A Tough Task for FTC: Regulating Instagram When Anyone Can Be an Influencer

Key Takeaways

39% of Instagram users said they were comfortable with accounts on the platform posting ads on their profiles, while 35% said they were not comfortable with the idea.

Roughly one-third said a sample of influencer posts clearly labeled or showcasing a product were not advertisements or that they were unsure or had no opinion.

When Netflix Inc. and Hulu released documentaries in January detailing the fraud behind the Fyre Festival -- which was propelled by glowing posts on Instagram from famous people like Kendall Jenner, Emily Ratajkowski and Bella Hadid -- viewers were outraged by the deception created from posts that lacked details about financial motives. That outrage, however, hasn’t made its way to Washington, where lawmakers and regulators are instead focusing on issues of data privacy, robocalls and competition.

Even though major consumer advocacy groups such as Truth in Advertising have pressed the Federal Trade Commission to crack down on what they see as deceptive advertising, they say that the agency’s lack of adequate resources and rule-making authority, as well as Instagram’s ability to blend sponsored posts seamlessly with regular posts, make it difficult to regulate what influencers are hawking on the platform.

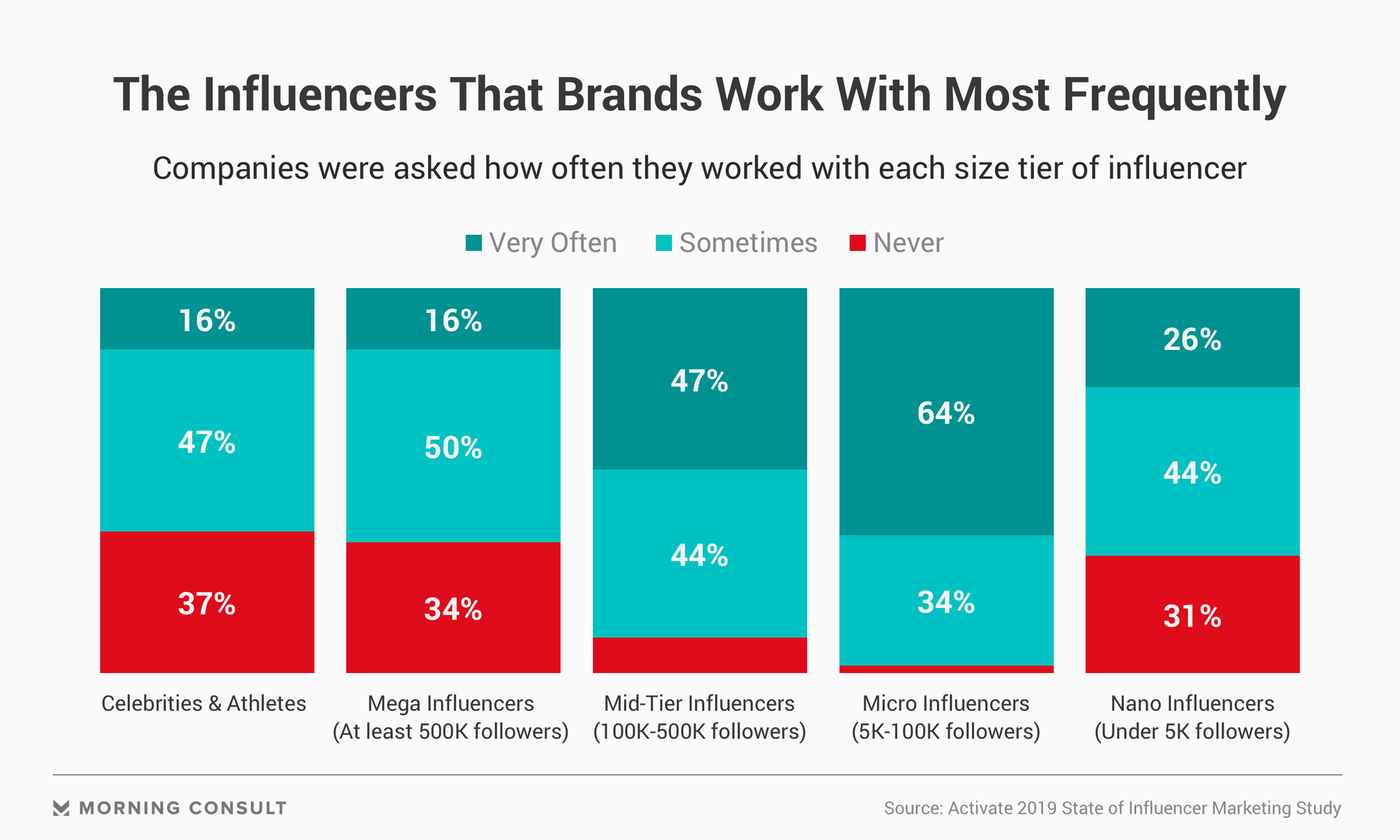

And they say that the regulatory landscape will only get more complicated as more brands work with “micro-influencers,” who have less visibility compared to Jenner and the other Fyre Festival endorsers, and as Instagram begins to roll out in-app shopping tools that enable users to directly purchase items advertised in a post.

Tom Wheeler, who served as chairman of the Federal Communications Commission from 2013 to 2017 and is now a Brookings Institution governance studies visiting fellow, said the agency faces two major challenges in regulating influencer marketing: first, the scope of its jurisdiction, which touches on nearly everything in the economy; and second, the statutes it’s governed by, which limit the regulatory body in both scope and enforcement to the rule-making power afforded to the agency by specific laws.

