A Gap Between Opioid Bills Has an Easy Fix in Existing Medicaid Waivers, Experts Say

As the House and Senate attempt to reconcile their respective packages of bills addressing the nation’s opioid crisis, the chambers find themselves at an impasse over a provision to lift restrictions on using Medicaid funds for people receiving in-patient treatment for substance use disorders.

But some health experts say the conflict over the provision is unnecessary, not only because states already have ways to fund this care using Medicaid, but because the provision would ultimately do little to combat the opioid crisis.

The House legislation partially repeals the Institutions for Mental Disease exclusion, which currently prohibits the use of Medicaid funds for non-elderly adults in addiction treatment facilities with more than 16 beds. The proposed bill would cover Medicaid beneficiaries receiving treatment for opioid use disorder or cocaine use for up to 30 days. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that a prior version of the House provision would cost $991 million over the 2019-2028 period. The final House bill has not yet been scored.

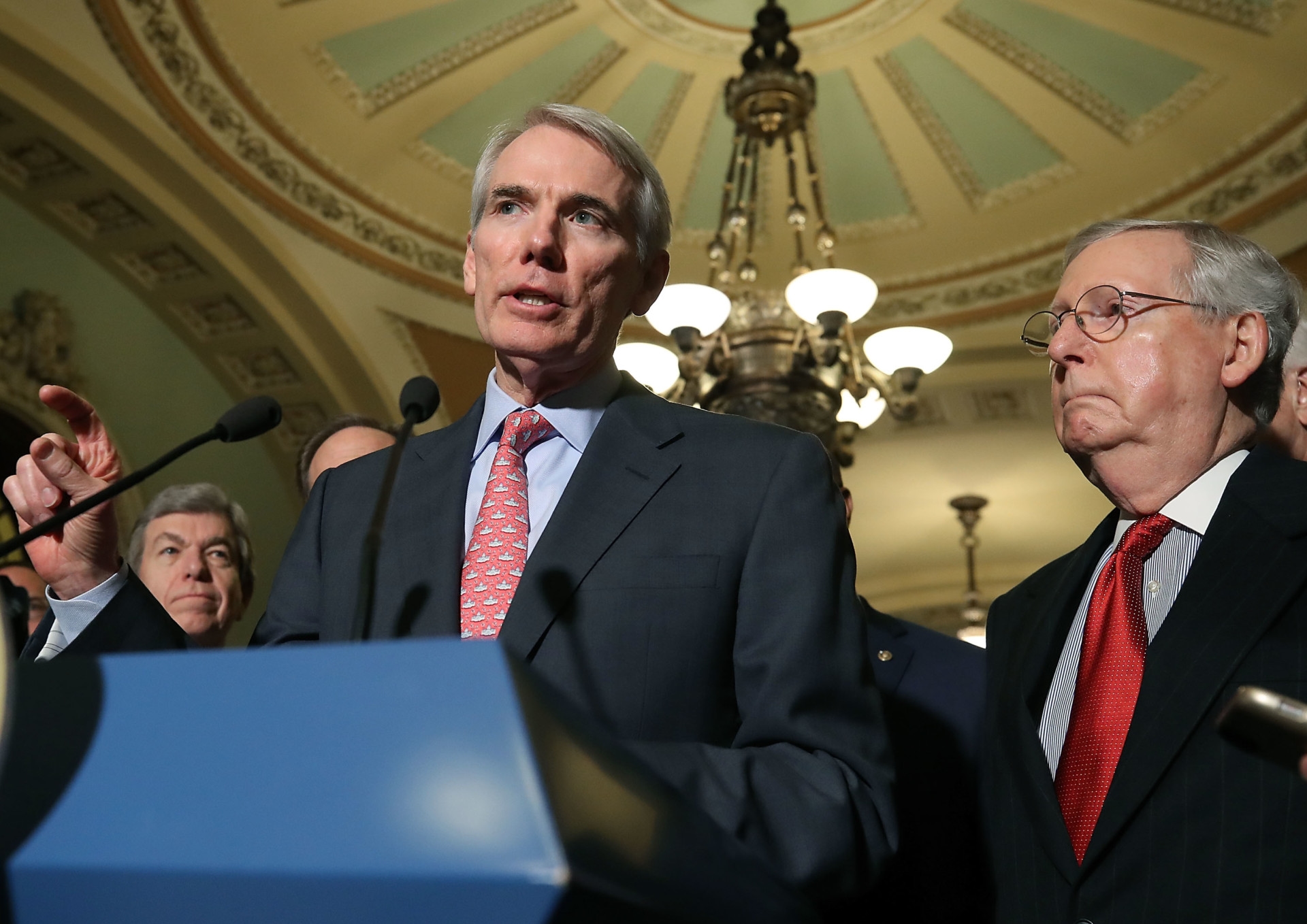

The package passed by the Senate included no such provision, prompting criticism from advocates of expanded addiction treatment and groups such as the American Hospital Association. On Tuesday, Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) introduced legislation to lift the IMD cap entirely, freeing states to use Medicaid funding for coverage at addiction treatment facilities for up to 90 days.

