Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine Has Not Increased Global Appetite for a U.S.-China Decoupling

Key Takeaways

The risks of a U.S.-China decoupling loom increasingly large amid the war in Ukraine and Western efforts to lock Russia out of the global economy.

For global multinationals, these risks are material but not a fait accompli.

The United States would need global partners to sustain a decoupling. Yet Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has coincided with a slight shift toward dovish sentiment globally.

This bodes well for multinational supply chains and global capital flows despite persistent strain on U.S.-China relations.

Multinationals should not expect dramatically improved relations anytime soon. But neither should they prepare for an imminent decoupling.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has, if anything, driven a slight decrease in global support for a U.S.-China decoupling

In exceptionally short order, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to a near-complete rupture between Russia and the global economy. It has also caused substantial market turmoil: Food and energy prices are up, and global supply chains are disrupted.

Against this backdrop, the risks of a U.S.-China decoupling loom even larger owing to both sides’ outsize roles in the global economy and China’s reluctance to condemn Russia's invasion of Ukraine, which risks re-energizing hawkish sentiment toward China both in the United States and globally.

For multinationals, these risks are material but not unavoidable. The United States would need global partners to sustain such a decoupling, as is the case with the current coordinated efforts to lock Russia out of the world economy. But our data suggests that global appetite for a U.S.-China decoupling — inferred by examining sentiment surrounding bilateral military conflict and a hypothetical cold war — remains limited in most countries following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and has decreased in others. Though slight and not necessarily causal, this finding bodes well for multinational supply chains and global capital flows despite persistent U.S.-China tensions.

