Energy

DOE Program’s $3.7 Billion Loan Highlights Lack of Action on Other $40 Billion It Holds

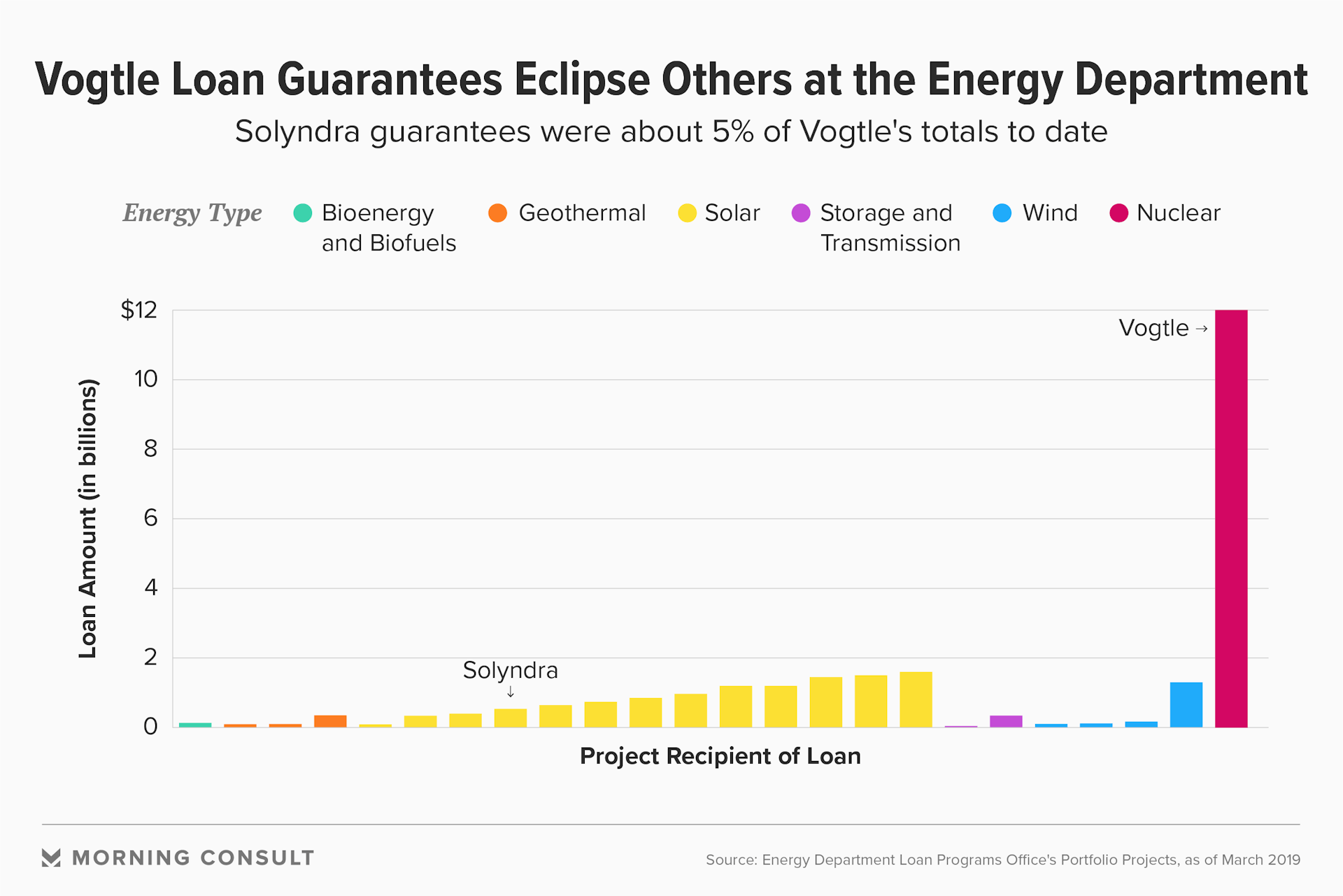

The Energy Department’s announcement on March 22 that it had granted the over-budget Vogtle nuclear power plant expansion project in Georgia a loan guarantee of $3.7 billion was notable not only for adding to the program’s existing billions in guarantees for the project, but also for having been issued by the department at all.

The lack of action from the loan financing program comes at a time when the administration and Congress want the United States to remain competitive in energy innovation and when energy companies are said to have a continued interest in accessing the program’s financing. Currently, the Energy Department under President Donald Trump still sits on about $40 billion that it could be using to assume the debt obligations of privately financed various energy projects, from renewable and efficiency projects to fossil and nuclear energy ventures.

Peter Davidson, chief executive and co-founder of climate and energy investment firm Aligned Intermediary Inc., who served as executive director of the Loan Programs Office between 2013 and 2015, said he has spoken with industry participants still interested in securing loans and committing capital.

