Heading Into 2020, Sickle Cell Community Welcomes Next Generation of Treatment

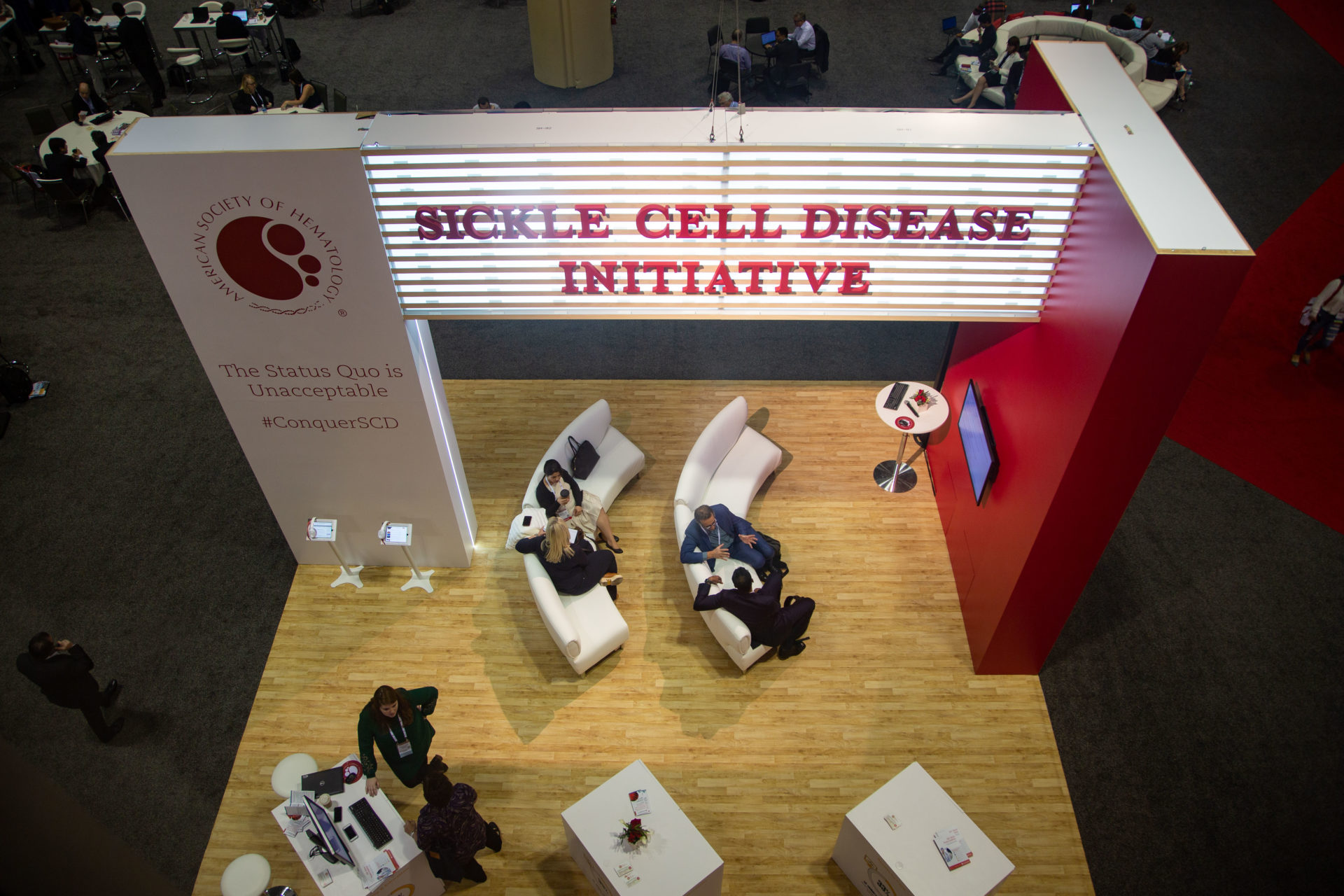

ORLANDO -- When over 29,000 hematologists, blood disease experts and drugmakers gathered for the American Society of Hematology’s annual conference in December 2018, 20 years had passed since a new treatment for sickle cell disease had come to market. In Orlando this past weekend, all eyes were on two new, first-of-their-kind drugs approved in November — within two weeks of each other — with dozens more in the pipeline.

The introduction of a fresh wave of resources for the study of new treatments comes as public health experts and scientists usher in a new era of treatment for the most common inherited red blood cell disorder in the United States, afflicting roughly 100,000 people, predominantly African Americans. For decades, patients’ only treatment options have been medications offering temporary relief from severe bouts of pain.

