Unlike Chile’s Boric, Colombia’s Petro Is Off to an AMLO-Like Start. Can He Maintain It?

Key Takeaways

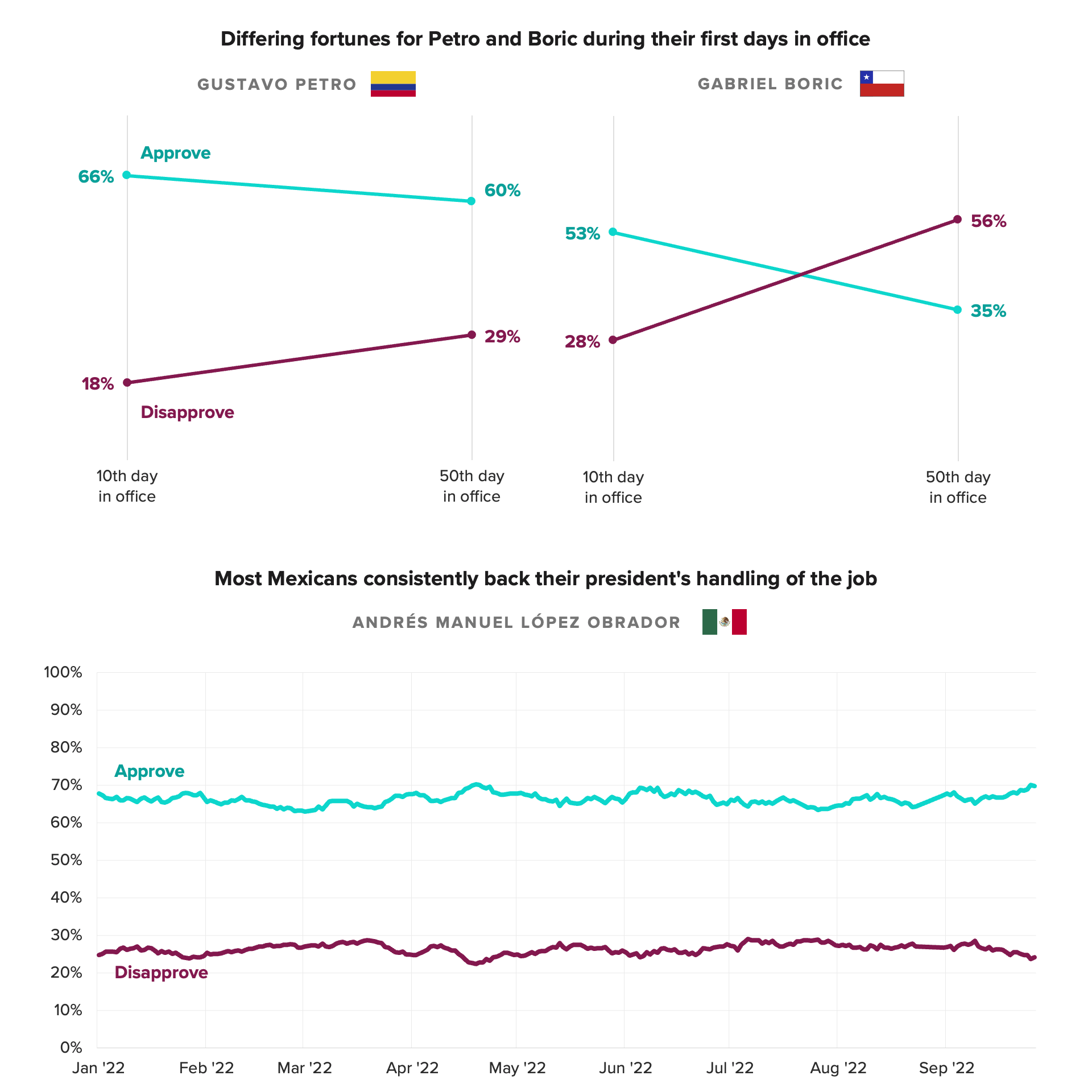

60% of Colombians approve of President Gustavo Petro seven weeks into his term, a much stronger position than that of fellow leftist leader and relative newcomer Gabriel Boric of Chile at a similar point in office.