“It is a daunting challenge for the FTC to try and keep pace with everything” under its jurisdiction, he said. The FTC looking into influencer marketing, he noted, “is therefore nontrivial.”

The potential for consumer harm from misleading advertising on Instagram is highlighted by the Fyre Festival fiasco, whose social media campaign promised a luxury VIP music festival but instead left attendees stranded in the Bahamas with half-built huts and cheese sandwiches.

In the past, the FTC has taken steps to warn influencers to make their payments more transparent. After advocacy group Public Citizen asked the agency in 2017 to investigate specific posts from more than 100 influencers, the FTC embarked on an education campaign, sending a mix of informative and warning letters to more than 90 influencers, including Naomi Campbell, Lindsay Lohan and Nicole “Snooki” Polizzi.

Between May 2017 and December 2018, advocacy group Truth in Advertising investigated more than 1,400 influencer advertisements published from 20 of the 21 influencers who received official warning letters and found that not one example met the standards laid out by the regulatory agency, with some missing disclosures altogether and others not providing adequate sponsorship labels.

No further public actions on the issue have been taken by the FTC since 2017. Truth in Advertising filed a complaint with the FTC in March, and Public Citizen said in an interview that it is continuing to pursue greater enforcement actions from the agency.

Wheeler said the main drivers for FTC investigations are complaints filed by consumers and advocacy groups, research by the agency’s staff and pressure from Congress. But even after the release of the Fyre Festival documentaries, Morning Consult data suggests Instagram users aren’t likely to sound the alarm on influencer posts.

In one survey conducted Feb. 14-21 among 2,150 current and recent Instagram users, respondents were almost evenly split on their comfort with influencer marketing on the platform, with 39 percent saying they were comfortable with accounts on Instagram posting ads on their profiles compared to 35 percent who said they were not comfortable with the idea.