Dovish sentiment on three key fronts

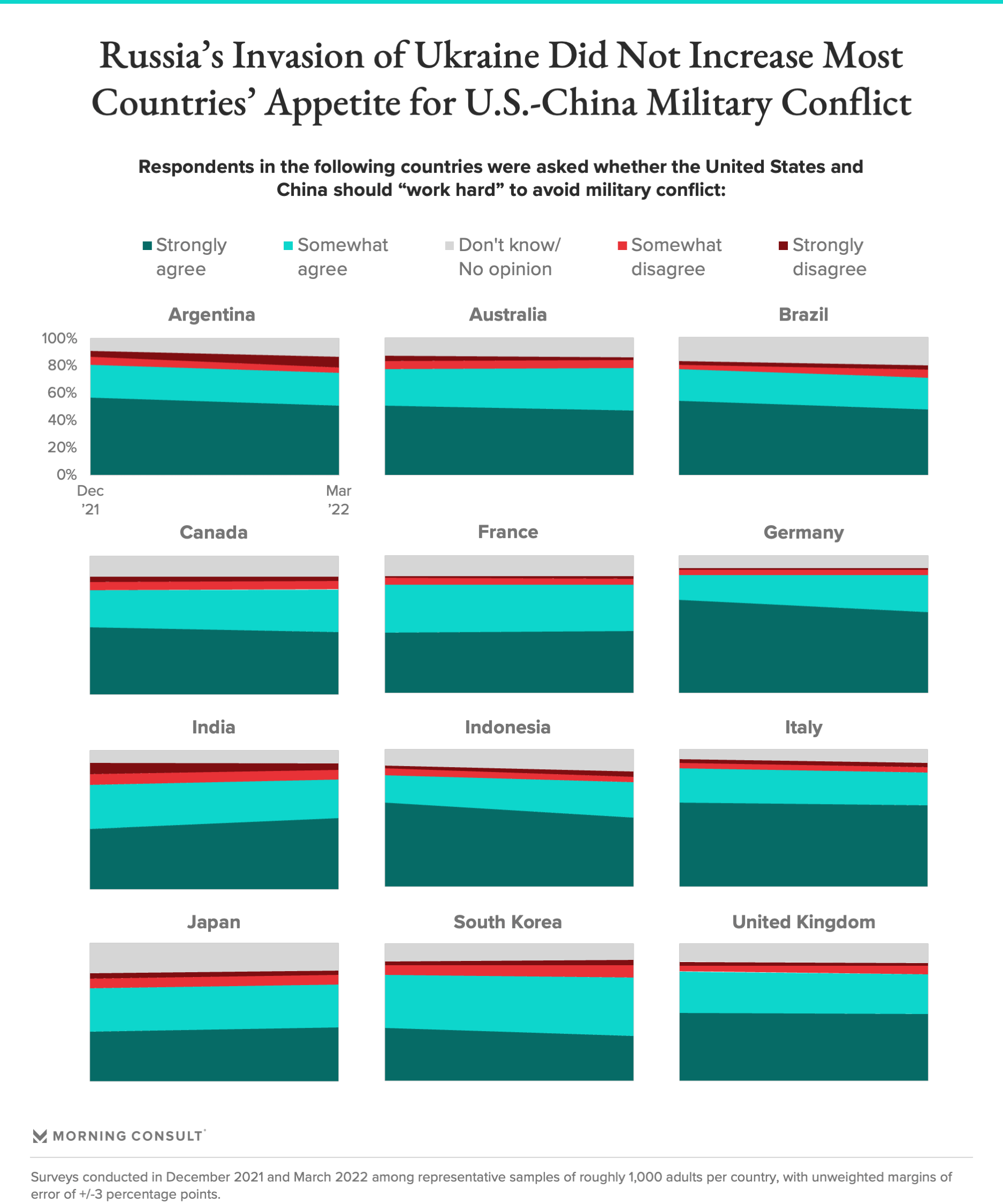

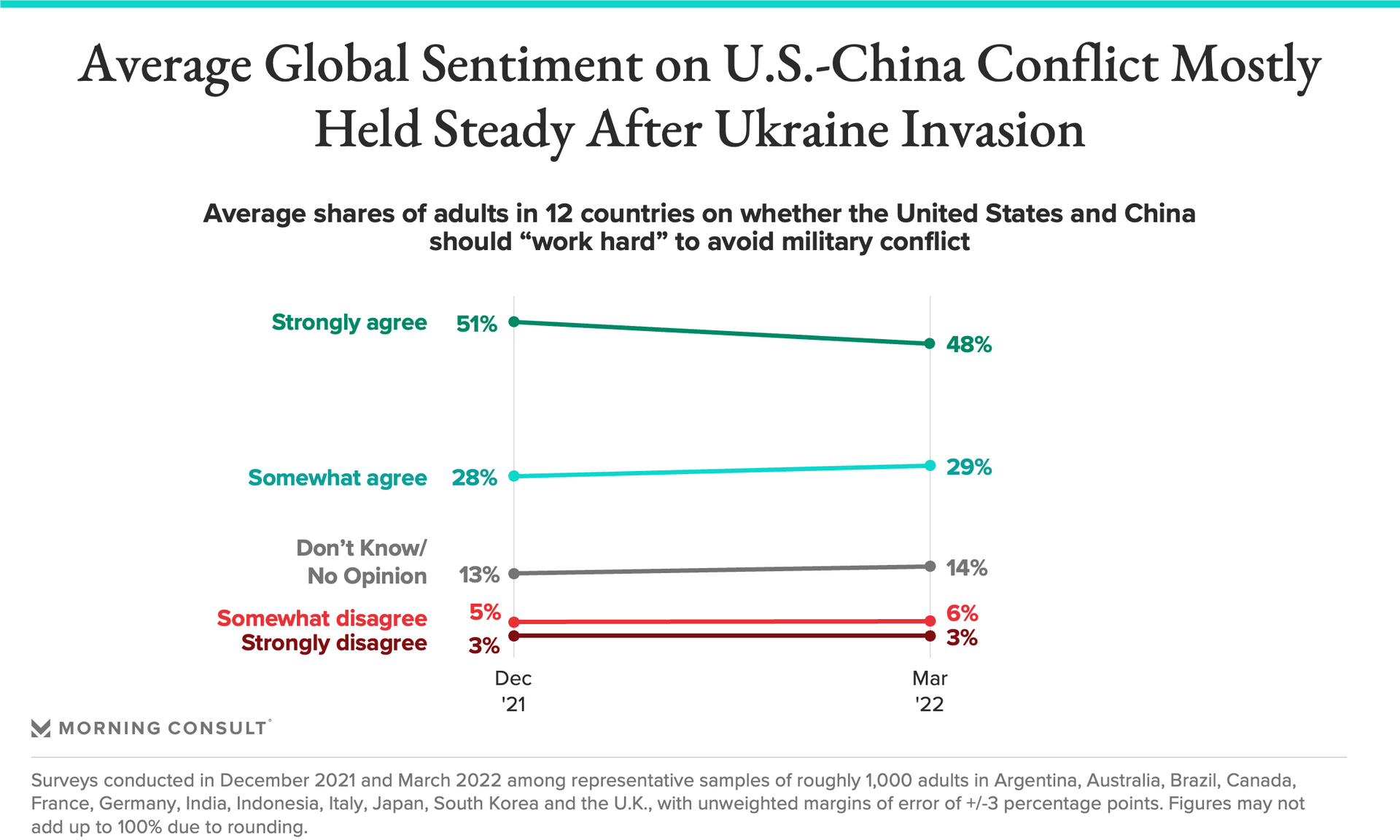

Comparing shifts in sentiment from December 2021 to March 2022 reveals dovish public attitudes toward a U.S.-China decoupling on three main fronts in the period surrounding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24.

First, people in all countries surveyed remain highly averse to military conflict between the United States and China. Across 12 major developed and emerging markets, over two-thirds of respondents in each agree that the United States and China should “work hard” to avoid a military conflict, with a plurality indicating they “strongly agree” in all countries except South Korea.

The average share of global respondents holding the opposite view remained nearly flat over this same period, suggesting that China’s refusal to condemn Russia has not dramatically altered countries’ interest in seeing the United States and China confront each other militarily.

