As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

Key Takeaways

Public opinion in South Korea of Japan and the United States has declined as Seoul has pushed for closer ties, but security realities leave the unpopular Yoon with no realistic alternative policy.

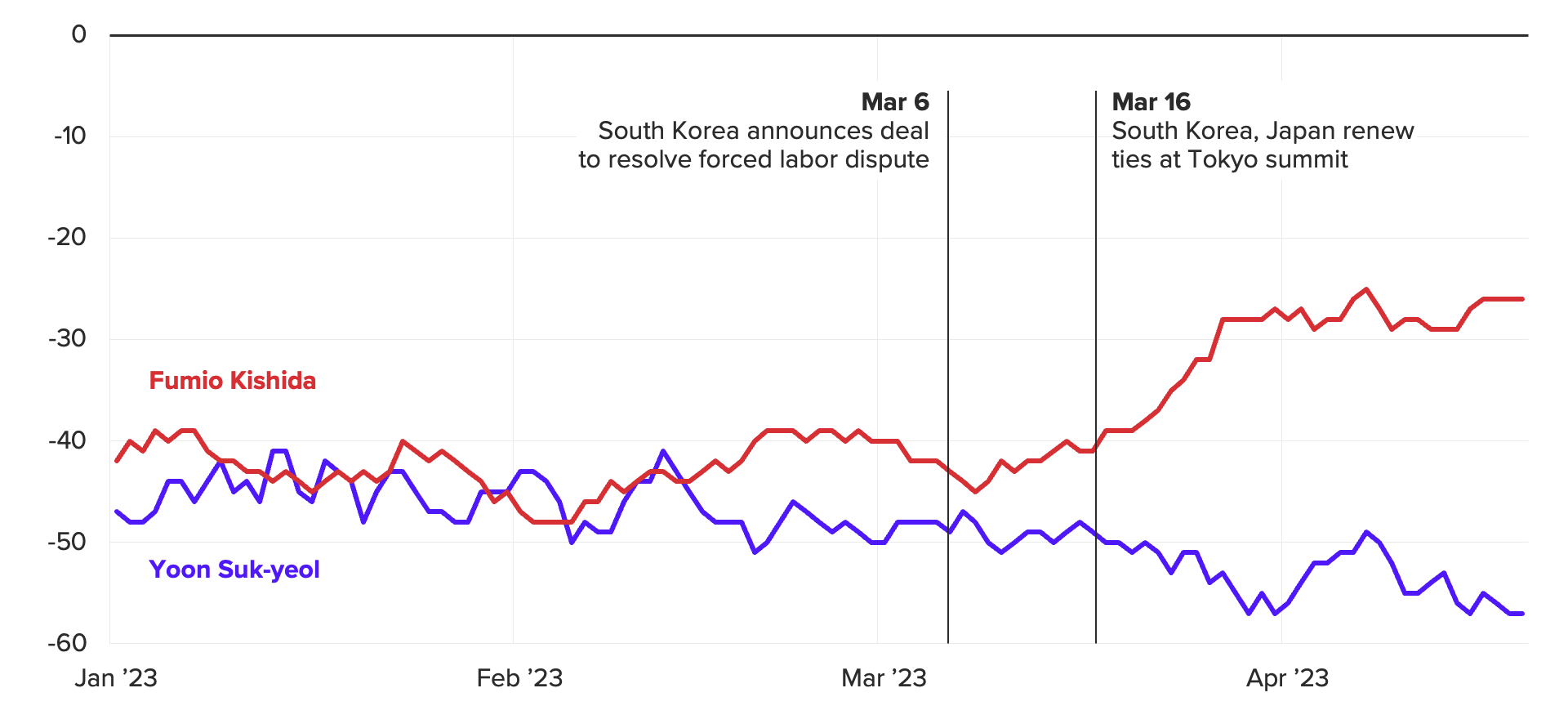

While Yoon’s standing has continued to deteriorate as he attempts to redirect Seoul’s foreign policy, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has reaped political benefit, reversing a nearly yearlong slide in his approval rating.

Get the latest news and analysis on how business, politics and economics intersect around the world delivered to your inbox every morning.

South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol’s summit with President Joe Biden on Wednesday is a crucial opportunity for Seoul to bolster ties with both Washington and Tokyo, but Morning Consult surveys suggest public opinion in South Korea presents major obstacles.

Yoon, who consistently ranks as one of the most unpopular leaders in Morning Consult tracking, is facing scathing criticism at home for his attempts at reconciliation with Japan despite serious historical grievances. Even so, Yoon has so far gritted his teeth and pushed forward, as the threats presented by North Korea and China are too great for South Korea to face alone.

“Yoon has made a strategic and courageous policy shift to avoid being isolated in East Asia,” said Ken Moriyasu, a diplomatic correspondent at Nikkei Asia.

The good news is that Biden and Yoon are well-positioned to reach agreements that could do much to reinforce their alliance and collective security in East Asia. The bad news for Yoon is that Morning Consult surveys show South Koreans are so out of step with him on his foreign policy pivot that it may be hurting public opinion of the country’s most important allies.