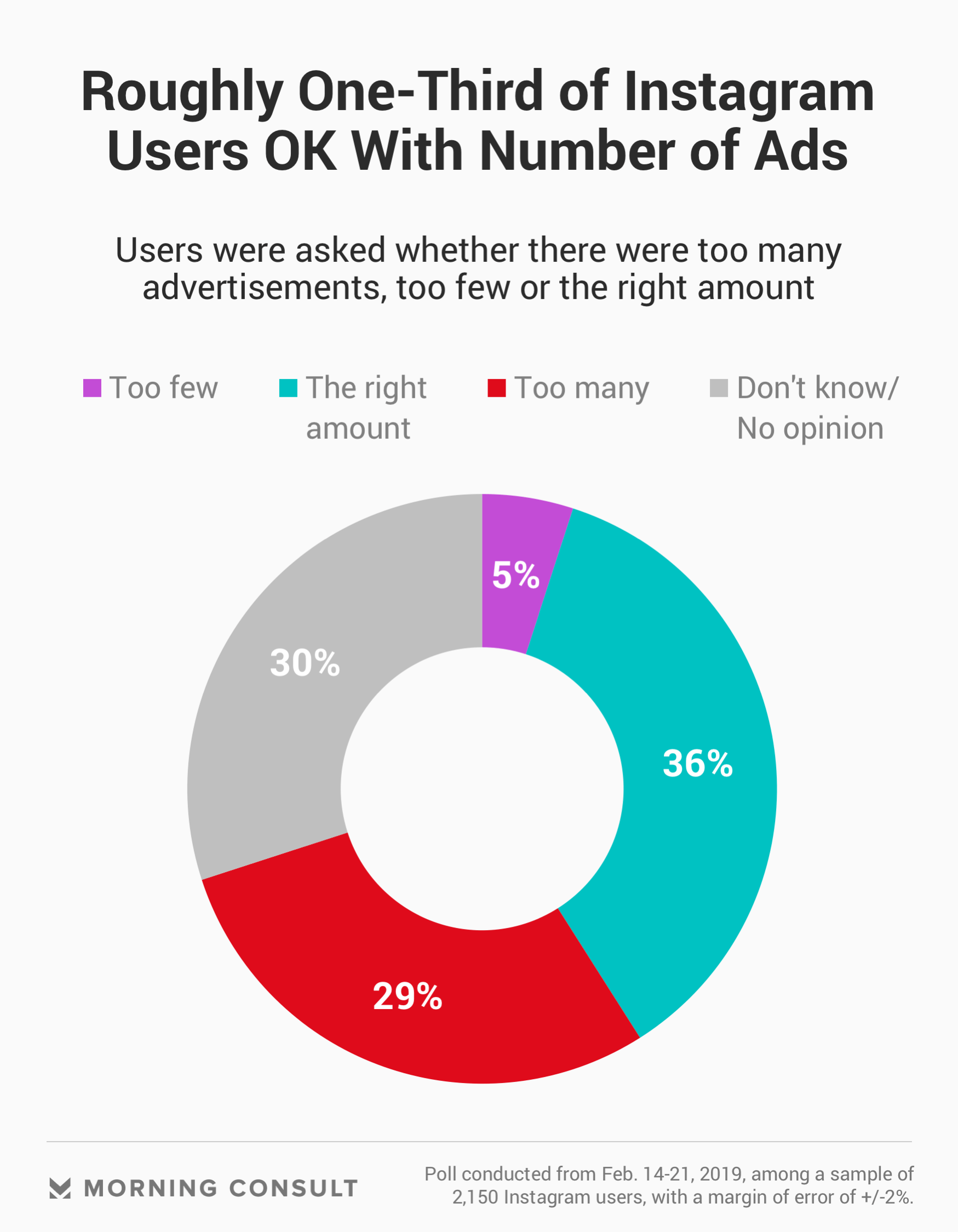

At the same time, a plurality (36 percent) said the site has the “right amount” of advertisements, compared to 29 percent who said there are “too many.”

But, as advertising experts are keen to point out, the design of influencer advertisements on Instagram makes them easy to blend into the sea of ordinary user posts -- whether they disclose them or not.

