Energy

EPA Science Transparency Rule Faces Two Potential Paths to Revocation in Biden Administration

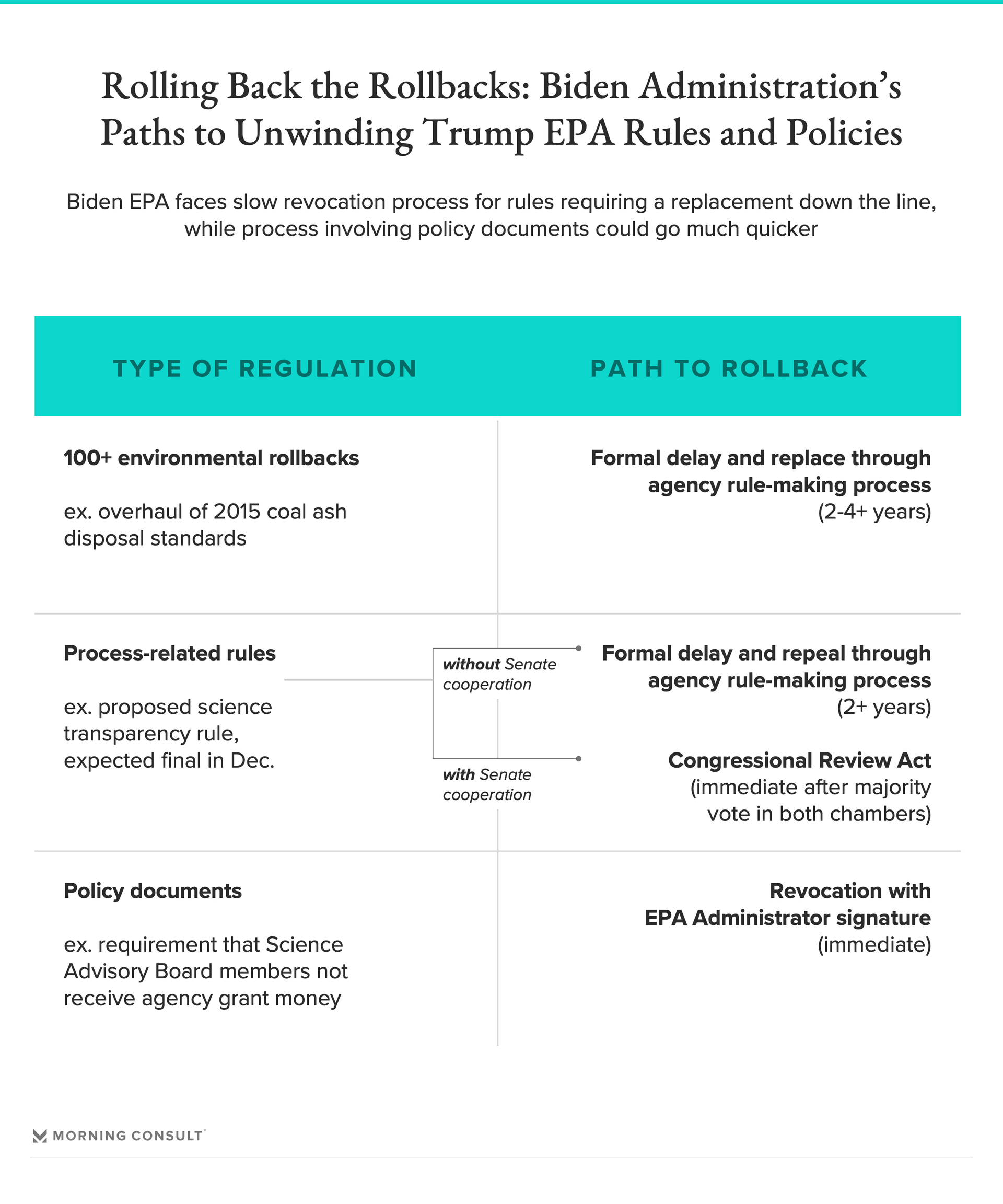

Rolling back the Trump administration’s environmental rollbacks might be easier said than done, former Environmental Protection Agency officials say. As President-elect Joe Biden transitions into office, his administration will be faced with how to strengthen the litany of weakened environmental regulations that will be its predecessors’ legacy, a task that could involve multiple paths depending on the rule in question.