South Koreans Sour on Japan and the United States

South Koreans cool on Japan and United States as Yoon seeks closer ties

Between December — before Yoon’s charm offensive to Tokyo and Washington — and April, views in South Korea of Japan and the United States declined significantly. Among South Korean adults, Japan’s net favorability — the share of respondents with favorable views minus the share with unfavorable views — fell 12 percentage points to minus 43, while net favorability of the United States plummeted 16 points to plus 29.

The feelings are not mutual. South Korea’s net favorability among Japanese adults increased 13 points over that period (though it remains underwater at minus 26), while views of the United States remained firmly positive. Americans’ views toward both allies also held steady, though feelings toward Japan are considerably more positive.

The divergent trends can be traced in part to a historic deal reached in March between Seoul and Tokyo to compensate South Korean victims of forced labor by Japan during World War II. Under the plan, South Korea would raise local funds to compensate the victims and Japanese companies wouldn’t be required to contribute. Biden called the deal “a groundbreaking new chapter of cooperation” between the two countries, but the deal has faced substantial criticism in South Korea over concerns that Japan escaped responsibility for its abuses.

Despite the decline in approval of Japan and the United States, South Koreans’ views of the three countries’ shared rivals could hardly be worse. The net favorability of China, Russia and North Korea among South Korean adults stands at minus 84, minus 82 and minus 84, respectively. And those rock-bottom views — particularly of China — may open a narrow path for Yoon in South Korea’s outreach to Japan and the United States.

Until recently, “South Korea was always hesitant to align too closely with America and Japan in countering China, because good relations with China were seen as crucial for security,” Moriyasu said.

That’s because historically many in South Korea saw China as a partner that might rein in North Korea, and as recently as 2014, a Pew survey showed that a majority of South Koreans had favorable views of China. But over the past decade, Beijing has demonstrated it is either unable or uninterested in halting North Korean nuclear and missile tests. China also damaged its image in South Korea with harsh rhetorical and economic retaliation over South Korea’s deployment of American-made missile defense systems in 2016.

Yoon and Biden have an opportunity for a major breakthrough

With the strategic impasse over China largely removed, interesting possibilities arise. For his part, Yoon has been signaling he is coming to town ready to make a major deal regarding another major conflict: Russia’s war in Ukraine, according to Sheryn Lee, a senior lecturer at the Swedish Defense University who focuses on Indo-Pacific defense policy.

“The ammunition shortages in Europe are extremely severe and South Korea is one of the only countries that can possibly step in with more supply,” said Lee, adding that Yoon set a low bar when he said last week that South Korea might start sending weapons to Ukraine if Russia commits “any large-scale attack on civilians, massacre or serious violation of the laws of war.”

The Biden administration also wants Seoul to encourage South Korean chipmakers not to export their products to China should Beijing ban U.S. chipmaker Micron Technology Inc.

Yoon’s domestic position is already suffering from perceptions of overly deferential foreign policy, and he will need something from Biden in return, Lee said. Yoon might ask Biden for more intelligence sharing and for South Korea’s participation in American-led multilateral projects like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and AUKUS.

Of course, most of the concessions in that area would require Tokyo’s assent. Historically, Japan has been hesitant to bring South Korea into high-level multilateral arrangements such as the Quad for its own reasons, Moriyasu said.

“For the longest time, Japan tried to find ways to exclude South Korea from the G-7, for example, in part because Japan is the sole Asian representative there,” he said.

However, the winds may now be blowing more favorably for diplomatic breakthroughs between the two countries. Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has seen a much-needed rally in his approval rating as Japan has renewed ties with South Korea, even as Yoon’s backing continues to slide.

Yoon’s Approval Suffers During Rapprochement With Japan, While Kishida’s Improves

Since the two leaders’ historic summit in Tokyo on March 16, Kishida’s approval rating has increased 8 points to 30%, while Yoon’s has declined 3 points to 19%.

“Yoon had to make a difficult choice; getting along with Japan and making concessions to Japan is never a popular thing in South Korean politics,” said Joshua Stanton, a lawyer who has assisted Congress with the drafting of North Korea-related legislation and advised the Justice Department in sanctions enforcement cases.

Kishida may be hesitant to fully embrace Yoon because South Korea’s notoriously fickle and hardball domestic politics have burned Tokyo before, as previous administrations have repudiated their predecessors’ agreements with Japan upon coming to power.

But just as changing circumstances have forced Yoon’s hand, the same systematic shifts are pushing Tokyo closer to Seoul, according to Moriyasu.

“Today, Japan realizes it cannot reduce tensions with China, Russia or North Korea,” he said, “but it could mend its ties with South Korea to better protect itself.”

Matthew Kendrick previously worked at Morning Consult as a data reporter covering geopolitics and foreign affairs.

Related content

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade

Some GOP Lawmakers Want to Overhaul the Tax System. Voters Are Mostly Against Their Plan