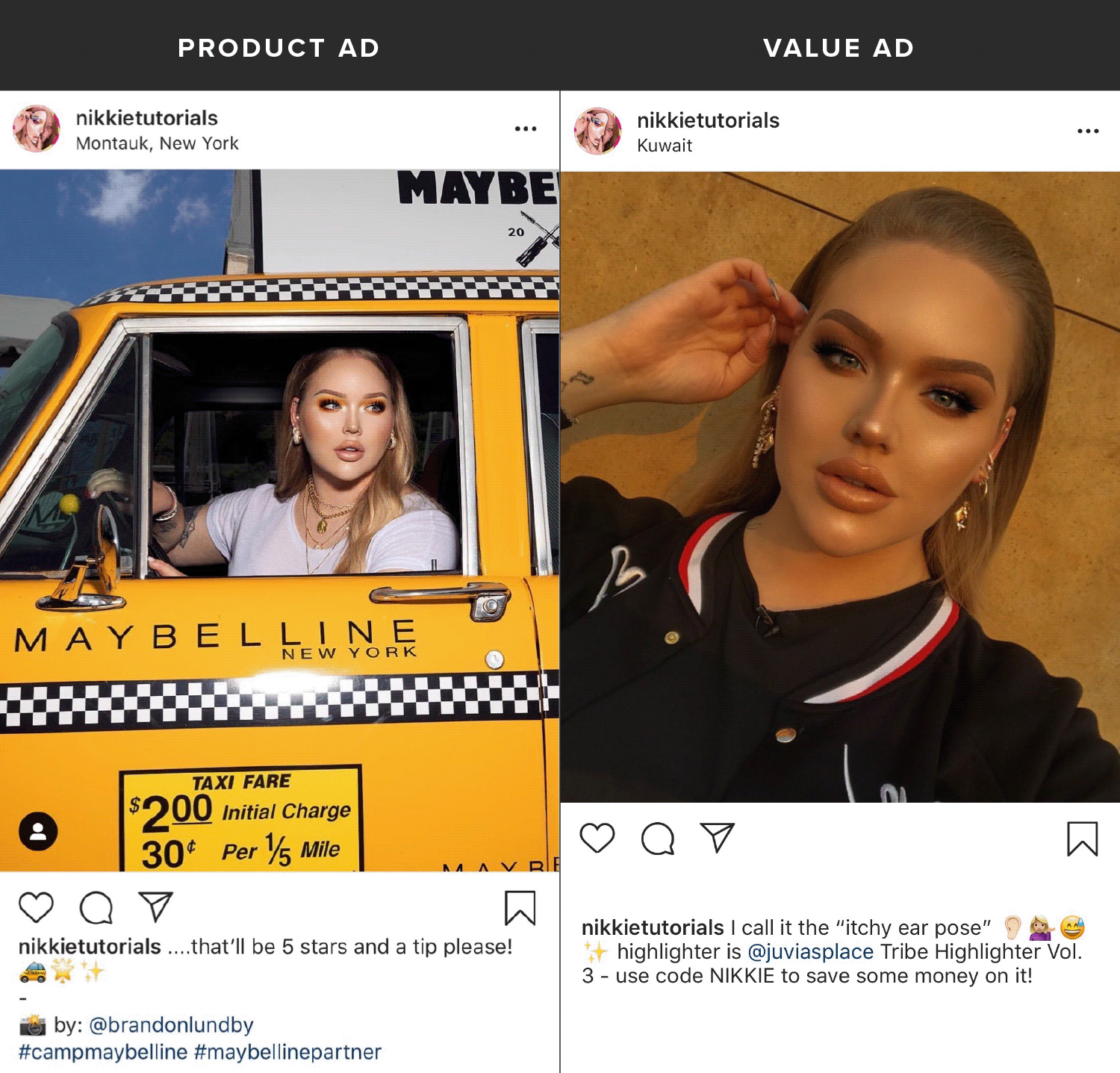

A second Morning Consult survey conducted at the same time as the earlier-mentioned poll among 2,230 current and recent Instagram users tested 12 real-life examples of influencer ads, clearly labeled according to the FTC’s guidelines or prominently showcasing a product, from six accounts that span the travel, beauty, fashion and lifestyle, parenting, entertainment and food worlds. The survey also tested two types of advertisements from each account: one product-based ad that clearly featured the product in mind, such as a credit card or makeup product; and another that advertised a value, such as posts for insurance sponsorships.

