Chile’s 36-Year-Old President Promised Change. Now Some Are Worried About What That Means

Key Takeaways

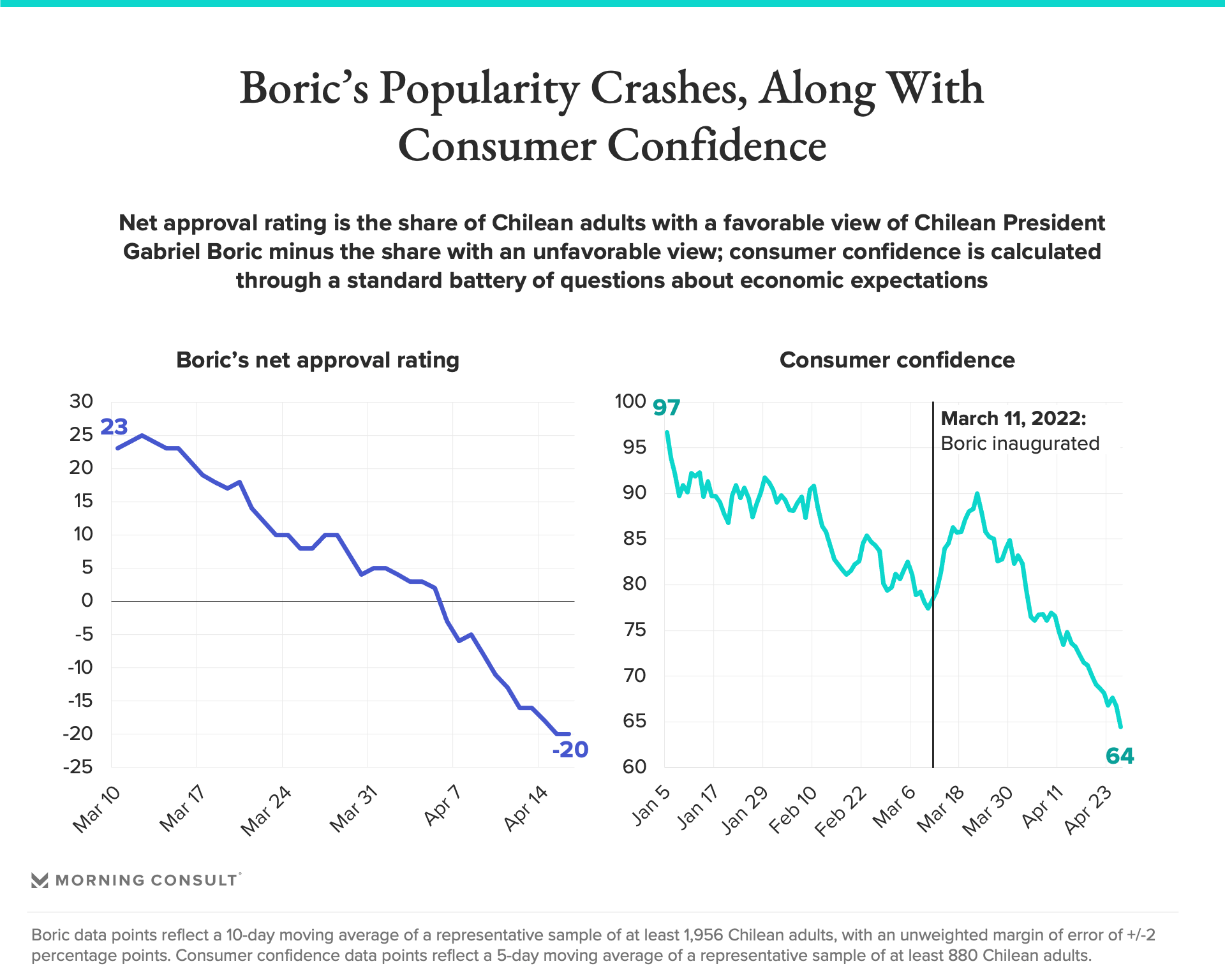

Chilean President Gabriel Boric started his first term in March with the backing of 51% of Chileans, but after just six weeks in office, that is down to 35%, while the proportion of Chileans who disapprove of his job performance has gone from 28% to 55%.

Boric also faces a decline in consumer confidence, as well as annual inflation approaching double digits and grim economic growth forecasts.

However, it’s the ongoing rewrite of Chile’s constitution, which will be put to a ballot in September, that makes the situation facing Boric particularly treacherous.

After three years of often violent street protests that grew out of decades of rising inequality, Gabriel Boric epitomized the hopes of many Chileans for a more fair and inclusive society when he was elected president on a staunchly left-wing platform in December. But just six weeks after his inauguration, meeting those hopes is proving painful — and the 36-year-old president now has his back up against the wall.

