In the Emergency Room, Patients’ Unmet Social Needs and Health Needs Converge

Kneeling gently in his garden this past spring, Lawrence touched the soil beneath his lilies with one hand and held his chest with the other. The fragrance had always offered temporary respite from the searing pain to which he’d grown accustomed -- but this time, he couldn’t breathe.

A team of physicians would later confirm they couldn’t determine whether his aortic valve collapsed that afternoon, or at some other point in the past 10 years he had forgone care. The voices of doctors explaining his options grew distant -- considering the weight of factors out of his control, one medical decision would be a drop in the ocean.

A Christmas Eve stroke in his mid-50s, 10 years earlier, had forced Lawrence to declare bankruptcy. Visiting the doctor would have required a job that brought him home before late evening -- hardly an option given that the nearest jobs were 30 miles from his rural town on the outskirts of St. Paul, Minn. And after paying his premium, shelling out any copay at the pharmacy would drain what little cash remained for groceries.

Lawrence, who requested his last name not be revealed, said he had grown “disgusted” with a health system he deemed unworkable: “The entire country only works if you’re rich and healthy.”

The social and environmental conditions underlying Lawrence’s experience are painfully familiar to the millions of Americans who feel powerless over their health, given the entrenched political and socioeconomic factors shaping the circumstances in which they live and work. As outcomes worsen, public health advocates are pushing policymakers to explore this paradigm -- the social determinants of health -- and investigate the dynamics between individual risk factors and the public policies that precipitate disparities in sickness and health.

Experts studying the social determinants have long focused on the emergency room, where the consequences of such social disparities are on display. A Morning Consult analysis of the relationship between emergency department visits at the state level and 28 indicators of the determinants reveals a strong relationship between ED use and markers of education, employment and mental health in states with the highest and lowest use of emergency care.

The findings underscore warnings from researchers that focusing entirely on the cost of services is misguided; the question of how to extend affordable coverage to everyone is inextricably linked to the social and environmental factors that bar people from accessing care and prevent those who do have insurance from using it.