Most people (an average of 67 percent), were able to identify the posts as ads, but a third on average did not: Approximately 21 percent said they weren’t ads and another 12 percent said they didn’t know or had no opinion.

In the first Morning Consult survey of 2,150 Instagram users, people seemed to favor industry self-regulation over government intervention: Sixty-two percent said influencers should clearly disclose when they are being paid to post, but 41 percent said the government should not get involved in regulating such ads. A third favored government regulation, while 26 percent had no opinion.

Public Citizen and Truth in Advertising say the issue of influencers’ lack of disclosures on advertisements and sponsored posts has reached a level where tougher, more resource-intensive enforcement actions should be used more often, especially as Instagram expands tools to allow influencers to sell a brand’s merchandise through their posts.

Kristen Strader, campaign coordinator for Public Citizen’s Commercial Alert program targeting deceptive commercial practices, said Instagram users already have a difficult time consciously distinguishing advertisements from the average user’s content, so adding e-commerce tools to influencer posts only exacerbates the problem.

“People don't consciously think that ‘With every like and scroll I make Instagram is building an advertising profile on who I am and manipulating me into wanting products,’” Strader said. “But when it comes to transforming Instagram into an e-commerce application intentionally, which it sounds like Instagram wants to do, that creates an even bigger divide between user expectation and reality -- and that's concerning.”