Petro’s charisma and image as a Colombian everyman may help keep him in high standing among his constituents, just as that persona has helped Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador overcome substantial criticism.

Regardless of how Colombians see Petro, his ambitions conflict directly with ideology and policy in Washington, which threatens to rupture the close relationship if neither side can find a path toward pragmatic cooperation.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro is having quite a honeymoon period, with approval peaking at 70% during the first six weeks of his term. However, the success or failure of his attempts to reshape key social and political paradigms in Colombia will determine whether, like Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, his popularity endures or, like Chilean President Gabriel Boric, initial aplomb fades swiftly when the rubber meets the road.

Petro Has Avoided a Boric-Like Crash So Far, but Can He Match AMLO’s Consistent Popularity?

Petro is currently more popular than all but two leaders in Morning Consult’s Global Leader Approval tracker, a bit of a surprise given that he barely cleared 50% of the vote during the presidential election in June. Then again, Colombia is the most unequal country in South America after Suriname, according to the World Bank, and Petro has proposed major changes to the tax code, health care system and pension plans that could help ordinary Colombians partake more in the prosperity of the nation.

But Petro is biting off a lot more than that. He has proposed an overhaul of environmental policy, the end of drug war tactics that unduly affect the poor, the continuation of the 2016 peace process with armed paramilitaries and — most concerning for U.S. officials — the normalization of relations with Venezuela.

If the protests already emerging against his proposed tax reforms are anything to judge by, Petro may be on the precipice of experiencing the kind of slide Boric saw in Chile earlier this year after similar promises of massive social and constitutional change failed to materialize.

“Leaders tend to get an immediate bump in approval ratings. I would check again in, say, three to four weeks, because it looks like his tax reform is being sliced and diced in multiple different directions,” said Cynthia Arnson, distinguished fellow at the Wilson Center’s Latin American Program, which she previously led as director.

Still, Arnson pointed out that, despite often heavily criticized policy, Mexico’s López Obrador retains the approval of the overwhelming majority of his constituents, and taking a page from AMLO’s public relations playbook might be just as effective in Bogotá.

“AMLO has successfully portrayed himself as a president for the poor and the ordinary Mexican who is struggling economically,” said Arnson. “If you just look at the inflation rate for basic household goods in Colombia, it’s sky-high, so anybody who is promising more distributive policies — and to make wealthy people pay for them — is going to earn some popularity.”

A soft touch could make the difference for Petro’s popularity

Few deny that some change is needed in Colombia, including those from the opposite side of the political spectrum as Petro. Former Vice President Francisco Santos, who served under the center-right government of Álvaro Uribe and later as U.S. ambassador under Petro’s predecessor, Iván Duque, said he agrees “totally” with Petro’s effort to eliminate gasoline subsidies.

“The government can get around 40 billion pesos ($8.77 million) of cash to spend on a lot of other priorities; it’s a very responsible decision,” Santos said, cautioning that Petro will have to approach the issue carefully to avoid backlash. “Drivers and truckers are going to be pissed, and he’s going to pay a price, but if he decides to do the policy well and set aside a quarter of the savings to subsidize truckers and public transportation, it will reduce the harm.”

Kent Eaton, professor of politics at the University of California, Santa Cruz who specializes in Colombia, said that Petro’s charismatic, man-of-the-people persona is reminiscent of the personal style that has helped keep López Obrador popular. However, Petro’s Cabinet choices seem to reflect a few lessons learned about when to play the populist card after his assertive tactics during his time as mayor of Bogotá resulted in his removal from office.

“He knows he can’t directly attack the establishment and the bases of his opposition; he has to be smarter than that,” said Eaton. Instead of staffing his administration with ideological firebrands, Petro “picked quite a diverse Cabinet, and particularly his finance minister, José Antonio Ocampo, has a lot of credibility with the finance sector.”

