Brazil’s Place in the World May Be at Stake in Its Coming Election

Key Takeaways

Brazilians are preparing for a turbulent election campaign and aftermath, with President Jair Bolsonaro actively undermining confidence in the integrity of the country’s electoral system as political violence and intimidation proliferate.

Foreign policy is unlikely to play a decisive role in the campaign, but the choice ultimately made by voters will profoundly affect Brazil’s international standing, with Bolsonaro having repudiated Brazil’s longstanding history of multilateral engagement.

Former President Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who is currently ahead in most polls, earned plaudits for his broad engagement and strong relationships with foreign leaders during his first two terms in office, and would be expected to renew such efforts if he wins again — but geopolitical conditions have shifted in the decade since his departure.

Brazilians face one of the most consequential decisions in their country’s history in the Oct. 2 presidential election.

Although domestic issues have pushed foreign policy concerns out of the spotlight, experts say the result of the contest will decide whether Brazil returns to its traditionally pragmatic stance in global affairs or remains internally focused and largely absent from the world stage. And given Brazil’s status as a major emerging market and central role in determining whether humanity can avoid the worst impacts of climate change, its diplomatic direction has deep economic and humanitarian ramifications.

President Jair Bolsonaro — often called the “Trump of the Tropics” for his right-wing populism and iconoclastic style — has sought few strong international partnerships for Brazil since he took power in January 2019, instead tending to treat foreign policy as an extension of his domestic political battles, said Carlos Milani, an associate professor at Rio de Janeiro State University’s Institute of Social and Political Studies and senior fellow at the Brazilian Center for International Relations.

“Bolsonaro’s plans for his foreign policy next term are nonexistent, in the sense that he may take actions in response to lobbying from certain interest groups, but they do not amount to a cohesive policy narrative,” Milani said. “He has rooted many of his public policies, including foreign policy, in an idea of deconstruction, of destruction of the past for the sake of rebuilding an ideal Brazilian society; it’s not rooted in reality or history. That’s why some days Bolsonaro may be a friend of Washington and some days a friend of Moscow.”

But lacking the strategic geography, natural resources or military capacity of other middle powers that play both sides of major power conflicts, such as Turkey or India, the net result of this strategic incoherence has been increasing Brazilian isolation, Milani said.

“Brazil has become a kind of liability in the region. In previous years, Brazil was called by its neighbors to play a mediation role; in Bolivia, in Ecuador, in Venezuela, Brazil was called upon to bring people from different sides together to dialogue,” he said. “Nowadays, with a president who screams at everybody and despises the role of culture and civilized dialogue, who on Earth would call on Brazil to mediate?”

