Energy

For Urban Homeowners and Renters, the Quality of Affordable Housing Is Debatable. But Both Groups Agree on the Need for More

What Urban Voters Want From the Infrastructure Law

A new special report from Morning Consult explores the priorities of urban voters when it comes to climate change and infrastructure, as funds from the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure law are doled out across the country. The data is drawn from a survey of 1,062 urban U.S. voters. Explore the full series.

Key Takeaways

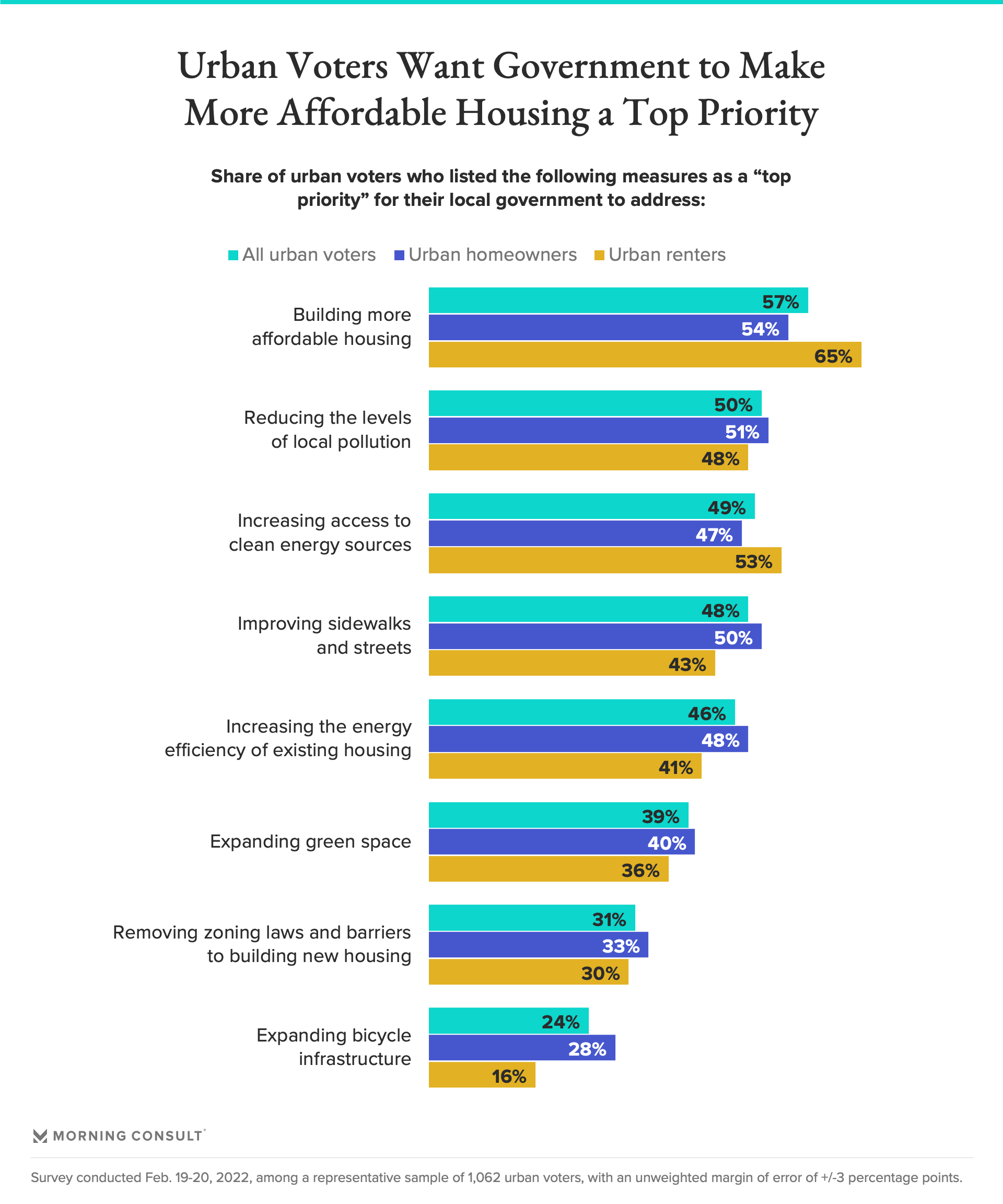

Nearly 3 in 5 urban voters said increasing affordable housing stock should be the biggest priority for their local government, while about half said the same for reducing the levels of local pollution.