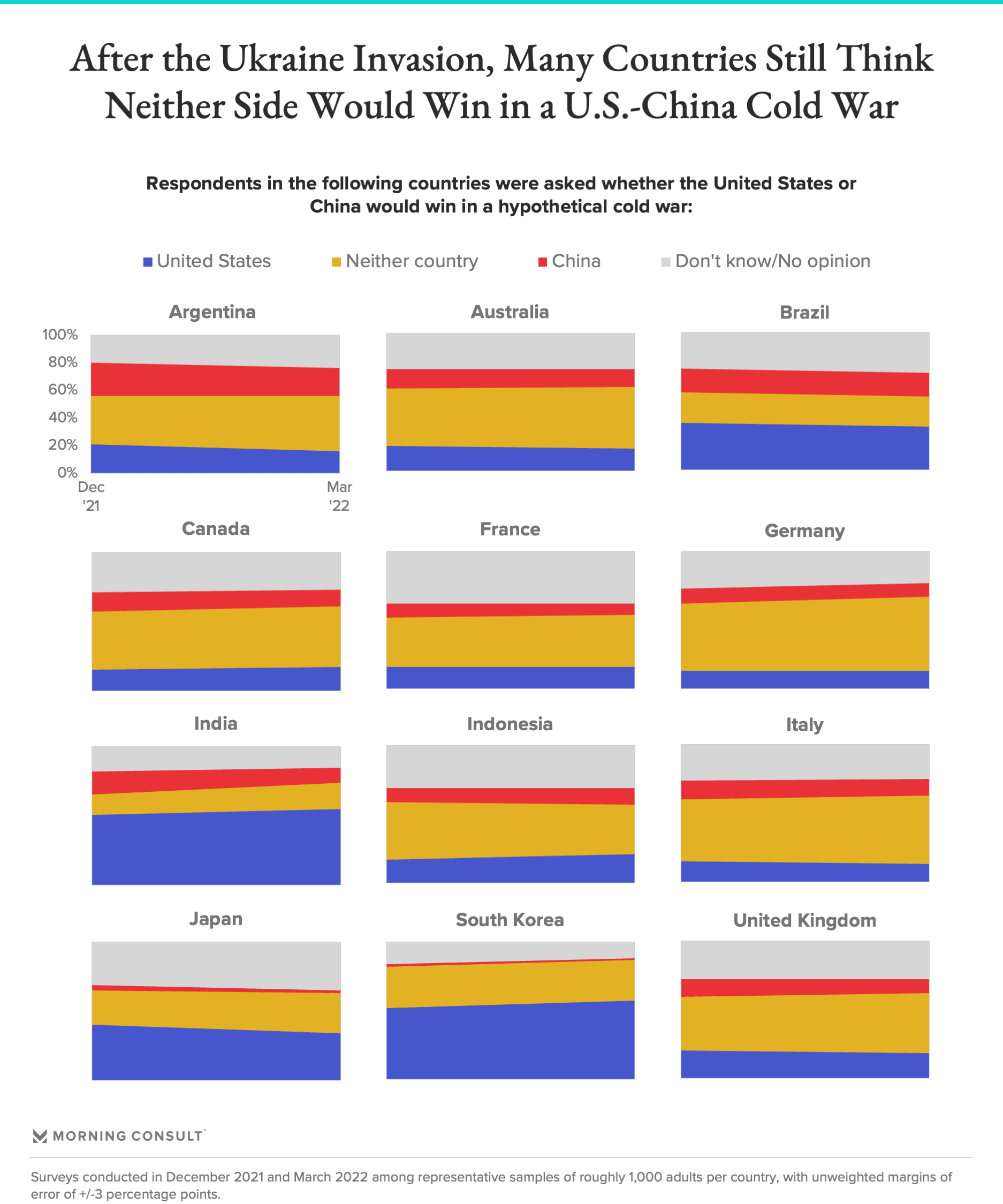

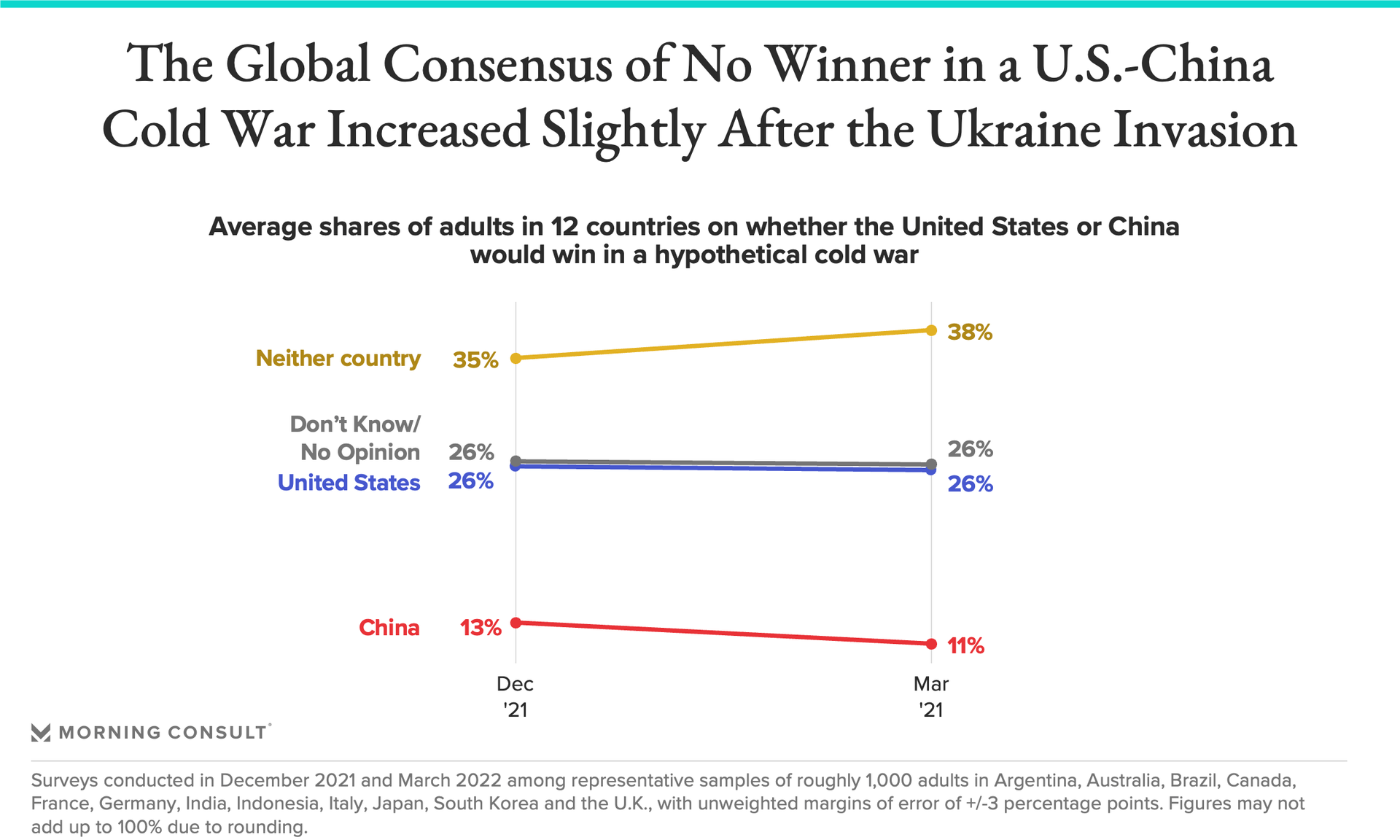

Second, across most of the 12 countries surveyed, pluralities of respondents continue to believe that neither the United States nor China would win in a hypothetical cold war. This finding suggests that Russia’s military setbacks over the past several months — and successful U.S. efforts to support Ukraine’s military — have not convinced global audiences that China would face similar obstacles if it entered into a similar conflict with the United States.

Some evidence of these dynamics is visible at the level of individual countries. The data shows a slight increase in the shares of respondents indicating the United States would win such a conflict in four countries (Canada, India, Indonesia and South Korea) and a slight decrease in the shares saying China would win in 10 countries (everywhere except Brazil and Indonesia).

But in all such cases, the shifts don’t exceed 6 percentage points in either direction. And across all 12 countries surveyed, the average shift in sentiment is more clearly dovish: The share of respondents indicating that neither the United States nor China would win in a cold war ticked up by 3 percentage points.

Moreover, while the average share of respondents who believe that China would win a cold war with the United States decreased by 2 percentage points, the equivalent share indicating the United States would win remained flat, suggesting that declining confidence in China’s likelihood of victory has not translated into greater confidence in the United States’ chances.