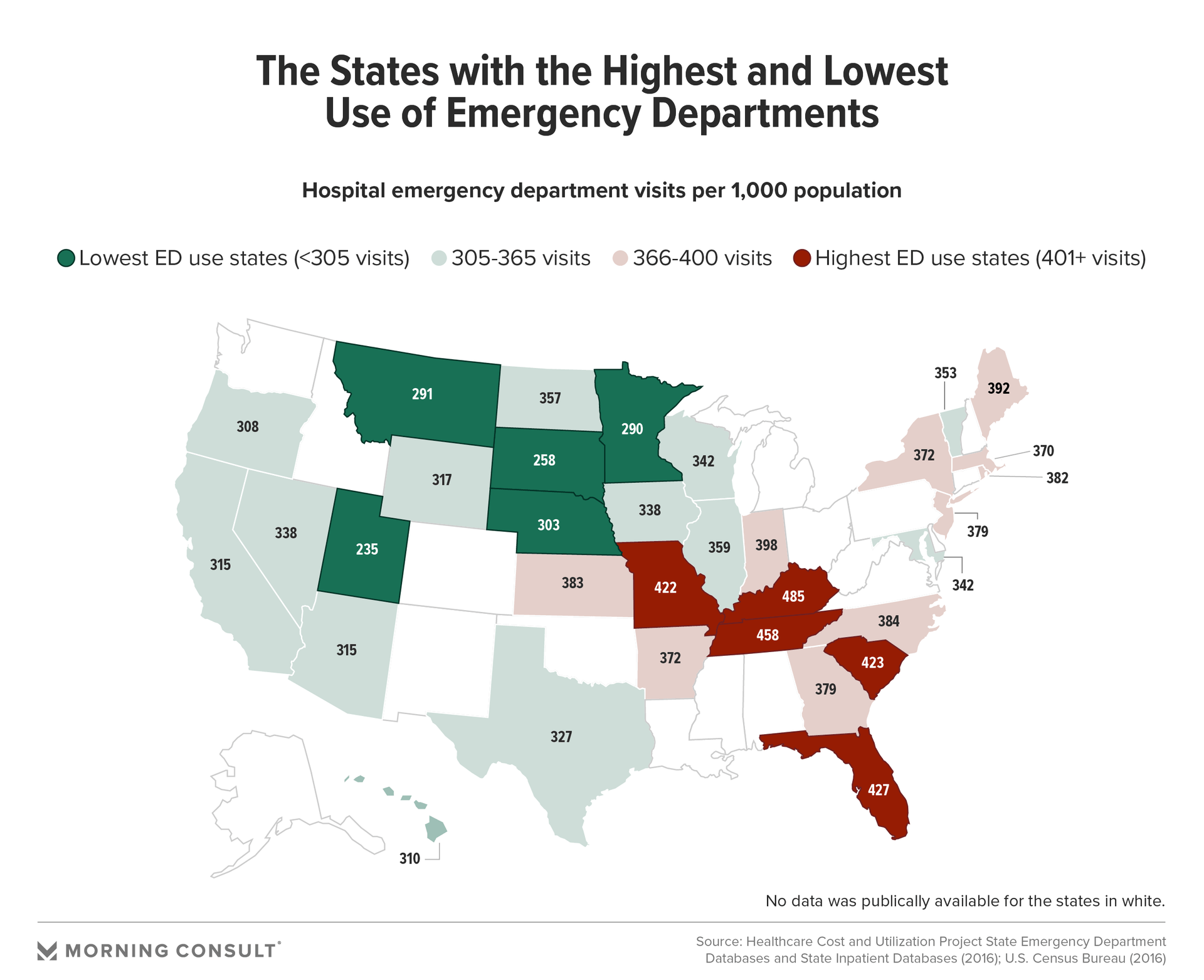

Calculations using data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, the largest collection of longitudinal hospital care data in the United States, show that in 2016, Kentucky, Tennessee, Florida, South Carolina and Missouri saw the highest ratios of total visits to population -- but not because their residents are inherently sicker. The analysis found performance on measures that historically fall outside the realm of health care -- like education, employment and poverty concentration -- had nearly as strong a relationship with ED use as health status.

(The database did not have publicly available figures for 17 states. A detailed explanation of the methodology can be found here.)

Garth Graham, president of the Aetna Foundation and vice president of community health and impact for CVS Health Corp., said the data accentuates the urgent need to look beyond statistics collected in the health system and toward the communities in which those patients live, work and engage.

“Even something we track as clinically basic as ED use is still multipronged in the things that drive it, and just giving you access to a primary care doctor is not the individual end-all solution,” Graham said.

Some of those drivers, like the indicators highlighted in the analysis, are more tangible. But social needs are manifestations of structural conditions and policy decisions that shape the social determinants of health, meaning that within the social determinants paradigm, there are midstream and upstream interventions. While upstream solutions address structural issues of resource allocation and economic opportunity, midstream interventions are critical in mitigating the consequences of those inequities.

Education is one such example. A common denominator among states with high use of emergency care is that their performance on education measures -- including the population with at least some college education and portion of young people studying or working -- ranked near the bottom of the 33 states included in the analysis.

Improving poor mental health status -- one of the markers with the highest positive relationship with ED use -- is another opportunity for a midstream intervention. All five states with the highest ED use ranked in the bottom-most percentile on mental health.

Susan Beane, executive medical director of provider-sponsored health plan Healthfirst, noted the integration of behavioral and physical health services can prevent the acceleration of worsening health conditions.

As Lawrence’s doctor told him: It’s nearly impossible to measure the toll that nearly losing a home takes on one’s mind and body.

According to Ben Isgur, who leads PwC's Health Research Institute, going upstream gets to the question at the core of the paradigm: “Can we stop people from needing these very expensive services to begin with?”

Addressing social needs has risen to a top agenda item for powerhouses in the health industry, but it’s been a long time in the making. Housing, for example, has been a focus of payers for decades; Aetna Inc.’s investments in housing, such as building and renovating thousands of affordable rental units, date back to the 1990s.

