E.U. Energy Integration Could Save Germany From Its Natural Gas Dilemma

Key Takeaways

Germany’s reliance on Russian natural gas and decisions to wind down both coal and nuclear power production in recent years has left the government with few good choices to manage both skyrocketing energy prices and their geopolitical consequences.

Few other European powers are as dependent on Russian gas as Germany, but survey data suggests the spike in prices is making Germans more open to both cooperation with other countries for energy and open to more controversial fuels such as nuclear and coal, even if those aren’t viable options for Germany.

To achieve energy security, experts say Germany must work with the rest of Europe to connect power grids and pipeline networks to move energy and fuel where it is needed and redouble efforts to expand renewable energy production.

Germany’s reliance on Russian natural gas has rendered it particularly vulnerable to Moscow’s weaponization of its energy exports amid the Ukraine war, and with a shift to either nuclear or coal power also out of the question due to their domestic unpopularity, Europe’s largest economy is facing unprecedented concerns about its energy security. Yet Morning Consult surveys show Germans are becoming more open to one possible solution: integrating their energy sector with those of their neighbors, which is precisely what experts say is needed.

A German vulnerability to gas-based coercion has been clear from the start of the war, with Berlin’s Western allies voicing concern about its wherewithal to defend Ukraine from Russia amid threats Moscow would turn off the gas spigots. Berlin has spent decades building a Russian-oriented gas infrastructure, and lacks the underpinning to import a sufficient quantity of gas from other producers while having few alternative domestic energy sources.

That means Berlin’s decisions on energy policy over the coming months will play a key role in the West’s ability to back Ukraine in its war against Russia, and could impact E.U. cohesion, according to Benjamin L. Schmitt, an associate of the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University and a former European energy security adviser for the State Department.

“If the E.U. and NATO writ large are going to support Ukraine robustly, it’s going to require an unprecedented level of E.U. energy unity,” Schmitt said. “It is going to require Berlin to effectively continue to reorient structurally away from Russian energy at a lightning pace to demonstrate to the rest of the bloc that they are serious; that they want to be united.”

Schmitt said the onus fell on Berlin to lead by example after shirking a chance to pursue other energy sources in the wake of Moscow’s 2014 annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region.

“From that time until just a few months ago, Germany took no steps to diversify away from Russian energy dependence, and in fact clung to strategic anchors like the Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines that only increased strategic vulnerability to Russian energy weaponization,” he said.

The good news for Berlin is that its own population, as well as those of the two next largest European economies, have grown increasingly ready to cooperate on energy issues.