Clashes with Washington seem unavoidable

Clever appointments and targeted policy might blunt some of the criticism from Petro’s domestic rivals and dovetail with proper messaging around his political brand to keep approval ratings high. But the same strategy is unlikely to keep Washington, which vigorously supported the center-right governments that ruled Colombia for two decades, happy.

Since the late 20th century, Colombia has forged arguably the closest ties with the United States of any Latin American country. The partnership has centered on Bogotá’s fight against revolutionary and counter-revolutionary paramilitaries, some of the world’s largest drug cartels and the numerous hybrid organizations that emerged from their nexus. But Petro has a radically different vision for a new approach rooted to a large extent in his former membership in the M-19 guerilla organization, and it’s sure to be a sticky spot when Petro meets with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken today.

“It’s hard to imagine how the United States could reconcile itself with Petro’s frontal attacks on the war on drugs,” said Eaton. “I can’t think of a U.S. policy that has been as sticky despite manifest evidence of failure. It’s immovable regardless of who is in power in Washington, and it really feels like Petro will be a thorn in the side of the U.S. to the extent he is questioning drug policy.”

Arnson of the Wilson Center pointed to a rhetorical flourish Petro made during his address to the U.N. General Assembly contrasting the lethality of cocaine with that of carbon dioxide as exemplifying the disconnect.

“The argument that hydrocarbons are more dangerous than cocaine is just not going to fly in the United States,” she said.

But regardless of the view from Washington, Petro stands to gain domestically by moving away from crop eradication and toward supporting the poor farmers often left out of the legal economy.

“Petro sees the coca farmer as the lowest link in the chain, whereas the real money is made on the streets of Los Angeles or New York,” Arnson said. “He’s reflecting the view of an important rural base represented by his Vice President Francia Márquez, who wants to see development brought to the forgotten corners of Colombia.”

However, Arnson sees an even greater impediment to good U.S. relations in another of Petro’s early moves: the administration’s embrace of normalization with Venezuela. Images of the Colombian ambassador to Caracas joyfully embracing Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro are sure to raise eyebrows, for example.

“It shows a desire to immediately have a friendly relationship, as if there suddenly weren’t any problems with this government that has been accused by the U.N. Human Rights Council of crimes against humanity,” she said.

And unlike the approach to drug policy, the change of tone with regard to Venezuela promises few social or economic benefits.

“The minister of commerce said they will recuperate a big chunk of trade with Venezuela, in the billions of dollars. That’s not going to happen — Venezuela doesn’t have that money,” said former Vice President Santos. “This is only going to help Maduro and criminal organizations along the border.”

Santos said he fears Petro could severely worsen Colombia’s fragile security situation with such moves, particularly if the administration also takes a hands-off approach to militants, adding that increased violence in the urban areas could “be Petro’s biggest downfall.”

But Santos said the United States can’t afford to wash its hands of Colombia, despite what he called Petro’s “anti-American DNA.” Though the United States had little direct role in Petro’s election, failure to prioritize pragmatic cooperation over moral or ideological conflicts would further entrench a cycle of neighborly neglect with long-term consequences for the entire hemisphere.

“The United States has shown it doesn’t give a s--- about Latin America. They should understand that the ideological, political and economic conflicts of the future have a lot to do with the region, and that they neglect it,” he said, though he dismissed notions that U.S. neglect contributed to Petro’s election as ignorant of the domestic political dynamics that played greater roles.

The real risk, according to Santos, is when the United States sacrifices hard-earned influence and soft power to rivals such as China. When Washington fails to engage in a pragmatic relationship with Colombia and places too much pressure on Bogotá over issues like human rights, “China comes in and says, ‘I don’t give a s--- about your human rights.’”

As Petro rolls out his policy agenda, it’s too early to say how a decline in popular support — or conversely, a continuation of his popularity — might shift the particulars of his approaches and their palatability to the United States. But the U.S.-Colombia relationship will remain key to handling drugs, violence and migration throughout the Western Hemisphere, and Washington would do well to adhere to a long-term vision in its relations with Bogotá.

Matthew Kendrick previously worked at Morning Consult as a data reporter covering geopolitics and foreign affairs.