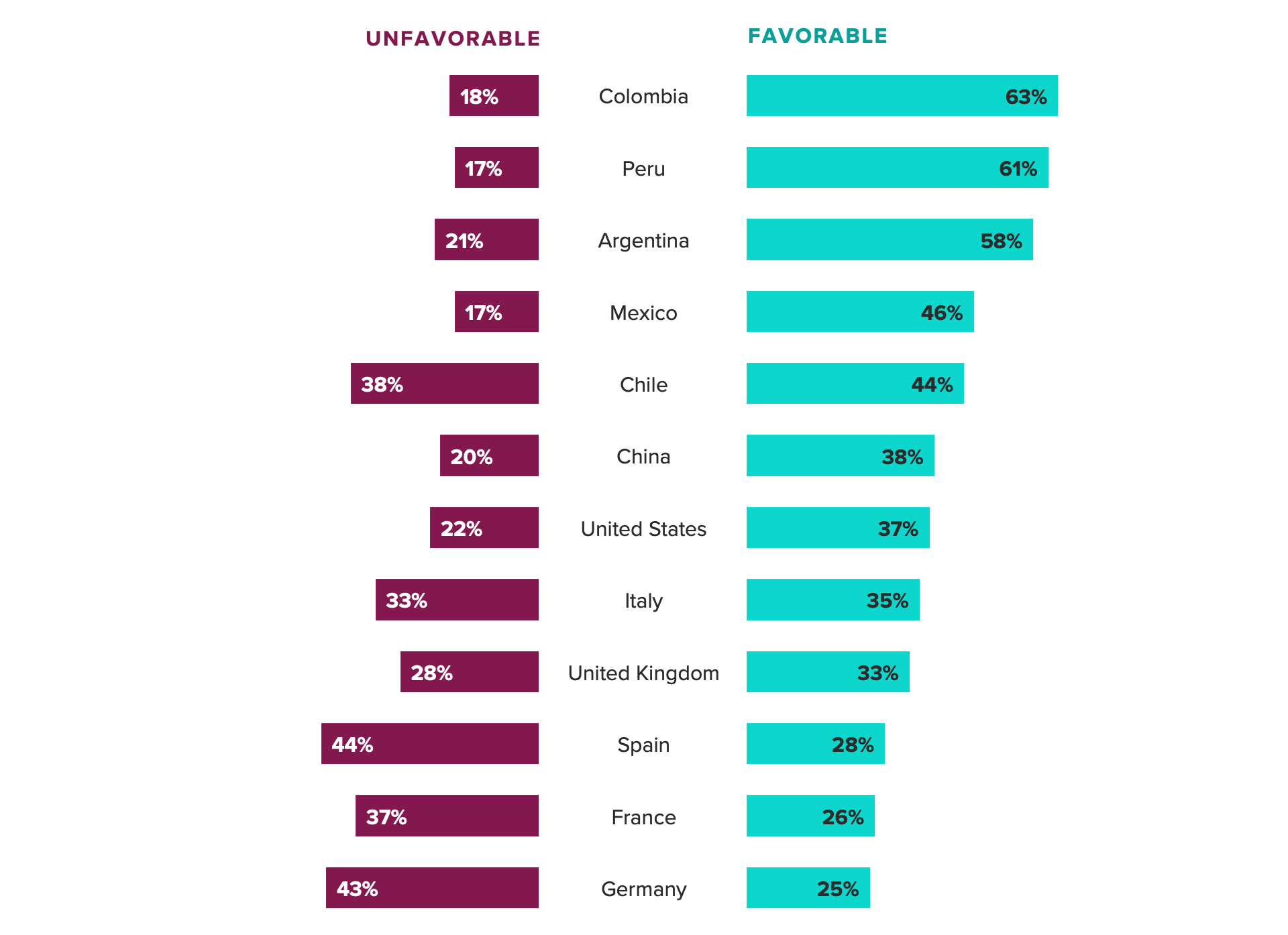

Brazil Is Viewed Most Favorably in Its Own Backyard

Morning Consult surveys conducted June 1-30 around the world show that Brazil is still mostly viewed favorably among its closest neighbors. But its reputation has also suffered dramatic falls when compared to a 2014 Pew study that found Brazil’s global image was overwhelmingly positive under da Silva’s protegé, then-President Dilma Roussef — even in Chile, the United States and Western Europe, where positive views have since plummeted. In 2009, when da Silva was last president, a survey from Latinobarometro found Latin Americans thought of Brazil as even more influential in South America than the United States.

Those declines illustrate how the global soft power of Brazil— which usually punches above its weight with a vibrant culture attracting millions of tourists and commands high levels of respect in the international community, earning it leading roles on peacekeeping, climate and health issues — may erode further. But surveys about foreigners’ opinions won’t concern Bolsonaro.

Brazilian polls consistently put da Silva ahead of Bolsonaro by double-digit margins, and the opposition camp is reportedly already hoping to win an absolute majority in the first round of voting to eliminate the need for a runoff election.

Bolsonaro has reacted by attacking the electoral system, which is regarded as a model of integrity and often imitated in other countries, without presenting any evidence of his claims about its vulnerability to fraud. His polemics have even been echoed by some prominent figures in the military, leading some to fear Bolsonaro may be preparing for a coup d'état, even as the armed forces say they will respect the certified result of the election.

But it’s also too early to discount Bolsonaro’s chances at a legitimate electoral victory, with Brazil suffering the same issues of unreliable polling as many other countries in recent years.

“We have mandatory voting in Brazil, which in theory helps with polling accuracy because it's easier to sample likely voters,” said Natália Aguiar, a political scientist at the Federal University of Minas Gerais in the country’s southeast. “But we have seen abstention growing in every election cycle and that people are increasingly deciding who to vote for in the last week of an election, which makes polling less accurate.”

The president is not without a supporter base, either.