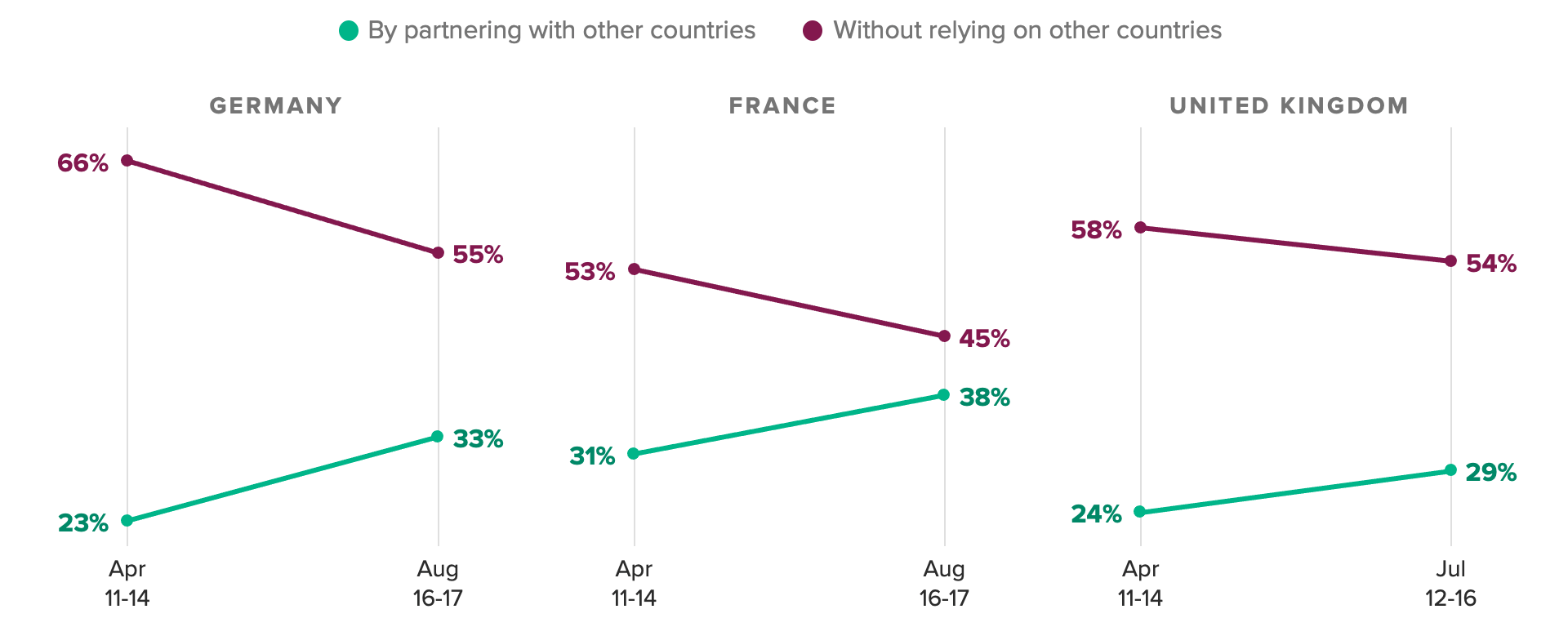

Adults in Europe’s Largest Economies Are Feeling More Cooperative on Energy

According to Morning Consult surveys, the share of Germans who believe they would be better off partnering with other countries for energy security rose 10 percentage points, to 33%, between April and August, while France saw a 7-point increase, to 38%, over the same period. In the United Kingdom, meanwhile, there was a 5-point increase, to 29%, between April and July.

Germany’s conflicting policy decisions cause headaches

While the trends may be moving in a favorable direction, the lion’s share of Europeans still prefer energy independence if they can get it. For most countries on the continent, though, that’s much easier said than done.

The European countries with the largest natural gas reserves besides Russia are Norway and the United Kingdom. Neither is an E.U. member state, and both are also experiencing massive spikes in gas prices despite their geological good fortune.

In Germany, the only major domestic fuel source would be coal — and a particularly dirty form of it at that. Coal fueled the industrial revolution in German lands before the nation unified in the late 19th century and still made up nearly 40% of Germany energy supply in 1990, according to the International Energy Organization.

Berlin aggressively phased out coal plants to meet environmental aims, and by 2020, coal made up just over 15% of Germany’s energy supply. Notably, though, that program coincided with the pursuit of another deeply held German ambition: post-Cold War reunification.

Reintegrating the former East Germany after two generations behind the Iron Curtain by some estimates cost more than $2 trillion between 1990 and 2015 — a burden Germany could not have sustained without cheap energy to fuel industry and heat homes, according to Michael Mosser, an associate professor of international relations at the University of Texas at Austin.

“Germany was constrained by the amount of money they spent on reunification, but bringing East Germany into the fold opened a huge amount of already existing terminals connecting it to the former Soviet Union,” Mosser said. “In the early 2000s, Germany was looking at Russia as a giant gas station and a way for them to get this easy supply of energy they needed.”

Indeed, in her first interview after the Ukraine war broke out, former Chancellor Angela Merkel, said she had “nothing to apologize for” with regard to her legacy with Russia.

