As COVID-19 Takes Toll on Mental Health, Providers Push to Increase Workforce and Access Beyond the Pandemic

Key Takeaways

About 2 in 5 adults are suffering from symptoms of anxiety and depression, CDC data shows.

Behavioral health providers say they need more support to shore up their workforces and meet demand for services.

Members of Congress say they plan to introduce mental health legislation this year to combat the COVID-19 pandemic’s ripple effects.

Last summer, as news reports tallying the sick, the dead and the destitute became the soundtrack of daily life in the United States, Dr. Peggy Terhune began to worry about how the COVID-19 pandemic would reverberate in the American psyche, including long after the imminent threat of the virus fades.

“The entire nation is experiencing PTSD,” said Terhune, chief executive of Monarch, a behavioral health provider that treats some 30,000 patients across North Carolina. What’s more, she said, the country’s existing workforce is unequipped to meet the impending wave of people in need of mental health treatment.

Now, providers and advocates hope policymakers will move with a sense of urgency to shore up the country’s mental health workforce and expand access to this type of care in both the short and long term -- and say such a focus is critical as lawmakers seek to help the country recover from the pandemic.

The toll of the pandemic, one year in, is beginning to crystalize. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, some 2 in 5 adults are suffering symptoms of anxiety or depression, while drug overdose deaths hit a record high last spring.

Many people are seeking mental health treatment for the first time. And pediatricians are spending less time treating children for respiratory illnesses and more on their mental health concerns.

“I don't think just going back to the way that it was, where there was one place that everyone needed to go for mental health, is going to really hold muster post-COVID,” said Dr. Benjamin Miller, chief strategy officer of Well Being Trust, a foundation that takes a community-based view of mental health. “We've got to be able to be more nimble.”

Telehealth, for example, has been a boon for mental health providers, with behavioral health visits hundreds of times higher during several months of 2020 than a year earlier, according to an analysis from Well Being Trust and the consulting firm Milliman.

Digital medicine isn’t a silver-bullet solution, though, given some people still struggle to access it and some commercial payers have already begun rolling back the telehealth services they’ll cover, said Verna Foust, CEO of Red Rock Behavioral Health Services in Oklahoma.

That means some patients whose insurance will currently pay for mental health treatment via telehealth may not have the option in the future, even if federal policymakers extend the flexibilities they granted last year to make telehealth more accessible. Lack of insurance coverage for these services could quickly become “a huge barrier for people,” Foust said.

The more long-term challenge, though, is that the corps of mental health professionals can’t meet the demand for their care. Roughly 12 percent of the U.S. population needed mental health care recently but didn’t get it, according to federal estimates, and many organizations had to cancel, reschedule or turn away patients altogether this winter.

