In Robust Job Market, Gig Workers’ Satisfaction on Par With Wider Workforce

Key Takeaways

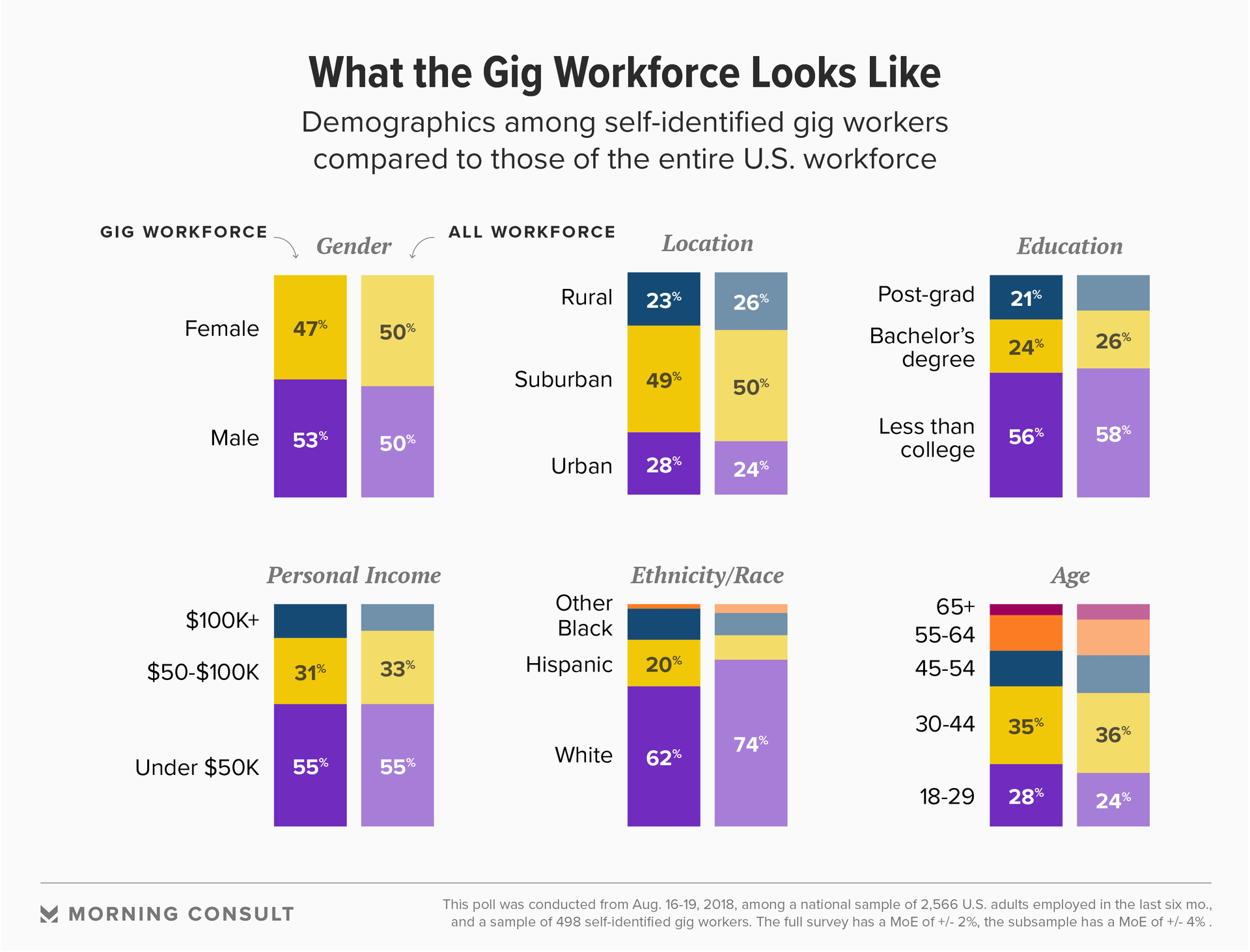

Hispanic workers account for 20% of the gig workforce, double of that in the overall workforce (10%); African-Americans make up 12% of gig workers, 8% of all.

Gig workers were split on whether they’d stay in the gig economy: 51% said they would, but 49% would prefer a full-time position.

51% of all adults employed in the last six months said they’d pick more flexibility and shorter hours even if it meant less pay; 34% preferred more pay despite longer hours.

As the explosion in the use of the internet and mobile devices has fueled the growth of freelance, contracting and piece work, worries about the so-called gig economy have risen in tandem. Lacking company-provided benefits such as health insurance and employee-sponsored retirement savings accounts, many gig economy workers generally face more constant instability in their jobs than their counterparts who work full time at companies.

But a new Morning Consult survey, conducted online Aug. 16-19, shows that adults who identify as being a gig economy worker report being just as satisfied with their jobs, financial situations and family life as the average adult who has been employed in the past six months. Gig workers also report similar satisfaction rates on pay, benefits, required hours, work-life balance and other working conditions.

