including Angela Merkel’s successors at the top of the Christian Democratic Union party — have focused instead on perceived weak handling of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in lieu of rising prices.

Sitting European governments will have to respond to cost of living complaints

As public anger grows, and as opposition parties across the continent tap into mounting discontent over rising prices and food insecurity to challenge incumbents, expect more short-term policy responses from sitting governments, including temporary increases in state aid to farmers and agricultural companies and value-added tax cuts on food. This will be a mixed bag for businesses, depending on what industry and market they’re in. While VAT reductions on food are a net positive for agribusiness generally, state aid for European agriculture and fishery companies would only benefit local entities, distorting the market for foreign competitors. Efforts to impose targeted export bans on food commodities also continue to crop up — even though the European Union formally opposes such bans. If they are imposed, food exporters face substantial losses.

Judging by recent comments in the European Commission, the European Union could also revisit provisions of the 2014 MiFID II regulation related to speculation in food commodity markets if prices continue to rise. This regulation was passed after the last sustained period of major food inflation from 2010 to 2014, and places limits on position sizes for food derivatives. Affected industries would include financial services and commodities.

On the geopolitical side, the temptation faced by European officials to cave to Russian demands for sanctions relief in return for a “humanitarian food corridor” will grow in tandem with political pressure on governments to contain prices. Much like demands for gas payments in rubles, this measure is designed to give Russia fiscal breathing room. While it might seem like an immediate positive for businesses insofar as it would prevent some harmful short-term policy fixes, granting sanctions relief would allow Russia to fund its war effort, lengthening the conflict. That long-term cost would far outweigh any short-term gain.

Sonnet Frisbie is the deputy head of political intelligence and leads Morning Consult’s geopolitical risk offering for Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Prior to joining Morning Consult, Sonnet spent over a decade at the U.S. State Department specializing in issues at the intersection of economics, commerce and political risk in Iraq, Central Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. She holds an MPP from the University of Chicago.

Follow her on Twitter @sonnetfrisbie. Interested in connecting with Sonnet to discuss her analysis or for a media engagement or speaking opportunity? Email [email protected].