The nuclear (non)option

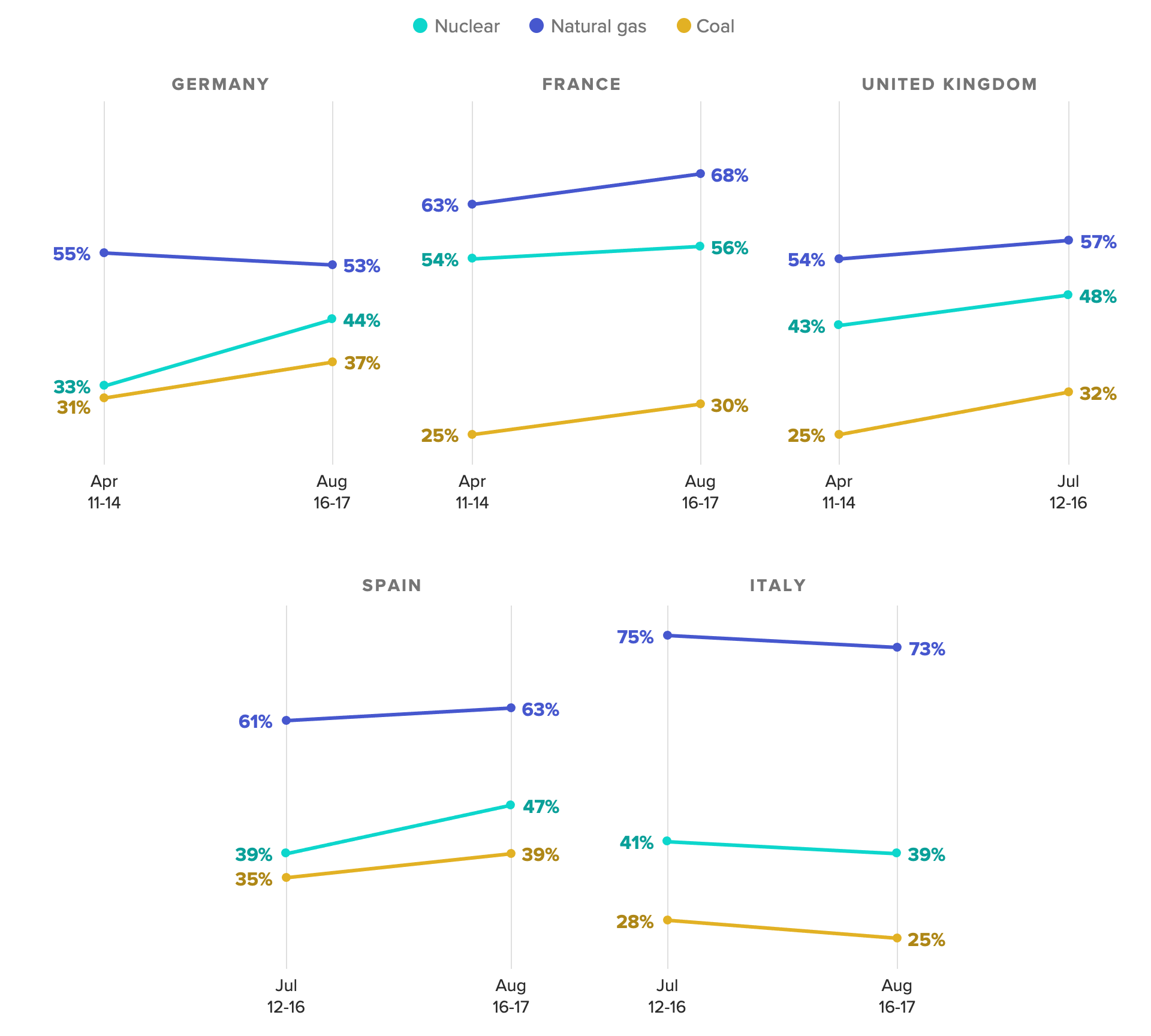

Many Europeans would seemingly agree: Despite high prices and its weaponization by Moscow, natural gas has not seen a major downturn in its favorability across Europe.

