India in Between: Modi’s Delicate Dance of Diplomatic Moderation Offers Risks and Rewards

Key Takeaways

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has cast a spotlight on India’s strategic importance and nonalignment. The political ambiguities this entails are reflected in Indian public sentiment about the country’s relations with both Russia and China.

Indian adults have similarly warm views of the United States and Russia, and while a plurality of Indians blame Russia for the war in Ukraine, the combined share who blame the United States and NATO is larger.

Indians, meanwhile, view China and the United States as their country’s top two threats above even Pakistan, indicating public wariness of being drawn into a conflict between the global powers.

India’s middle path, coupled with its market scale and regional access, offer net benefits for multinationals rethinking their investments in China. But drawbacks persist owing to its position on the periphery of the Western industrial policy clique.

When possible, foreign companies — and particularly those in industries Western governments view as strategic — should consider India as one of many investment destinations but hedge their bets and diversify their supply chains more broadly to mitigate risks arising from the country’s complicated diplomatic position.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sparked a second act for Indian nonalignment

The April 7 vote to suspend Russia from the U.N. Human Rights Council revealed familiar geopolitical fault lines between the West and the rest. For multinational corporations with globe-spanning supply chains, workforces and consumer bases, the apparent resurgence of Cold War-era spheres of influence is troubling.

Political analysts rushed to declare that many countries’ decisions to abstain or vote against Russia’s expulsion (82 in total) was a clear display of the growing momentum behind version 2.0 of the Non-Aligned Movement, whereby a group of developing nations professed to maintain a neutral foreign policy during the Cold War. But the makeup of the global order is different today than during that era: China, not Russia, is the gravitational center for those opposing the West.

The largest of the Cold War nonaligned countries — by virtually any measure — is India. The South Asian giant is once again trying to chart a middle path, using its close ties with Russia and the United States to balance against China, while at the same time striving to prevent conflict between the latter two countries, which regularly switch positions as its top trading partner.

India’s top trading partners are also its top security concerns

A near majority of Indian adults (43%) view China as their country’s greatest military threat. Sino-Indian tensions have run hot since shortly after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, when its annexation of Xinjiang and Tibet led to still-unresolved border disputes with India. A bloody war in 1962 marked the beginning of periodic hostilities that have shaped India’s military and strategic outlook ever since. A quarter-century détente in the name of economic development and cooperation during the height of China’s reform era began to evaporate around 2012 with the arrival of new leader Xi Jinping, who has implemented an increasingly assertive vision for Chinese foreign policy. Renewed border tensions ensued, leading to the first combat fatalities between the two sides in 45 years, souring relations and prompting India to ban numerous Chinese tech companies (though it claimed these moves were more about national security concerns). Despite high-level talks and a brief meeting between the two nations’ leaders on the sidelines of the G-20, tensions — and the possibility of further armed conflict — remain high.

Indians Perceive China and the United States as Their Country’s Biggest Threats

Although China’s conflict with India has in some ways pushed New Delhi closer to Washington, in a striking finding, nearly a quarter of Indian adults (22%) actually see America as India’s greatest threat. As the next largest share, the United States clocks in higher than even historical nemesis Pakistan (13%).

While the world’s two largest democracies would seem to make for natural partners, especially given their mutual mistrust of China, Indians have strategic reasons to be wary of the world’s Western superpower: As tensions between Washington and Beijing increase, the Indian public may be worried about getting caught in the middle of a U.S.-China conflict that destabilizes regional security, putting India at risk.

India’s simultaneous memberships in both the U.S.-backed Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, commonly called the Quad, and the China- and Russia-backed Shanghai Cooperation Organization are together a good example of its pragmatic approach to dealing with the dueling powers, in part to help mitigate the aforementioned risk.

On the one hand, India’s Quad membership — alongside Japan, Australia and the United States — nominally aligns it with the major Western democracies hoping to contain China’s rise in the Asia-Pacific region. But India has been adamant that the Quad is merely a functional collective as opposed to a tight-knit group of nations underpinned by shared democratic values, as other members have argued. According to our own research, public faith in the Quad among its member states — as both a regional and national security stabilizer — remains limited in Asia, with Indians again of mixed minds.

On the other hand, in 2017 India joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, originally a Central- Asia-focused security arrangement that some have described as an “anti-U.S. bulwark” in the region. Reinforcing the point, Iran and Belarus — both Russia-aligned foes of the United States — are expected to accede to full SCO membership.

Sleeping in the middle makes for strange bedfellows

India’s renewed attempts to carve out a middle path have come with a curious array of foreign policy affinities and enmities, in part by design. It cannot afford an unchecked alliance between Russia, China and Pakistan, and it relies on positive relations with Russia — which supplies India with affordable energy and military hardware — to help temper Chinese aggression and expansionism.