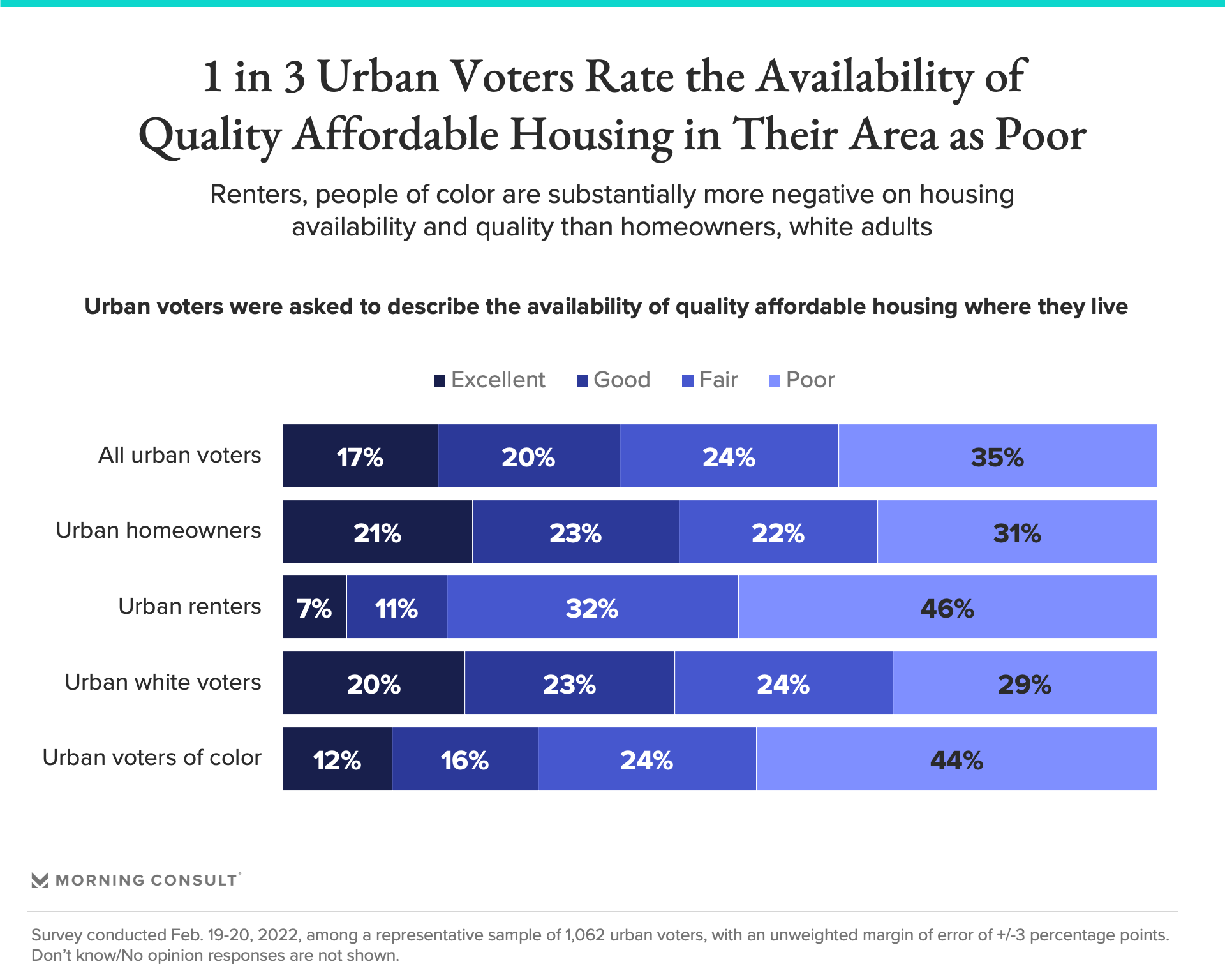

78% of urban renters and 68% of urban voters of color described the availability of quality affordable housing where they live as “fair” or “poor,” compared with 53% of urban homeowners and an equal share of urban white voters.

Roughly 2 in 3 urban homeowners said they’re confident their community will take steps to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change in the next decade; just over half of urban renters said the same.

Months of haggling over what resulted in the $1.2 trillion infrastructure law left myriad policy planks on the proverbial cutting-room floor, with a $300 billion-plus investment in affordable housing sticking out as one especially notable casualty.

President Joe Biden later pacified housing advocacy groups by calling for $150 billion in construction and financial assistance in his Build Back Better plan. But that now-dead legislation — and the apparent lack of interest in the issue from Democrats’ most powerful senator — leaves plenty of unanswered questions about how the president’s goals to boost the country’s affordable housing stock will be met.

Those goals are of particular interest to voters living in urban areas, 57 percent of whom said in a Morning Consult survey that building more affordable housing should be a “top priority” for their local government to address. Another 28 percent said it should be “an important but lower priority.”

While local governments’ hands are tied when it comes to Washington’s “will they or won’t they” dalliance with federal housing investments, the will of urban voters is clear: Majorities of renters, homeowners and people of color view an increase in affordable housing as an imminent need for their communities.

Nikitra Bailey, senior vice president of public policy at the National Fair Housing Alliance, called housing’s omission in the bipartisan infrastructure law “a missed opportunity.”