Natural gas remains the preferred nonrenewable energy source in Europe’s five largest economies, and its popularity actually improved in France, the United Kingdom and Spain even as prices have risen this summer. In Germany and Italy, favorable views only fell 2 points.

Despite Sky-High Prices, Natural Gas Is Still Most Favored Energy Source in Europe’s Five Largest Economies

Notably, favorable views of nuclear power among Germans rose 11 points, to 44%, between April and August, the biggest increase of any country surveyed, and a remarkable figure in famously nuclear-averse Germany.

The spike in natural gas prices has led to discussion in Germany about extending the life of its last remaining nuclear power plants, particularly as neighboring France has proved better-positioned to weather Russian gas cuts, given that around 40% of its energy comes from nuclear power. However, German economy minister Robert Habeck recently ruled out the option, saying it was not worth reopening the nuclear debate given nuclear skepticism in Germany.

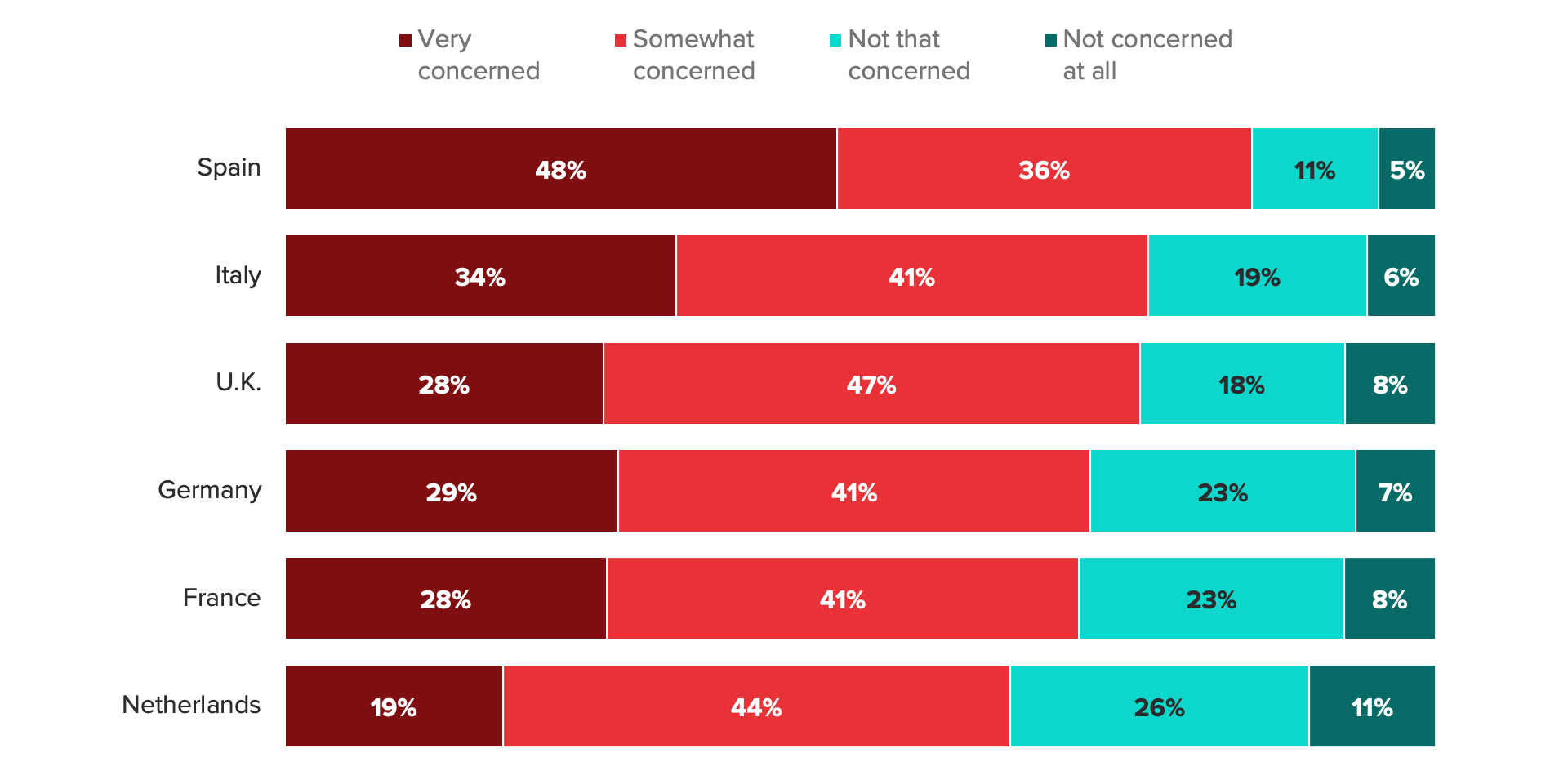

Europeans Are Concerned About the Safety of Nuclear Energy

Even when prompted with information about the safety of nuclear energy, 70% of Germans still say they would be concerned about nuclear accidents if their country were to build more nuclear power plants, making it a political non-starter for Berlin.

Scholz has few good options, but neither do his opponents

With no end in sight to the war in Ukraine, Germans are virtually certain to face high energy prices for the next several years. That’s an unenviable prospect for any world leader, but the silver lining for Scholz is that his opposition can’t credibly claim to have any better solutions.

“The Scholz government can weather one bad winter,” said Mosser, adding that there were few certainties for Germany going forward. “If it is a harsh winter, there is no question the government will be constrained in what it can do. Germany will in many ways be mortgaging the future to get through this winter and possibly the next one as well.”

Arne Jungjohann, political scientist and author of “Energy Democracy: Germany’s Energiewende to Renewables,” gave Scholz credit for moving swiftly to accelerate renewable energy development, which could in the long term help keep Germany on track to meet its climate goals and, in the shorter term, help compensate for the loss of natural gas from Russia.