Meanwhile, the range of technology needs that the program could help, from carbon capture to energy storage and advanced renewables, is expanding, said Dan Reicher, an assistant secretary of energy for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy at the department from 1997-2001.

The program also maintains the support of lawmakers who want to see the Energy Department take a prominent role in energy innovation. On Friday, six Democratic senators; Republicans Bill Cassidy of Louisiana and Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia; and Independent Angus King of Maine pressed Senate appropriators by letter to secure full funding for the Title 17 Innovative Energy Loan Guarantee Program run by the office in order to “help provide meaningful solutions to our nation’s energy challenges.”

Davidson said it is a shame that the office has not issued loans outside of Vogtle, whose $3.7 billion guarantee was in addition to other such guarantees during the Obama administration, bringing its total guarantees to $12 billion. The guarantee is sizeable for the financing that the Loan Program Office has announced to date, but commensurate perhaps with the size and risk of reactor construction.

A staffer on the House Science, Space and Technology Committee Democratic majority said it makes no sense that the administration has determined that the loan guarantee program is both critical to the nuclear industry’s future and will never have any utility for anything else.

An Energy Department spokeswoman said by email Wednesday that such large-scale projects “typically have long timelines” and that the approval process depends on current market trends and needs. The spokeswoman declined to provide any information on the applications it has received, saying they are “business-sensitive information.”

The Trump administration may be acting to keep the Vogtle project alive so that taxpayers are not responsible for the earlier $8.3 billion in guarantees, said Katie Tubb, senior policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation.

“They’re on the hook,” she said. “Maybe they’ve saved Vogtle. They’ve certainly staved off a political nightmare” of a potential folding of the project, she added.

But Davidson, who recommended that then-Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz sign off on the first Vogtle guarantee, said the Vogtle loan has been a “good loan” from a banker’s perspective and from that of the agency. While the project is over budget, the loan is secure and being repaid, he said.

Given the increased safety and efficiency of the AP1000 reactors being built under the project and the willingness of a utility to get rate-based approval to fund it, “it was certainly something that was important for the federal government to support” and would not be deployed at the Vogtle site without the Loan Program Office, Davidson said.

While the United States must determine whether to pursue nuclear power in light of significant cost overruns related to permitting, labor quality and who ultimately pays for ballooning costs, those questions are outside of the Loan Program Office’s purview, said Davidson.

The program has experienced a pause in new disbursements before. While the Loan Program Office’s ability to make loan guarantees for new energy technologies was born out of the bipartisan 2005 Energy Policy Act, it fell victim to partisan disagreements over whether the office’s programs should exist -- especially with the collapse of loan recipient Solyndra LLC.

The matter contributed to a suspension in new loans issued under the program in President Barack Obama’s second term in office, as did the departure of the office’s former Executive Director Jonathan Silver at the end of Obama’s first term and the conclusion of a project deadline for when renewable energy projects had to end under a stimulus package, Davidson said.

Even during the Obama administration, there was a period with concern about the political or actual risk of issuing further loan guarantees, said the House Science staffer.

Opponents of the program say the initiative lends itself to cronyism and risky spending of tax dollars, said Tubb, who said the private sector should be left to this kind of financing. “The motivations are very different if you’re spending other people’s money” for political ends, she said.

Across each of its three budget requests, the Trump administration has requested that Congress scrap the office’s two loan programs -- the Title 17 program and the Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loan Program -- and have the office simply monitor its existing portfolio of projects.

Currently, 20 companies have active loans and loan guarantees with the office, according to the office’s portfolio of projects. The program has realized about 3.1 percent in losses out of its total disbursement while receiving $2.52 billion on interest as of December 2018, according to the agency. That compares with the 0.95 percent nonperforming loans ratio in the United States at the end of 2018, according to Federal Reserve data.

Any money that the office currently makes off its loans goes back to the Treasury, rather than back to the office to fund more projects, which Reicher, who is founding executive director of the Steyer-Taylor Center for Energy Policy and Finance at Stanford University, said is “a major problem” with the program.

Although the Loan Programs Office’s loan-making authority will end after it runs out of its remaining funds for such a purpose, lawmakers have previously considered creating a more permanent, self-sustaining energy loan-making authority in the federal government.

In 2011, the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee discussed the idea of creating a Clean Energy Deployment Administration, a federal program that would be able to generate profits through its loans, guarantees and other investments, similar to the way the U.S. Export-Import Bank can self-sustain through its operations. But the effort was opposed by groups that advocate for a limited government, including the Competitive Enterprise Institute, and the bill stalled.

It’s worth taking another look at such an authority now, said Reicher, amid bipartisan interest in fostering energy technology and innovation.

The House Science committee staffer said the idea of a Clean Energy Deployment Administration is worthy of further discussion, though the committee would first need to see the details of any such proposal.

A spokeswoman for Senate Energy and Natural Resources Chairman Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) did not respond to an inquiry on whether the senator is interested in legislation for such a program.

Jacqueline Toth previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering energy and climate change.