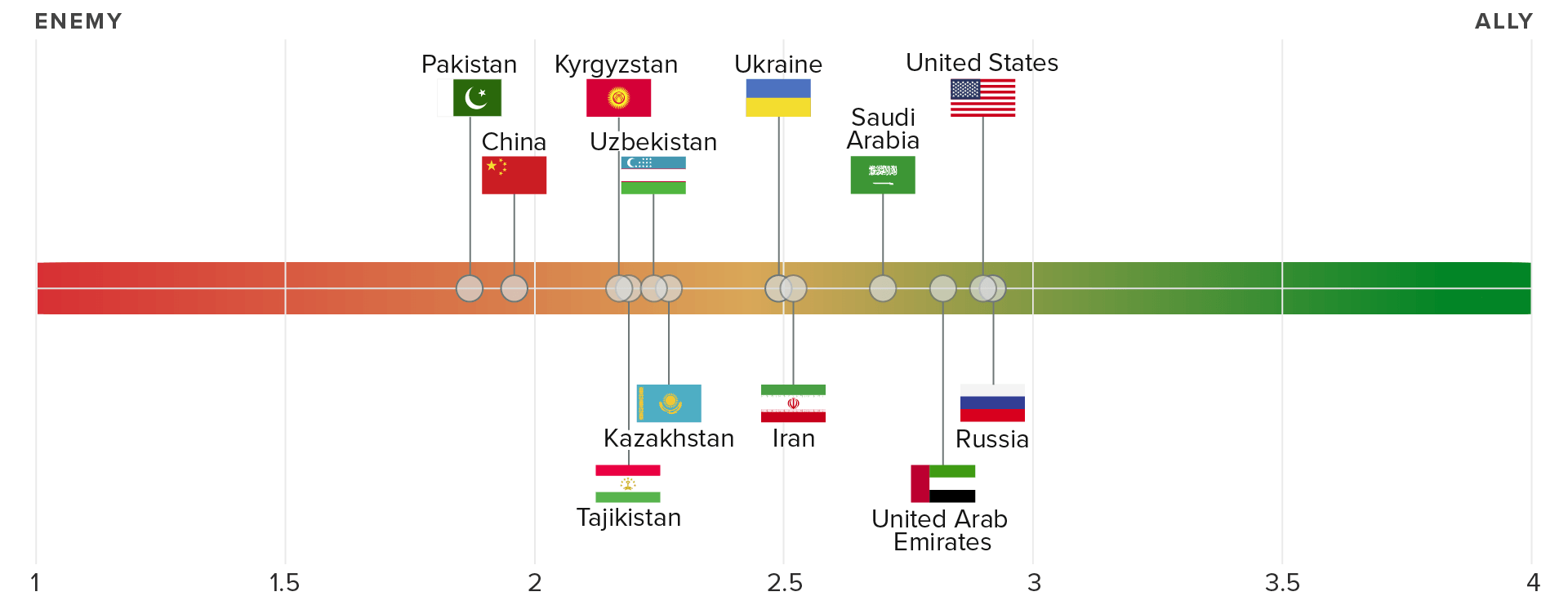

In a clear public nod to these dynamics, Indian adults view Russia as the country most allied to their own, followed closely by the United States, while Pakistan and China anchor the enemy side of the scale. Russia aside, India views the other members of the SCO (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) in a mildly negative light, and several other countries that have historically been more aligned with the United States (e.g., Saudi Arabia) more positively.

Meanwhile, Ukraine and Iran both fall roughly in the middle. Yet Ukraine is a U.S. ally receiving military support in the war against Russia, while Iran has supported Russia’s war efforts against Ukraine. The United States has accordingly sanctioned Iranian weapons manufacturers, and Indian relations with Iran have already led to regulatory issues, further highlighting the risks inherent in India’s attempts to play both sides.

Indians View Pakistan and China as the Least Friendly, Russia and the United States as the Most

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine puts India in a tight spot

India’s highly positive views of both the United States and Russia are particularly striking in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While a plurality of Indian adults (38%) say Russia is to blame for the war in Ukraine, the combined share who blame either the United States (26%) or NATO (18%) exceeds the share who blame Russia by a healthy margin.

More Indians Blame NATO or the United States for the War in Ukraine Than Blame Russia

While the world’s two largest democracies may seem like natural allies, distrust of the United States has become a popular talking point among Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist base. This became especially apparent at the outset of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as Indian commentators took to the airwaves and tabloids to accuse the United States of having instigated the conflict. This false narrative seems to have taken root.

Still, the significant shares of Indians who blame NATO or the United States for the conflict should not be taken as a sign that Indians approve of Russia’s actions. In mid-January before the invasion, net favorability toward Russia among Indian adults was around 30 percentage points higher than net favorability toward NATO, which at the time had similar favorability to the United States. But the former figure plunged closer to parity with NATO after the invasion and has remained there since. Favorability of NATO and the United States, meanwhile, has been much less affected.

Russia’s Popularity Among Indians Plummeted After the Ukraine Invasion but Has Made Up Ground Since

India is behaving pragmatically, not idealistically

As one columnist aptly noted, the current nonaligned movement — a combination of relationships and policies that deliver enhanced security, reliably cheap energy and affordable food imports — is more pragmatic than idealistic. India’s marked reluctance to distance itself from Russia after the invasion of Ukraine reflects this pragmatism.