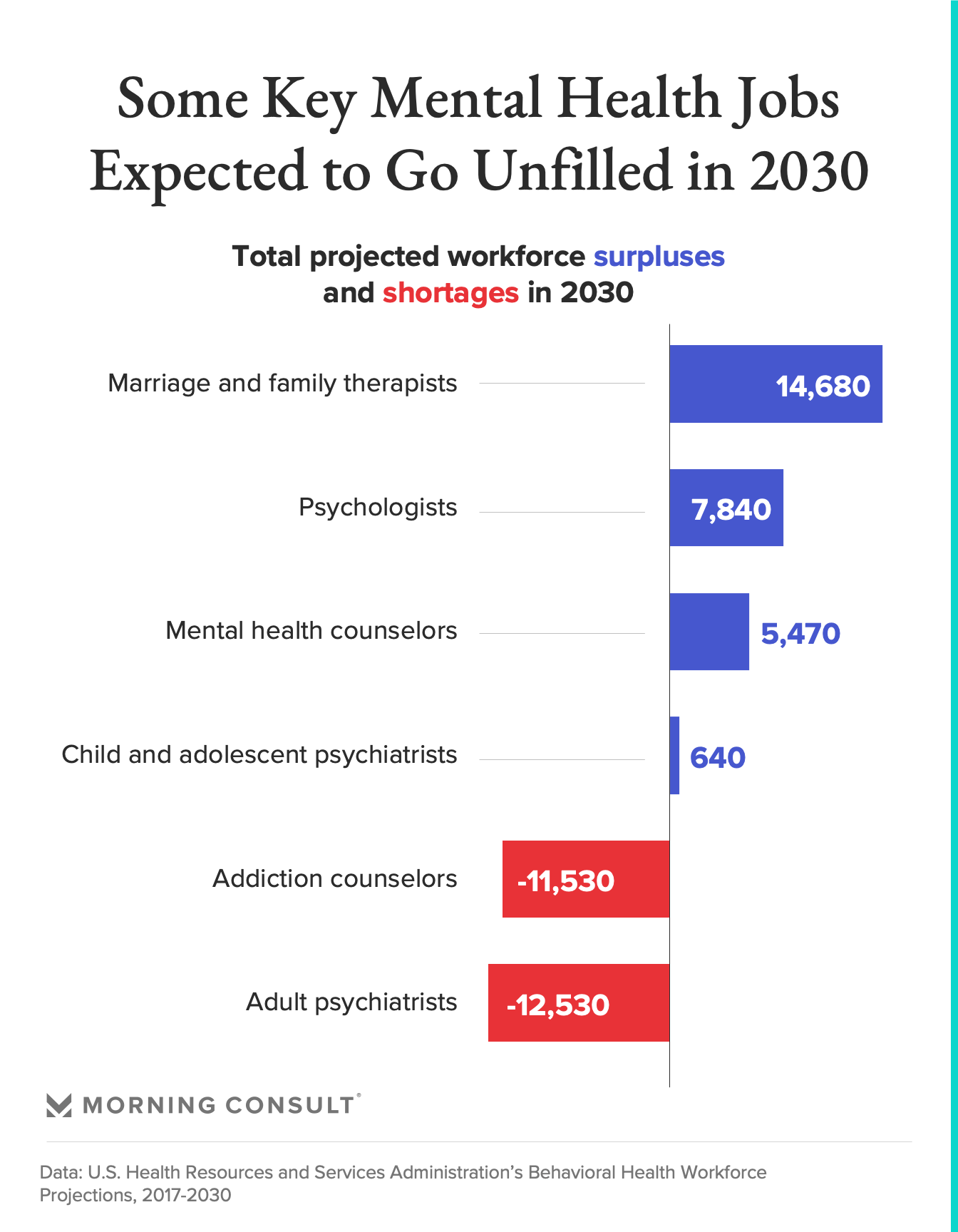

Even before the pandemic, the country lacked enough clinicians to treat behavioral health problems ranging from mild anxiety to severe addiction, and there’s an expected shortfall of adult psychiatrists and addiction counselors by 2030. Foust said the shortfall is partially due to low pay.

Providers and advocates said integrating a broader range of professionals, such as family and marriage counselors as well as peer support specialists, into the reimbursable mental health workforce would go a long way toward closing that gap. The idea is gaining traction: In January, Rep. Mike Thompson (D-Calif.) introduced a bill with 13 bipartisan cosponsors that would cover family therapy services under Medicare.

“In this arena, we don't have a workforce shortage -- we have workforce underutilization,” said Dr. Gray Otis, a mental health counselor who runs a private practice in Utah.

Miller, meanwhile, is supportive of taking a more holistic approach to mental health, one that better integrates behavioral health and primary care services, leans on community health workers and provides more clinicians with training on mental health issues and addiction, not just specialists.

“We need to be training clinicians for this new system that we want, not the system that we have,” Miller said.

The Biden administration and Congress have taken some other steps to address these challenges. Earlier this month, the White House announced $2.5 billion in funding to address mental health and substance use disorders, including $825 million in state grants for community services that address gaps in treatment, like emergency phone lines and mobile crisis teams that can be quickly deployed.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which allocates the grants, is pushing states to “think seriously about building out crisis services and increasing the responsiveness of their services,” said Dr. Anita Everett, director of the agency’s Center for Mental Health Services.

Beyond one-time grants, though, providers need sustained funding, said Dr. Brian Hepburn, executive director of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors.

On a broader level, House lawmakers are also restructuring their focus on addiction to include a more comprehensive behavioral health portfolio, Roll Call reported, with plans to introduce additional legislation addressing mental health at some point this year. At a briefing with reporters earlier this month, Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.), who sits on the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, said he would “fight hard” to ensure support for the mental health workforce is included in a future bill.

There’s also momentum at the state level. In Tennessee, for example, behavioral health providers are pushing the legislature for a 4 percent increase in Medicaid reimbursement for their services so they can raise wages for the workforce, said Jerry Vagnier, CEO of the McNabb Center, which sees some 31,000 patients across 29 counties annually. Providers are also asking the state for additional telehealth flexibilities and to encourage private insurers to continue offering coverage for tele-mental health care.

“We find a lot of verbal support for what we're trying to accomplish, but it hasn't moved through committees yet,” Vagnier said.

Providers and advocates across the country say time will tell whether lawmakers make good on their promises to address the pandemic’s mental health toll. A bipartisan bill introduced Thursday, for example, would make a broader range of professional training programs eligible for federal Pell grants, including multiple health care roles. Notably, none of those jobs target mental health.

And even as legislation comes together, the country’s mental health landscape is evolving. In North Carolina, for example, Terhune said demand for services “roared up” again in January and February, while Vagnier is expecting a “surge” in the coming months.

“Progress is sometimes enhanced by crisis,” Hepburn said.

Gaby Galvin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.