Out of a national sample of 2,566 adults employed in the last six months, 19.4 percent, or 498, self-identified as gig economy workers, which the survey defined as those who accrue a considerable amount of their income from a series of freelance and contract jobs and included both full-time and part-time gig workers. The full survey has a margin of error of 2 percentage points; the subsample of gig economy workers has a margin of error of 3.9 percentage points.

In the survey, 80 percent of gig workers said they are satisfied with their current job, and 59 percent are satisfied with their financial situation. That is compared to 78 percent of all workers who said they are satisfied with their current jobs and 62 percent satisfied with their current financial situation.

Gig workers surveyed also show similar satisfaction with their pay (69 percent), benefits (64 percent) and required hours (75 percent) to the entire workforce, where 68 percent are satisfied with pay, 67 percent with benefits and 78 percent with the required hours.

Yet Louis Hyman, director of Cornell University’s Institute for Workplace Studies, said it’s important to consider the context for gig work and job satisfaction, especially considering that contractors on certain gig platforms were sold a specific image.

“There is this fantasy that you can work in this space and make good money even though you don’t have a job or skill set more complicated than driving a car,” he said. “That’s an issue. It’s not delivering to working-class Americans any better than the rest of the economy.”

The survey data is set against the backdrop of a robust wider U.S. economy: The latest Labor Department employment data, released Sept. 7, showed 201,000 jobs were added in August, and hourly wages rose 2.9 percent from a year earlier. The unemployment rate stayed at 3.9 percent.

How much the gig economy has grown in recent years is a matter of debate, with researchers noting that varying terminology and research methods in surveys can yield different results.

“Some people just look at people who work on online platforms as the gig economy; some look at the broader categories of independent work as a proxy of the gig economy,” Alastair Fitzpayne, executive director of the Aspen Institute’s Future of Work Initiative, said in a phone interview.

In June, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its first update to its report on alternative work arrangements in more than a decade, based on a survey conducted in May 2017, which includes contingent workers, independent contractors, temporary help agency workers, on-call workers, and workers provided by contract firms, and it only focuses on full-time work.

Considering those definitions, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports the contingent workforce makes up 1.3 percent to 3.8 percent of total employment and 10.1 percent participated in alternative arrangements, with a possible small overlap between the two groups.

Shelly Steward, research manager for the Future of Work Initiative, said the number of people engaging in this work has increased based on tax data, and most of those increases have been in supplemental work, like side jobs or gigs.

“Some form of contingent and supplemental work has existed for as long as work has existed, but the advent of smartphones and apps and platform technology has changed the way that you enter some of those arrangements,” Steward said. “With that change it becomes more acceptable.”

While the Morning Consult survey shows most gig workers (67 percent) reported turning to contract work now for supplementary income, as opposed to their main income (33 percent), Hyman predicts the motivations of those workers will be different during the next recession.

“When the next recession comes, corporations will shed their workers; those workers will look around and try to find gig jobs,” he said in an interview after the August jobs numbers were released. “Those core corporate jobs are going to dry up pretty rapidly.”

Among gig workers in the survey, most of them are male (53 percent), white (62 percent), between the ages of 18-44 (63 percent), make under $50,000 each year (55 percent), don’t have a college degree (56 percent) and a plurality are based in suburbs (49 percent).

Hispanic workers make up twice as much of the gig workforce (20 percent) as they do the overall workforce (10 percent). The gig workforce also has more African-American workers (12 percent), compared to the overall workforce (8.8 9 percent).

Gig workers are often pitched on the economy with the idea of creating a flexible schedule, being their own bosses and having the ability to pick and choose their own projects or assignments — and by some measures it appears to be working. Forty-seven percent of working millennials and 36 percent of the current U.S. workforce are freelancers already, according to Upwork and Freelancers Union’s “Freelancing in America” 2017 report released in October. The report also forecasts a majority of the U.S. workforce will be freelancing by 2027.

In the Morning Consult survey, when given a choice between pay and flexible hours, 51 percent of all workers said they’d pick more flexibility and shorter hours even if it meant less pay, while 34 percent preferred to make more money even if it resulted in less flexibility and longer hours. Fifty-five percent of gig workers make less than $50,000 annually before taxes — the same share as all workers.