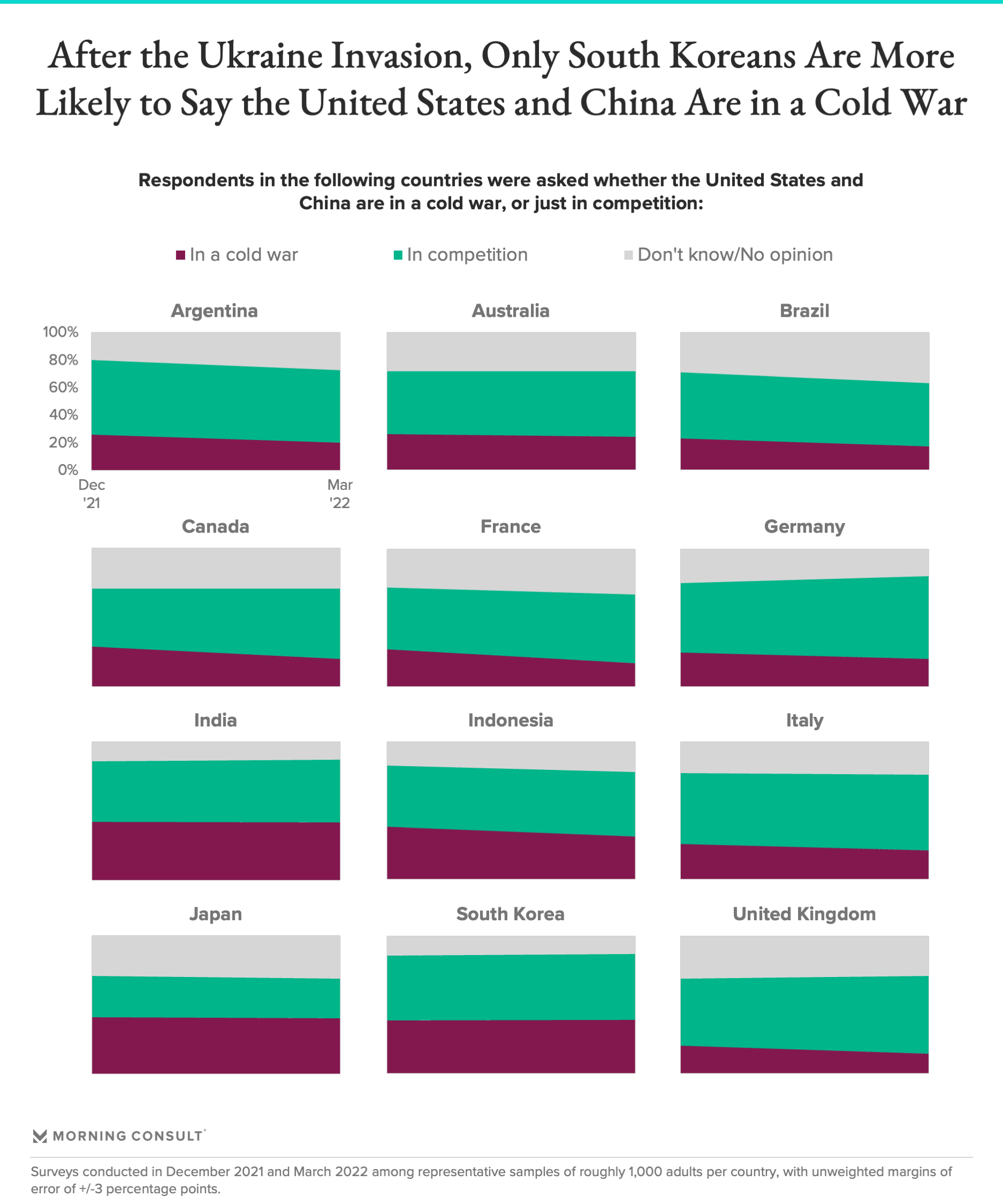

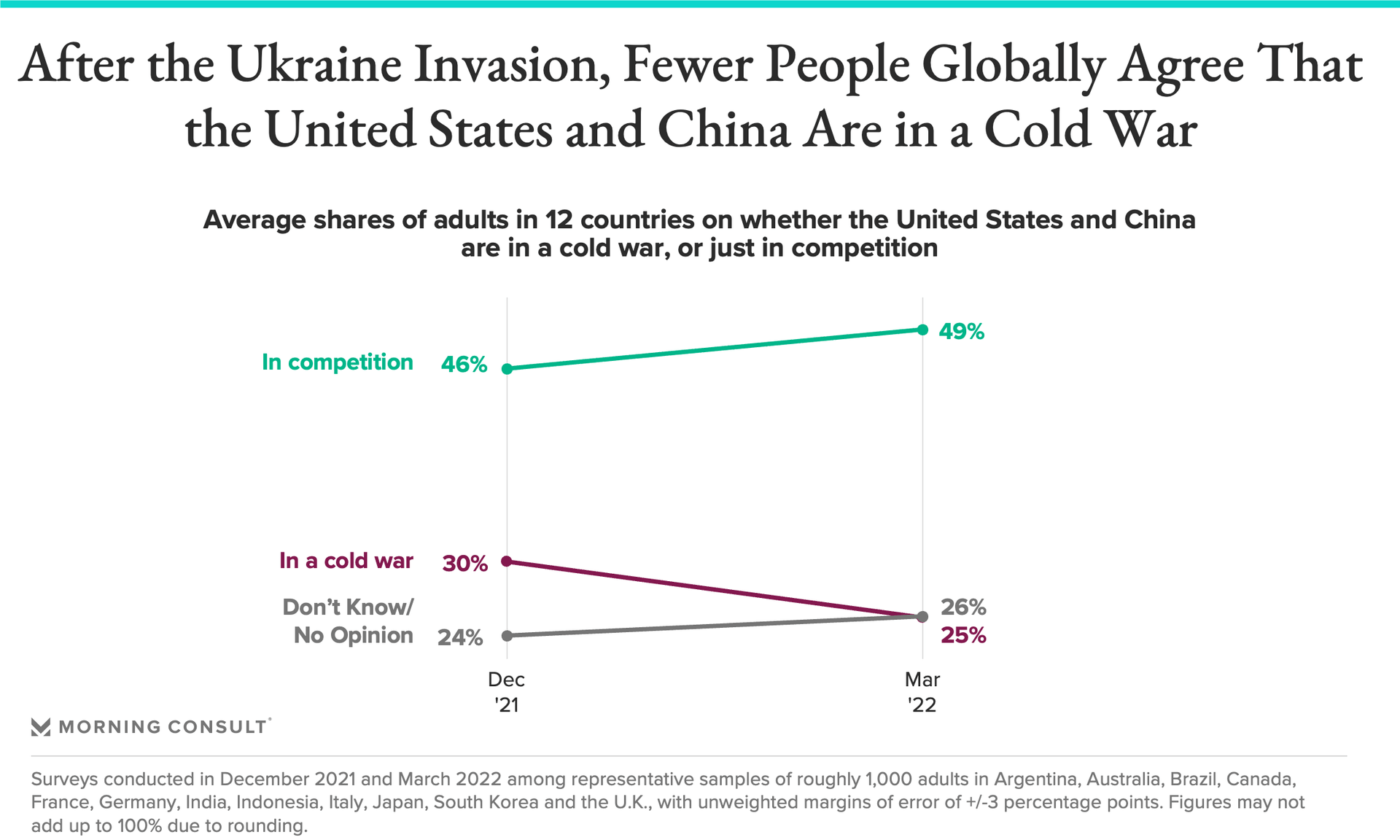

Third, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, pluralities of respondents in all markets except Japan continue to believe that the United States and China are in competition but not in a cold war. And only in South Korea did the share of respondents who believe the two countries are in a cold war increase relative to December. The trend suggests that while talk of China’s “no limits” partnership with Russia in the context of a potential U.S.-Russia cold war has become louder over the past several months, such rhetoric has not yet colored respondents’ views of the trajectory of U.S.-China relations.

This finding is worth emphasizing in light of recent political currents on both sides of the Pacific. Over the past several years, the United States and China have both seen gradual but persistent upswings in hawkish political rhetoric toward each other, apparent in the United States across both the Trump and Biden administrations and in China’s “wolf warrior” diplomacy. To the extent that people globally believe the United States and China are in a cold war, hawkish political leaders in both countries will find it easier to ensure that rhetoric surrounding a hypothetical U.S.-China cold war becomes self-fulfilling. Our data suggests that the politicians and officials who are interested in leveraging rhetoric in this way will face an uphill climb.

Average sentiment across all 12 countries surveyed conveys similarly compelling evidence on this front. The average share of respondents who believe the United States and China are currently in a cold war decreased by 5 percentage points from December 2021 to March 2022. This decline marks the largest average shift in either direction over this period, and suggests that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is more likely to have reduced respondents’ susceptibility to rhetorical U.S.-China fearmongering than not.