“Ensuring a stable housing market ensures a stronger economy,” she said. “And studies show that if you address discrimination, including in housing, we have a chance to grow the economy by $1 trillion per year over the next five years. That type of activity would generate thousands of jobs and billions of dollars in local revenue.”

Pandemic worsened housing wealth gap, and urban voters think affordable stock isn’t up to snuff

Seemingly all trends in housing over the past decade — and especially during the pandemic — have benefited the wealthy. Investors have flooded major metropolitan markets, driving up prices and making homeownership even more insurmountable for lower-income Americans.

A National Association of Realtors report this month found that roughly 71 percent of the country’s increased housing wealth went to high-income households from 2010 to 2020, a period in which the total value of owner-occupied homes climbed from about $15.9 trillion to $24.1 trillion. Low-income housing wealth slipped to 19.8 percent of the overall share in 2020, down from 28.2 percent 10 years earlier.

The National Fair Housing Alliance has called on lawmakers to invest in enforcement of fair housing statutes and fund the Neighborhood Homes Investment Act, which would aid in the rehabilitation of homes in lower-income areas and then make them available to owner-occupants.

The same communities that “were hardest hit by the subprime lending crisis” were especially impacted by the pandemic-spurred skyrocketing of housing prices and costs, Bailey said, adding that funding via the Neighborhood Homes Investment Act would help address widening inequality via home renovation.

More urban voters than not see lackluster affordable housing stock where they live: 59 percent described the availability of quality affordable housing in their communities as “fair” or “poor,” compared with 37 percent who said it was “excellent” or “good.”

Renters were substantially more likely than homeowners to characterize affordable housing conditions in their communities as lacking, while a similar split played out between urban voters of color and urban white voters.

"There is an undeniable shortage of affordable housing in America," a Department of Housing and Urban Development spokesperson said. "In many urban communities, there is an especially tight market with high housing costs and low available inventory. As rental costs continue to rise, families are forced to make difficult choices when it comes to essential expenses such as childcare and housing. Rising costs are also making it more difficult for people to enter into homeownership."

The spokesperson noted that the Federal Housing Administration and the Treasury Department relaunched the Federal Financing Bank-Risk Share Initiative, which HUD projects will result in the creation or preservation of approximately 20,000 affordable rental homes, and Congress recently approved $8.5 billion for the agency to distribute for public housing maintenance and operations, an increase of $645 million from last year.

Though federal momentum on affordable housing appears stalled, Carlos Martín, director of the Remodeling Futures Program at Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, said it’s important to note that much of the action needs to happen on the local level anyway.

“It’s the combination of money and access to land, or being able to redevelop existing properties,” said Martín, also a David M. Rubenstein Fellow at Brookings Metro. “A big part of the need is also local zoning and availability of land, to be able to build in some really dense urban environments that are already sort of maxed out in terms of their development.”

Housing policy and climate change are intertwined, and urban voters feel OK about local government action on the latter

When affordable housing was coded as social infrastructure rather than physical — and subsequently shuffled into Biden’s Build Back Better plan — all was not lost for housing advocates. Martín pointed to the billions in funding toward the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program, as well as allocations for hazard and flood mitigation.

In a January paper published in the journal Housing Policy Debate, Martín wrote that housing is “now squarely established within climate policy as part of the strategic toolkit for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and as a channel for addressing the exacerbated social and economic injustice that fossil fuel consumption has wrought.”

These realizations have been clear to Martín and other experts in the field for quite some time, but making the public understand the connection between climate and housing is an ongoing process. “Imagine the consequences of living in an area where a third of the year is going to be above 100 degrees,” Martín said. “So the way you adapt to that is either not live there anymore or have the AC running all the time,” an outcome that would boost emissions and worsen climate change.

In the Morning Consult survey, however, 63 percent of urban voters said they were confident their community would take steps to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change in the next decade.

“That’s very confident — I would say overly confident. Because we haven’t seen most communities actually take any action,” Martín said of those survey results.

About 3 in 5 Urban Voters Are Confident That Their Community Will Address Climate Change

Bailey noted that decades of redlining policies created an environment that has left Black and Latino communities shouldering the brunt of climate change in urban settings, with the federal government’s “history and legacy” of discriminatory housing policies relegating those populations to the “heat deserts of our society.”

To address climate change in urban communities of color, increase affordable housing and narrow the homeownership wealth gap, Bailey sees the discarded housing provisions from the original infrastructure proposal as a chance to make progress on those fronts. She said she hopes the Senate will resurrect them and “pass them without delay.”

“Where you live matters,” Bailey said, adding that those provisions “present an opportunity to provide inclusive growth for everyone.”

Correction: The story has been updated with comment from the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Due to an editorial oversight, HUD's response was added late in the publishing process.

Matt Bracken previously worked at Morning Consult as a senior editor of energy, finance, health and tech.