For one, Russia is an indispensable source of munitions and training, supplying around 90% of India’s military equipment. Even against the backdrop of the invasion, the Indian public narrowly prefers Russia to the United States as a military equipment provider.

Even After Invading Ukraine, Russia Remains India’s Preferred Military Equipment Provider

Russia is also a routine partner in Indian military exercises. As recently as September, the two countries conducted joint exercises, drawing mild criticism from the United States. Still, Indians say the joint drills should continue.

Indians Want Their Government to Continue Purchasing Oil From and Conducting Military Exercises With Russia

Indian adults also express enthusiasm for their country’s decision to buy Russian oil, now selling at a discount on world markets. As global energy prices spiked after Russia invaded Ukraine, India’s minister of petroleum and natural gas argued that, with many Indians living in or on the brink of poverty, the government has a moral duty to source the cheapest energy possible, even if it means filling Russian coffers: Over the past year, Russia jumped from India’s 25th largest trading partner to its seventh largest.

Expect the United States to tacitly accept India’s relationship with Russia because of the need for a regional bulwark against China

The Indian public’s endorsement of continuing business as usual with Russia and its strong support for Modi mean the West should not expect an about-face anytime soon. These dynamics, plus Western (and specifically U.S.-led) efforts to incentivize India to play the role of geopolitical counterweight to China, meanwhile, have led Western leaders to tacitly accept ongoing Russian-Indian military and economic cooperation. Two notable examples on this front are the U.S. Congress’ approval of a CAATSA waiver for sales of Russian S-400 air defense missiles to India last summer, without which India would have been subject to sanctions, and U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s clarification that India could continue to buy as much oil as it wants from Russia, price cap notwithstanding, as long as it avoids G-7 insurance and shipping companies.

Companies should consider India as a friend-shoring destination, but diversification is the safest bet

The likelihood of India abandoning the middle ground — whether in reference to U.S.-Russia or U.S.-China relations — is small. This is good news for global supply chains as long as the West continues to rely on India to counterbalance Chinese influence in Asia. Indeed, even Secretary Yellen has pitched India as an attractive destination for Western companies looking to shift their supply chains out of China amid growing geopolitical tensions.

India is competing with a number of other Asian countries for these investments, including Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia. Multinationals that are more concerned about regulatory risk and basic infrastructure consider India to be less friendly to foreign direct investment than many other Southeast Asian nations. But for companies most worried about manufacturing costs, India’s combination of a highly educated and low-cost workforce is a clear draw.

India’s enormous market, which allows for both domestic sales and internally integrated supply chains, is also an advantage over smaller alternatives in Southeast Asia, as Apple’s expansion of its Indian manufacturing emphasizes. India’s energy opportunism means that in the short term, it is likely to enjoy heavily discounted energy relative to other countries, including China and those in Europe — a potential boon to companies that are able to shift production quickly as the war in Ukraine enters its second year.

While India’s size and economic might make it seem like a credible swap for companies seeking an easy out from China, its professed nonalignment nevertheless poses weaknesses as well. As the West circles its economic wagons, leaning into a form of cooperative isolationism with its closest allies, certain industries risk being hamstrung by India’s peripheral membership in the Western industrial policy clique. In semiconductors, for example, India has ambitions to advance toward the innovation frontier. But it is competing for market share against the United States and the European Union, which in turn are cooperating to synchronize their semiconductor supply chains and deconflict their respective subsidy packages, each exceeding $50 billion.

For supply chains in sectors that aren’t subject to these constraints, India will likely remain an attractive destination. Amid its ongoing border disputes with China and a changing of the guard in the U.S. Congress, companies should nevertheless bear in mind that India is one of many options: Those seeking to diversify their operations regionally should take a lesson from the recent past and avoid putting all their eggs in one national basket (i.e., China) so as to better mitigate their geopolitical risk exposure going forward.

Sonnet Frisbie is the deputy head of political intelligence and leads Morning Consult’s geopolitical risk offering for Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Prior to joining Morning Consult, Sonnet spent over a decade at the U.S. State Department specializing in issues at the intersection of economics, commerce and political risk in Iraq, Central Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. She holds an MPP from the University of Chicago.

Follow her on Twitter @sonnetfrisbie. Interested in connecting with Sonnet to discuss her analysis or for a media engagement or speaking opportunity? Email [email protected].

Scott Moskowitz is senior analyst for the Asia-Pacific region at Morning Consult, where he leads geopolitical analysis of China and broader regional issues. Scott holds a Ph.D. in sociology from Princeton University and has years of experience working in and conducting Mandarin-language research on China, with an emphasis on the politics of economic development and consumerism. Follow him on Twitter @ScottyMoskowitz. Interested in connecting with Scott to discuss his analysis or for a media engagement or speaking opportunity? Email [email protected].