Multinationals can be cautiously optimistic

While media discussion of a cold war between the United States and China has diminished slightly since Russia invaded Ukraine, global multinationals are by no means out of the woods. Bilateral tensions have continued to flare over the past several weeks due to ongoing U.S. discussions of potential sanctions against China if it were to offer support to Russia, separate talk of sanctioning Chinese surveillance company Hikvision and renewed efforts to pass legislation geared toward out-competing China.

Persistent bilateral tensions in these and other areas nevertheless mask a high degree of conflict aversion globally, and a trajectory that points ever so slightly in a more dovish direction following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

As our latest report The State of U.S.-China Relations makes clear, multinationals should not expect dramatically improved bilateral relations anytime soon. But neither should they imminently prepare for a U.S.-China decoupling. Respondents in both countries don’t support this, and, on average, neither does anyone else.

Jason I. McMann leads geopolitical risk analysis at Morning Consult. He leverages the company’s high-frequency survey data to advise clients on how to integrate geopolitical risk into their decision-making. Jason previously served as head of analytics at GeoQuant (now part of Fitch Solutions). He holds a Ph.D. from Princeton University’s Politics Department. Follow him on Twitter @jimcmann. Interested in connecting with Jason to discuss his analysis or for a media engagement or speaking opportunity? Email [email protected].