“The Biden EPA is going to have to prioritize,” said Betsy Southerland, who worked at the EPA for 30 years, including most recently as director of science and technology in the Office of Water before stepping down in July 2017. “They can’t just agree to redo every single Trump rule or they’ll spend their entire four years just trying to undo the damage of the past four years.”

Southerland expects the agency to zero in on the rules that have caused the most public health damage, especially those that affect “communities who are disproportionately impacted by pollution.” But even if Biden’s administration is choosy about which of the more than 100 environmental rollbacks to revoke once it takes over in January, it is facing a slog.

Rules that will require replacement -- such as one overhauling 2015 coal ash disposal standards -- will face a process of two years if not more, given that reversing each rollback will require the EPA to take public comment and respond, and then complete a cost-benefit analysis before proposing a more stringent rule to replace the weaker Trump-era version.

But one-off rules constraining the science or policymaking of the agency stand a chance at a quicker process if Congress cooperates to utilize the Congressional Review Act, which allows the legislature to overrule a new regulation through a joint resolution passed with a simple majority.

Meanwhile, policy documents that never went through the formal rulemaking and public comment process are a bit less complex. These documents, which include a mandate that those receiving EPA grant money cannot serve on its Science Advisory Board, can be undone with the stroke of the new EPA administrator’s pen.

The controversial scientific integrity rule, currently at the Office of Management and Budget and expected to be signed in December, is a poster child for the second group. First proposed in April 2018, it would require that regulatory science underlying significant EPA regulatory decisions be publicly available, independently replicable and verifiable. The proposal amassed nearly 1 million comments, many of which noted that the proposal would dramatically limit the research available to the EPA.

And a supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking posted in March would expand the scope of the proposal to block the EPA from distributing “influential scientific information” based on studies not considered transparent under the rule.

Southerland calls the CRA a perfect mechanism to take down the scientific transparency rule because the act’s “poison pill” blocks the agency from issuing a similar rule in the future, unless it is given legislative authority to do so. For comparison, the weakened air and water pollution regulations would be unlikely candidates for the CRA, she said, because the agency will want to replace them with stricter iterations.

“No future administration, I think, would ever want to limit this one agency in the entire U.S. government from using the most up-to-date and most consequential public health information in the world,” she said, referencing the fact that many public health studies — such as those involving the exposure of a population to pollutants — are natural experiments and therefore not replicable.

Another proposed rule that Southerland said would be a likely candidate for complete revocation under the CRA would establish cost-benefit analysis requirements for rules issued under the Clean Air Act, which is also at OMB and expected to be finalized and signed in December or January.

However, if the Democrats do not win control of the Senate in Georgia’s run-off elections in January (and cannot get the requisite number of GOP senators on board), the several rules with CRA potential will have to proceed through the same two-plus-year revocation process as the first bucket of rules, with one caveat: Because the Biden administration likely has no plans to replace these restrictions to policymaking, they won’t have to simultaneously go through the replacement process.

Southerland expects the agency would propose delaying the effective date for these rules and repealing them simultaneously, a process that would take a minimum of two years.

The current EPA did not respond directly to questions about whether it still plans to finalize the science transparency rule before Biden’s inauguration, though spokesperson James Hewitt said in an email that the agency “continues to advance the President’s commitment to meaningful environmental progress while moving forward with our regulatory reform agenda.”

Chris Zarba, former director of the EPA’s Science Advisory Board, is hopeful that “the public has a clearer picture of how science is important and how to listen to it, because of COVID.” Even if it’s not in the environmental realm, he said, science and scientists have taken center stage in 2020.

The United States “kind of ignored science in dealing with COVID and the consequences of that. We had experts that we were making fun of and that we didn’t listen to, and now a quarter million Americans have died,” Zarba said. “It’s the same scale of mortality if you look at science and how it’s been rejected on some of the environmental issues,” he added, referring to the health impacts of projected increases in particulate matter and other pollutants as a result of environmental rollbacks.

Lisa Martine Jenkins previously worked at Morning Consult as a senior reporter covering energy and climate change.