Boric’s approval rating is down 16 percentage points since his March 11 inauguration, with disapproval among Chilean adults up 27 points over the same six-week period. Simultaneously, the spike in consumer confidence in Chile that accompanied his inauguration has evaporated, with Chileans smarting from high inflation and grim growth prospects.

“Honeymoons are very short now,” said Maria Victoria Murillo, director of the Institute for Latin American Studies at Columbia University. “Voters had high expectations in Chile; they wanted to see improvements in their lives and competence in government.”

The speed of the new Chilean president’s decline has nevertheless been a surprise to many — even if it fits with broader regional trends, according to Brian Winter, editor-in-chief of Americas Quarterly and the vice president for policy at Americas Society/Council of the Americas.

“Latin America and the Western world in general are full of unpopular presidents right now because of inflation and slow economies — the post-COVID scenario,” Winter said, adding that Boric’s approval rating is about more than just the economy.

He pointed to the southern Araucanía region, where the indigenous Mapuche people have struggled to preserve their culture and autonomy for centuries, and where some confrontations have resulted in deadly violence in recent years. Boric dispatched Interior Minister Izkia Siches for negotiations with them early after his inauguration, having emphasized the rights of indigenous people in his campaign. Instead, Siches, who declined an armed escort, ended up fleeing the area after being confronted by armed men who fired into the air.

“The administration needed to show right away that they knew what they were doing,” Winter said, “and instead the first impression that many Chileans have after the Siches incident is one of an inexperienced government, whose ideology is clashing with reality.”