Experts say the impetus for recent acceleration, from a policy perspective, is twofold. At the local level, those engaged with Medicaid beneficiaries have witnessed the profound effect of socioeconomic disparity emerge repeatedly in the data. On a broader scale, the systemwide shift from a fee-for-service model to value-based care reveals stark inconsistencies in outcomes for recipients of identical medical care.

Health systems are similarly looking more intentionally at social needs as the transition from a volume- to value-based system adds a layer of financial accountability. Instead of receiving reimbursements based on the number of patients or procedures, many systems are paid depending on how patients fare after they leave the hospital.

“When you look at what impacts an individual's health the most, those things happen outside of our clinical care walls,” said Alisahah Cole, chief community impact officer at Atrium Health, one of the nation’s largest health systems.

In 2016, Atrium, finding elevated rates of illness and unneeded emergency care in areas with high social need, saw an opportunity to arm doctors with the necessary context for their patients by merging assessment tools and population health data with its electronic health records system, Cerner Corp.

According to Cole, “one of the things we consistently heard in the beginning was, ‘OK, I can ask my patients if they're food insecure. But what do I do when they say yes?’ ”

To ensure clinicians can meaningfully respond to patients’ social needs, Atrium partnered with a cloud-based community resource hub, opening channels of communication between providers, care managers and social workers to connect patients with local organizations focused on key drivers to improve health.

Efforts to maximize collaboration with local groups speak to a guiding principle of the social determinants: Sickness in a community is a reflection of intersecting challenges barring local infrastructure from meeting residents’ needs.

Denard Cummings, director of the Bureau of Social Determinants of Health at the New York State Department of Health, said locally run organizations’ “trust, knowledge, cultural competency and ability to navigate the community” make them a key component of the state’s health initiatives.

Under New York’s framework for value-based care, medium- and high-level value-based payment arrangements must include coordination with at least one nonprofit, non-Medicaid billing, community-based organization.

The estimated cost of waste attributable to failure of care coordination is between $27.2 billion and $78.2 billion, according to a study published in JAMA. William Shrank, chief medical officer at Humana Inc., said waste in every aspect of the health care system could be reduced by addressing social needs, but especially in this realm.

“What if you're discharged from the hospital and don’t have access to healthy food?” Shrank said. “What if you're getting discharged from the hospital and don't have a home?”

There are other similarities among the five states with the highest ED use. Save for one, none have expanded Medicaid; the opposite is true for the states with the lowest ED use. But as the analysis reveals, because health is interlaced with myriad policy areas affecting individuals’ daily lives, there is no shortage of meaningful -- and less politically fraught -- opportunities.

Beane of Healthfirst said the rising tide of integrating health care with social services provides a framework for conceptualizing health care not just as medical treatment, but whole-person care.

Shrank said the United States is “wildly over-indexed” on health care spending and under-indexed on social services. In his view, that means health companies are uniquely positioned to seize an opportunity in a political landscape that is hostile to increased funding for social programs by using millions of dollars earmarked for health care to address social needs and benefit financially from making investments that prioritize prevention.

Isgur said the U.S. health system lacks incentives to take care of the “whole person." Instead of connecting individuals with the social support they need to prevent readmission, the system has largely divorced itself from what happens the moment after discharge.

In Lawrence’s case, an aortic valve replacement saved his life, but while awaiting medical bills with the threat of eviction looming, he regularly experiences panic attacks and despair.

“Nobody calls. Nobody even picks up, unless I’m calling about the bill,” Lawrence said. “Sometimes I wish I had just died then.”

While interventions led by private companies are critical in mediating social needs stemming from underlying social and economic disparity in the interim, the crux of the issue requires challenging those structural conditions that precipitate poor health. And that, experts say, demands bulletproof resolve and systemic resource allocation championed at the national level.

“We often are talking about leadership, and it does take bold, innovative leadership to address social determinants,” Atrium’s Cole said. “But we're a little beyond that. We've been asking people to lead in a broken system. What we really need to be doing is re-engineering a new system that is equitable and fair.”

Morning Consult data scientist Matt Kosko contributed to the data analysis.

Yusra Murad previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.