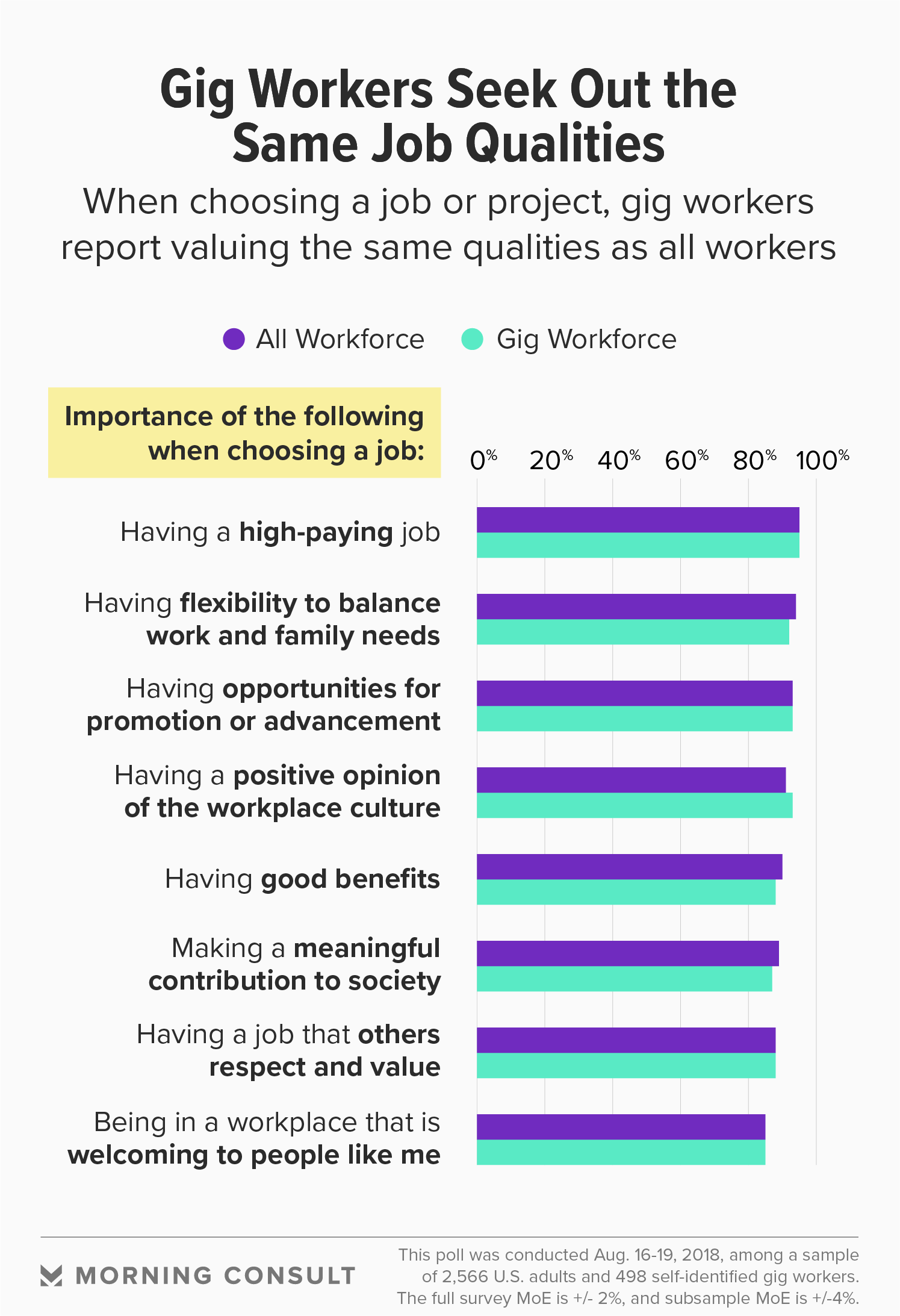

Gig workers also value the same characteristics as the overall workforce when considering a potential job, with 95 percent of both groups saying having flexibility to balance work and family needs is important.

However, gig economy workers were divided on whether they’d keep doing what they were doing: If given the opportunity, 51 percent said they’d want to stay as a gig worker and 49 percent said they’d prefer to work a full-time position.

Hyman said that while the idea of more flexibility is alluring to workers, they still need to scrape together enough work to cover their living costs, which limits their flexibility in practice.

“You get some choice over where you want to work, but you still have to work,” he said.

At Postmates Inc., a San Francisco-based startup that provides on-demand courier services, Vikrum Aiyer, the company’s vice president of public policy and strategic communications, said the company has “recognized that a fair amount of our Postmates are also not necessarily looking to be Postmates for life.”

Aiyer, who also served as a White House senior adviser on manufacturing and innovation policy in the Obama administration, said internal conversations about how to provide its contractors with worker protections as the gig economy grows are already taking place. Postmates’ goal, he said, is to work with organizations such as labor unions to strike a balance between the benefits of flexible work with the worker protections and benefits of a corporate job.

Independent contractors, a classification that applies to most gig workers, don’t have the same legal worker rights as a company employee, Aiyer said. For example, most federal workplace discrimination laws apply only to employees.

“Since the New Deal, the way that labor laws have been structured in this country not only did not envision the iPhone and the app economy that sprung from that, but it also didn’t envision where we see millennial workforce trends,” Aiyer said.

Sam Sabin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering tech.