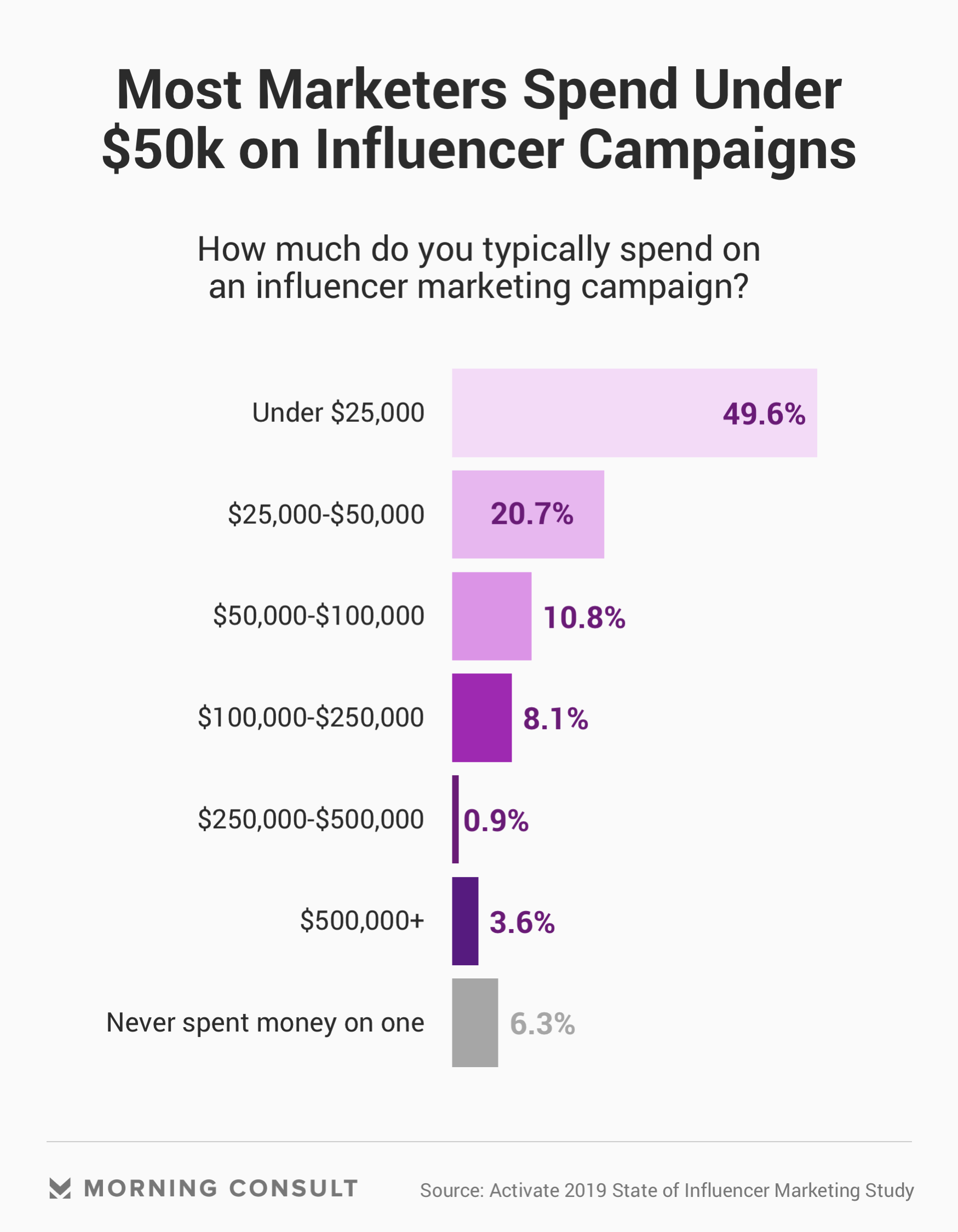

The Facebook Inc.-owned photo and video sharing platform is a hotbed for influencer marketing, which could become a $6.5 billion business across all advertising outlets this year, according to Influencer Marketing Hub’s 2019 marketing survey of 800 marketing agencies, brands and other relevant professionals. (Facebook did not respond to a request for comment.)

Sunil Wattal, associate professor at Temple University’s Fox School of Business focused on tech adoption and internet marketing, said this marketing strategy is valuable to advertisers because influencers, especially micro-influencers, who are defined as users with 5,000 to 100,000 followers, are viewed as quasi-friends to the users who follow them. Because of the relative low barrier to entry to become an influencer, Wattal said it wouldn’t be surprising if regulation -- whether it be industry self-regulation or government oversight -- comes down the pipeline.

“It is a new Wild West for digital marketing in the sense that there’s very few rules or guidelines,” he said. “You can see a lot of problems happening around this kind of marketing.”

Strader said the lack of disclosures from smaller influencers is more deceptive than when a celebrity opts not to disclose a payment because users tend to expect influencers such as the Kardashians or rapper Cardi B to be paid to post.

In an email, an FTC spokesperson said the agency does not define influencers by the number of followers they have, noting that anyone who posts content as a product endorsement must adhere to agency guidelines for sponsored content. It declined to answer questions about the agency’s current investigations, current regulatory strategy or what it plans are in the future.

Strader said Public Citizen is continuing to push for tougher actions from the FTC and for lawmakers to take up the issue -- especially following the Fyre Festival -- but her group is focusing more of its advocacy work on comprehensive privacy legislation.

Bonnie Patten, executive director of Truth in Advertising, said her group would love to see more enforcement actions that result in fines for influencers and the companies that pay them; however, she says with the agency’s current lack of resources, that might not be possible.

But she noted that Truth in Advertising is meeting with regulators and lawmakers to push for tougher restrictions because the FTC can’t do it alone.

“It's just such a large number of companies and influencers now that are ignoring the law, and I don’t see that the FTC has the resources to really manage that,” she said.

This story has been updated to include Facebook's lack of response to a request for comment.

Sam Sabin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering tech.