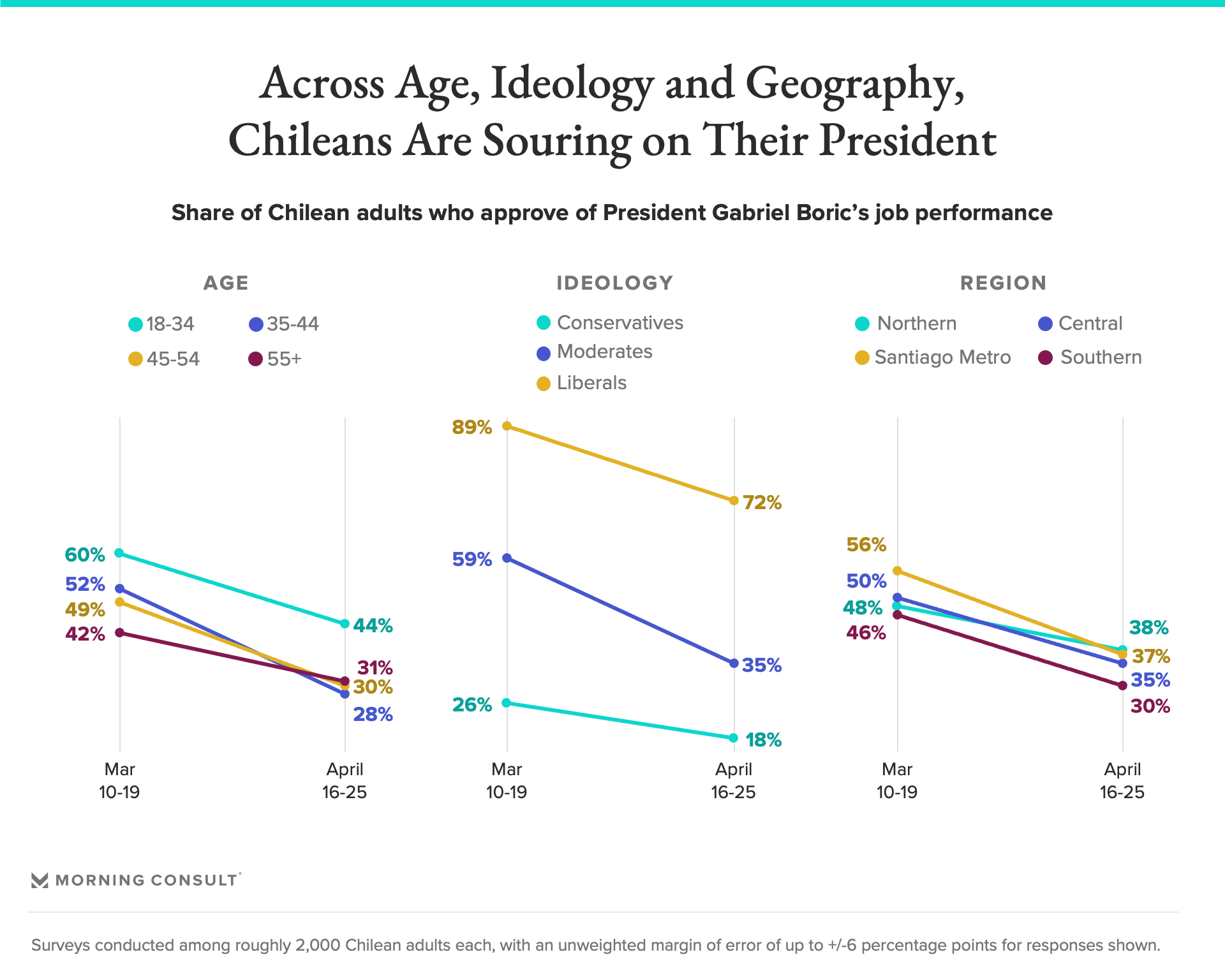

Approval of Boric is on the decline no matter how you slice up the data, with people of all ages, ideological backgrounds and regions appearing to have lost faith in him. But the image of political inexperience is hitting him particularly hard with the group that assured his victory over a far-right candidate last year: moderates.

“For many of the moderates, there's a sense that the inexperience of the new generation could cost the country dearly,” said Francisco González, a professor of Latin American politics at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

González said many in Chile had hoped the rise of Boric, a leader in the widespread student protests against inequality a decade ago, would help cap a period of relative instability for the country.

“But rather than ending unrest, we still have open violence at protests, and a trucker’s strike, and we don’t have migration under control, and it looks like the government and Mapuches could end up fighting,” he said. “Moderates feel afraid.”

If Boric’s new government looks like it’s powerless to steer the ship of state, that’s because it is, at least for the moment, said Marco Moreno, director of the School of Government and Communications at Chile’s Universidad Central in Santiago.

“The government has been unable to control the political agenda because in fact other actors are much more influential on the issues of the day and have left the executive unable to focus on its political priorities,” he said, noting the unusual current legislative arrangements.

Boric’s party, Convergencia Social, controls no seats in Chile’s Senate and just 10 seats in the lower house, making it the third-largest member of the governing coalition. To complicate matters further, a separate body, elected last year to write a new constitution for Chile, controls what is effectively a soft veto over the president.

“Boric cannot really carry out or implement a legislative agenda because everything is really in the hands of the Constitutional Convention,” said Patricio Navia, professor in the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University. “He cannot introduce reforms because if the convention does not like it, they can add text into the draft constitution to undo them.”

Crafting a new constitution

The Constitutional Convention, which was championed by Boric to rework the current document dating back to dictator Augusto Pinochet, has created its own headaches.

The 154-member body represents “a snapshot of the reality of that particularly extraordinary moment when they were elected, with the social outburst beginning in 2019 followed by a pandemic in 2020 and 2021, when people wanted change,” according to Moreno.

But some of the more radical ideas emerging from the group, including Bolivian-style plurinationality, devolving autonomy from Santiago to Chile’s regional governments and enshrining social rights alongside individual rights, have many Chileans fearing the extent of the changes ahead of them.

Chilean pollster Cadem found that as of last month, 46% of Chileans say they plan to reject the new constitution when it is put up for referendum on Sept. 4, compared to 40% who plan to vote in favor. But according to NYU’s Navia, it’s too early to stick a fork in it.

“Those polls currently reflect rejection of what the Constitutional Convention is doing, but not opposition to the new constitution, because the text of the new constitution is not yet out,” he said. “I think it’s going to be so long and full of political presents for everyone that it will eventually pass.”

He compared the Chilean people to parents who may not always be thrilled with their child’s spouse, but will adore the grandchildren once they arrive.

Birthing pains

The legitimacy of Chile’s constitution has always been tenuous, as it was originally approved in 1980 under Pinochet’s military regime, which violently seized power with backing from the United States in 1973.

If the new constitution passes, it will not immediately go into effect, and Boric will have to hammer out its implementation in a process that could take years. The margin of the vote will play a major role as well, as a close passage could detract from the perceived legitimacy of the document. That would make the next steps all the more difficult and has the potential to set off a cycle of destabilizing constitutional revisions.

“In Latin America, people think that constitutions fix things, and that's why Latin America has the world record on new constitutions; we produce new constitutions all the time,” said Navia. “The fact that Latin America remains highly unequal and grows less than average in the world means that new constitutions are not panaceas.”

Still, Boric has a lot riding on his ability to win voters over to a new constitution, having tied his political life so closely to reworking it.

“If the constitution is rejected, Boric will be a lame duck for three years,” Navia said.

Despite the dissatisfaction surrounding Boric’s failure to rapidly reform Chilean society, Moreno said uncertainty is normal during a period of flux.

“We are in the moment of partum, before new life is fully born, which is stressful for any creature, and I expect we will have a few years in which Chile is in the process of stabilizing its institutions,” he said. “I know people outside of Chile are concerned about what they see happening here, but the country is not paralyzed; it is functioning and addressing its own problems.”

Matthew Kendrick previously worked at Morning Consult as a data reporter covering geopolitics and foreign affairs.