That changed last month. On Nov. 15, Novartis AG won accelerated approval from the Food and Drug Administration for Adakveo, a monthly infusion that reduced pain crises almost by 45 percent in clinical trials. Ten days later, federal regulators approved Global Blood Therapeutics Inc.’s Oxbryta, a drug to prevent red blood cells from forming the destructive “sickle” shape that gives the disease its name.

Ify Osunkwo, director of the Sickle Cell Disease Enterprise at The Levine Cancer Institute and an official spokesperson for ASH, said while attention to sickle cell has been simmering for the past few years, 2019 marked a turning point. The emergence of two novel drugs and new research on two more caused “a lot of buzz” among hematologists, rounding out what she called “the year of gene therapy for sickle cell disease.”

At the conference, Bluebird Bio Inc. reported for the first time positive results from a small study of its treatment on sickle cell patients — finding one infusion of the gene therapy treatment has the potential to completely halt pain crises. And in mid-November, CRISPR Therapeutics and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc. announced promising results for the first two patients with severe hemoglobinopathies to undergo their gene-editing therapy, for which they are also seeking fast-track approval.

Eleanor Celeste, the associate director of research and development communications at Vertex, said current protocol allows the company to expand its clinical trials to up to 45 patients, and the company will remain in “constant discussions” with regulators about their timeline for approval.

While stakeholders in the sickle cell community are celebrating having reached the brink of what they expect to be a new generation of disease-modifying therapies, the apex is yet to come.

Anytime several drugmakers are targeting the same disease area, a road fraught with competition could be on the horizon. But in these early days, the landscape is far more collaborative than combative.

Ted Love, chief executive officer of Global Blood Therapeutics, challenged the notion that Novartis’ Adakveo poses a threat to his company’s product. The two treatments have different targets, he said, expressing optimism for GBT’s future as a leader “especially in terms of pharmacologic treatment directed at the root cause of the disease.”

“We want to make this a well-managed chronic disease, and we want to do it all over the world,” Love said. Dozens of drugmakers — particularly smaller companies still seeking funding — are exploring this space, and Love said many have reached out to GBT with hopes of working together.

In the same vein, Celeste noted the more options patients have, the better; a Novartis spokesperson said the company is excited by the prospect of reimagining medicine “together with the sickle cell community.”

The nascent field of gene therapy, which hit its stride this year, has unlocked an opportunity for tackling sickle cell that was inconceivable just years ago, experts said. While hydroxyurea, the de-facto standard of treatment since its 1998 approval, can meaningfully reduce the frequency of pain crises, potentially curative treatments offer hope of eliminating crises altogether.

Over the weekend, ASH released its highly awaited full set of new clinical guidelines for sickle-cell treatment — the most comprehensive slate of recommendations to date — with even more nearing completion.

Since the passage of the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 provided financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies to focus on rare diseases, experts have been troubled by a lack of consistency in evaluation of clinical trials. The new guidelines come as drugmakers such as GBT, Novartis and Bluebird establish themselves in this space, offering researchers a uniform, measurable framework for trials to demonstrate the value of their experimental treatments.

All stakeholders agreed that this is only the beginning. Orphan drugs are estimated to comprise one-fifth of global prescription sales by 2024, according to EvaluatePharma, and blood is the leading therapeutic area by sales and market share.

As with any new drugs, uncertainties on cost loom. But experts swiftly rejected the idea that those concerns should dampen the renewed energy around tackling sickle cell, and said attempts to do so may be rooted in prejudice — given sickle cell’s disproportionate impact on black communities.

Therapies for cancers, cystic fibrosis and hemophilia are routinely priced in the hundreds of thousands and even millions, Osunkwo said. The fact that those treatments are widely celebrated as worthwhile endeavors, while the cost of gene therapy for sickle cell is under a microscope before even winning approval, is “stigmatizing” and rooted in “conscious bias,” she said.

Both Novartis and GBT said they are actively talking with payers to facilitate coverage for their drugs, both priced around $100,000 per year, and are taking steps to shoulder some of the burden with their own patient support centers.

“We should have at least another two drugs, if not more, by next year,” Osunkwo said. “The sickle cell community is riled up, ready to participate in clinical trials and do what it takes to get more tools in their treatment toolbox. And they're ready to speak out about how unfair health care and research has been to their cause.”

Yusra Murad previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.