“Our government does not just want to replace energy imports from Russia, but they want to shift toward renewables and greater efficiency,” Jungjohann said, citing recent legislation designed to cut down barriers to renewable energy projects. “This is probably the fastest-acting government that Germany has seen in transitioning to a renewable energy-based system, and yet we don’t hear much about it.”

In the meantime, though, natural gas remains Germany’s most feasible fuel source, and that leaves one path forward: integrating its existing energy networks with the rest of Europe.

In 2014, the European Union began its “Energy Union” program, which was meant to do the unsexy but crucial work of connecting Europe’s disparate power grids, building a collective energy market and establishing a secure energy supply line for the bloc. Among the ideas being explored are a pipeline connecting Spain’s and Portugal’s gas networks to Italy’s — and from there to Germany’s — potentially opening many more avenues for gas imports and sharing.

“Unlocking the Iberian Peninsula in terms of its massive import capacity could make a big, big difference, and this interconnector could be built within the next several months,” Schmitt said, explaining that access to Spain’s and Portugal’s liquefied natural gas terminals would give Germany greater access to gas from Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Australia. “That's incredibly important, and frankly, this is the sort of step that should have already been taken.”

Ultimately, those are the kinds of steps that will help Germany avoid becoming the weak link that breaks the European front against Russian aggression, Schmitt said.

“As Europe becomes more united on alternative sources, routes and fuel types, it becomes easier to maintain overall unity, so that there isn’t a political decision that has to be made by European governments between their own energy security and their support for Ukraine,” he said. “That is what Vladimir Putin is hoping for, and that is what absolutely cannot be allowed to happen.”

Matthew Kendrick previously worked at Morning Consult as a data reporter covering geopolitics and foreign affairs.