But according to Hannah Katch, a senior policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, states can already apply for waivers to pay for substance use disorder treatment in residential treatment facilities using Medicaid funding. Fifteen states have had waivers approved, and 11 states have requests pending, she said.

“Congress is investing its limited resources in a bill that would allow states to do something they can do today,” she said in a phone interview Monday.

The waivers are derived from Section 1115 of the Social Security Act, which describes the flexibility states have in adjusting certain aspects of Medicaid. States can request these waivers from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to use federal funds in ways not ordinarily permitted.

Katch noted that the Obama administration first released guidance to states about using waivers to offer access to substance use disorder services and that the Trump administration released guidance emphasizing that states can use the waivers for such treatment.

In November 2017, in light of the opioid crisis, CMS issued new guidance describing flexibilities to improve accessibility to substance use disorder treatment through Medicaid Section 1115 waivers.

But Kelly Clark, president of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, said the process of obtaining the Section 1115 waiver is strenuous, time-limited and requires states to consider a number of highly specified pieces.

Repealing the IMD exclusion is a cleaner process that eliminates the need to rely on an administration’s interpretation of a waiver request, she said in a phone interview Wednesday.

Andrey Ostrovsky, who served as chief medical officer at CMS from October 2016 through December 2017 and was involved in the approval process for Section 1115 waivers, said that based on the statute, the extent of the flexibility in waiving certain aspects of the Medicaid law is essentially at the discretion of CMS and Children's Health Insurance Program leadership.

“Depending on the political leadership, that flexibility scope has been interpreted in different ways,” said Ostrovsky, who is now the chief executive of Concerted Care Group, an opioid addiction treatment program based in Maryland.

But, he said, based on the guidance CMS issued, this administration is likely to "green light" states' waiver requests.

Jenny Donohue, spokesperson for Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio), who co-sponsored Portman’s legislation, said Section 1115 waivers take time and are severely limited in scope.

“With more than 11 people dying every day in Ohio we don’t have time for the state to jump through hoops to submit an 1115 waiver and wait an extended amount of time for the waiver to be approved,” Donohue said in an email.

Ostrovsky estimated CMS spends an average of six to 18 months on the process of approving a waiver.

CMS did not respond to a request for comment regarding the application process for Section 1115 waivers.

As the Senate and House enter conference to pen a final package, supporters of the repeal of the IMD exclusion from both chambers appear to be increasingly committed to securing at least a partial repeal.

Charles Daniels, pharmacist-in-chief for the University of California San Diego System, worked with Portman on the legislation to lift the IMD exclusion.

He said he believes the Senate chose to exclude the provision as a matter of expediency, leaving the matter to conference negotiators in the hopes of getting a package passed before the midterm elections.

When asked whether the House would approve a bill that did not include a repeal of the IMD exclusion, a House Energy and Commerce Committee aide said the chamber expects a push to incorporate as much of its provision on the IMD exclusion as possible in the final bill.

But both Katch and Ostrovsky are skeptical of Congress' narrowing in on increased Medicaid funding for addiction treatment centers, be it via Section 1115 waivers or repeal of the IMD exclusion, saying it misrepresents the major drivers propelling the opioid crisis. According to Ostrovsky, the vast majority of opioid-addicted patients are not in an inpatient setting.

“The IMD exclusion is an artifact of time gone by,” Ostrovsky said. Changing it “wouldn’t make much of a dent in the opioid crisis.”

The biggest improvement wouldn’t be increasing funding for inpatient beds, he said, but focusing on Medicaid expansion or increasing access to medication-assisted treatment out in the community, which this legislation has “absolutely not” done.

“This isn’t where the debate needs to be. This is nothing but window dressing,” Ostrovsky said.

But Clark of the American Society for Addiction Medicine contended that the Portman-Durbin bill is a critical piece of the opioids package because the restriction on Medicaid funding poses barriers for people to get treatment.

“My concern is that if the IMD modernization is not a part of the final bill, we will not be set up to make a significant impact on the opioid epidemic,” Clark said.

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated Hannah Katch's stance on the need for legislation to lift the IMD cap.

Clarification: A previous version of this story referred to a Congressional Budget Office estimate for a prior version of a House provision. The CBO has yet to update its estimate for the final version.

Yusra Murad previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.