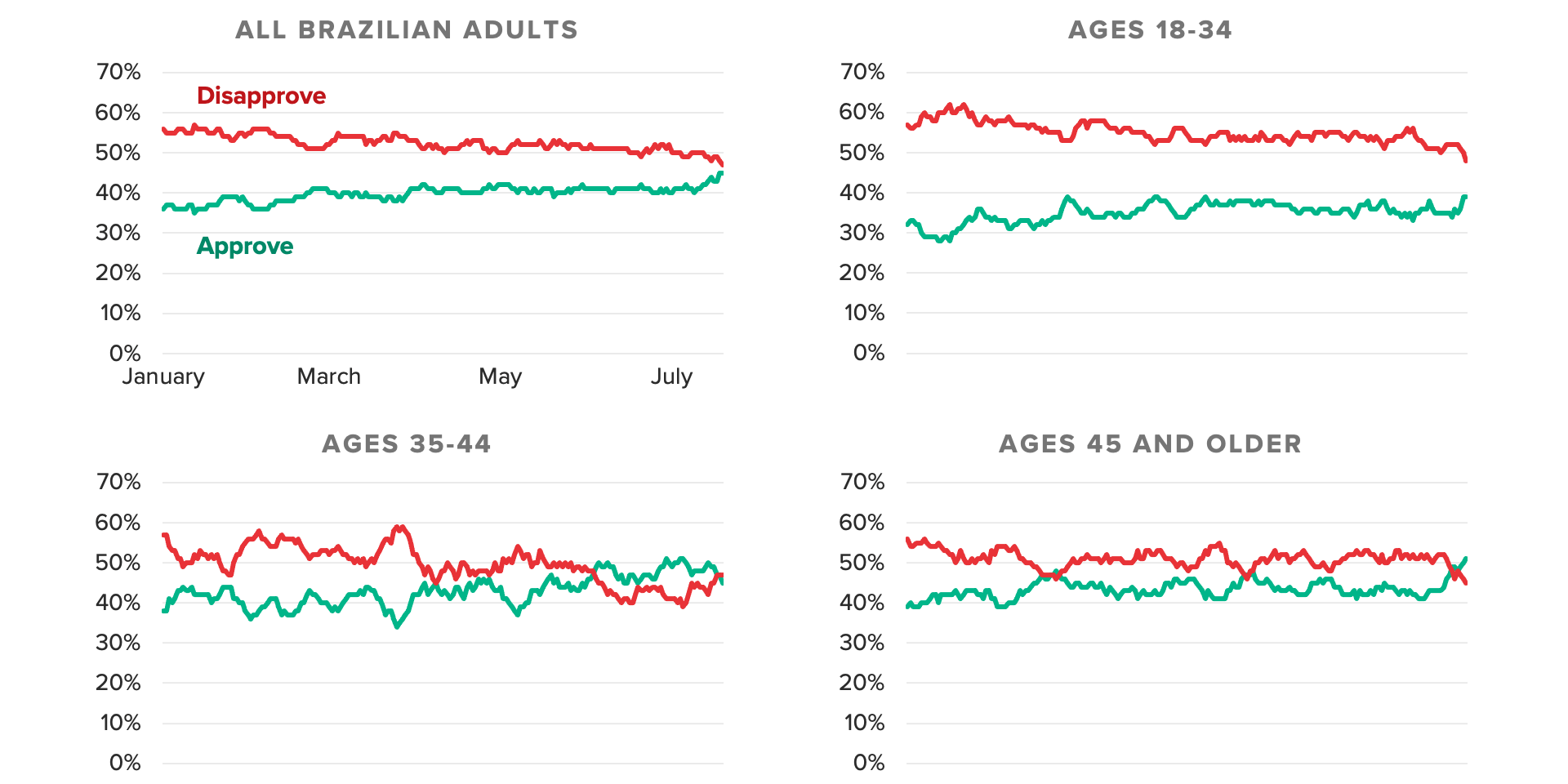

Bolsonaro’s Approval Rating Has Edged Up, Leaving Brazilians Sharply Divided

At 43%, Bolsonaro’s job approval rating remains higher than the vast majority of his peers on Morning Consult’s Global leader approval tracking, often by a double-digit margin. Unlike most world leaders, he has also been steadily gaining in approval this year.

Da Silva, for his part, doesn’t seem to be taking victory for granted, focusing on assembling a broad coalition by appealing to centrists and women worried by Bolsonaro’s attacks on institutions and often flagrant misogyny — both to earn votes and to decrease the likely effectiveness of an attempted coup. Fiona Macaulay, a professor at the University of Bradford’s School of Social Sciences who specializes in Brazilian politics, says it’s old hat for him.

“Lula in the past has been very adept at keeping institutions on his side, even to criticisms of his base on the left who said, ‘Why are you not investigating the military for crimes under the 1964-1985 dictatorship? Why are you sucking up to evangelicals?’” Macaulay said. “He will do whatever is necessary and the man’s skills of conflict resolution and negotiation are extraordinary.”

Those people skills made da Silva a welcome guest abroad during his time in office, with former U.S. President Barack Obama at one point even labeling him “the most popular politician on Earth.”

Heloisa Pait, a sociologist at São Paolo State University, said that while da Silva hasn’t focused much on foreign policy in this election campaign so far given its low salience for Brazilian voters, she would expect him to pick up where he left off in 2010.

She said “it’s going to be a conservative foreign policy in the sense of going back to the roots of Brazilian diplomacy: resilient, very pragmatic, focused on trade and attracting investments and asking for monetary support for certain problems, particularly environmental degradation.”

But Pait said da Silva’s likely prioritization of improved relations with the United States and Europe would come up against a dramatically different geopolitical landscape. With the war in Ukraine and Washington’s increased focus on containing Beijing, da Silva would have to contend with a more precarious balancing act than when he previously also led Brazil’s outreach to China and Russia as fellow emerging economies through the “BRICS” format.

But perhaps the biggest shift from Lula’s first term has been the increased environmental degradation in Brazil, which means traditional models of foreign investment may actually hurt the country over the long term. Brazil’s famed “lungs of the world,” the Amazon rainforest, every month loses over 650 square kilometers of forest — a little less than the total land area of New York City — to loggers, miners and ranchers serving global demand for the country’s premium beef, lumber and minerals.

“If we continue the same way we have approached development in the last 50 to 70 years, it will result in the destruction of the Amazon, and we cannot possibly accept that,” said Milani. “Integrating these environmental challenges into a refurbished development model that is at the same time economically viable will be one of the main challenges Lula would face after winning the elections.”

Matthew Kendrick previously worked at Morning Consult as a data reporter covering geopolitics and foreign affairs.