As China Reopens, Its Labor Force Is Feeling the Strain

Key Takeaways

In the last few years, “involution” has become a buzzword describing China’s hyper-competitive work culture and crushing labor expectations, especially among younger white-collar workers. Awareness and acceptance of the concept have led to the growth of more controversial ideas, including the notion of “lying flat” — opting out of the workforce or giving up on the idea of advancement altogether.

Our data shows that public awareness of involution has grown amid China’s fraught economic recovery, suggesting the country’s labor force is feeling added pressure.

In parallel, two-thirds of Chinese adults now see signs of involution in the country’s economy and society, up 6 percentage points since Morning Consult first surveyed on the issue in late 2022.

While public sentiment on this front paints a picture of a workforce under stress, it also provides an opening for Western companies doing business in China to make inroads with local employees — and potentially improve their reputation in the eyes of government officials — as the Chinese Communist Party works to overcome challenging economic conditions in the months ahead and reshape the domestic economy for the long term.

Sign up to get our analysis and data on how business, politics and economics intersect around the world.

In 2020, a once-obscure academic term, “involution,” began taking the Chinese internet by storm. The anthropologist Clifford Geertz first used involution to describe societies in which diminishing productive returns placed ever-growing and ultimately unsustainable demands on agricultural workers. In China, the term was originally used to describe the plight of middle-class mothers struggling to juggle career expectations and their children’s increasingly competitive and complex educational lives. It has since gained traction with younger white-collar workers who felt worn-out by the competitive demands of China’s 996 work culture — an allusion to work hours from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week.

Involution’s far more controversial cousin is “lying flat,” whereby stressed workers choose to opt out of the labor force or otherwise reject the goal of economic advancement. The term has attracted more attention from the Chinese government due to the risks it poses to the country’s developmental trajectory. Whereas the government has routinely censored public discussion of lying flat, it has allowed discussion of involution to persist.

Awareness of involution has grown amid China’s stalled reopening

In late November 2022, when Morning Consult first surveyed Chinese adults on their awareness and understanding of involution, 85% of respondents said they were familiar with the word, but less than half claimed to clearly understand its definition.

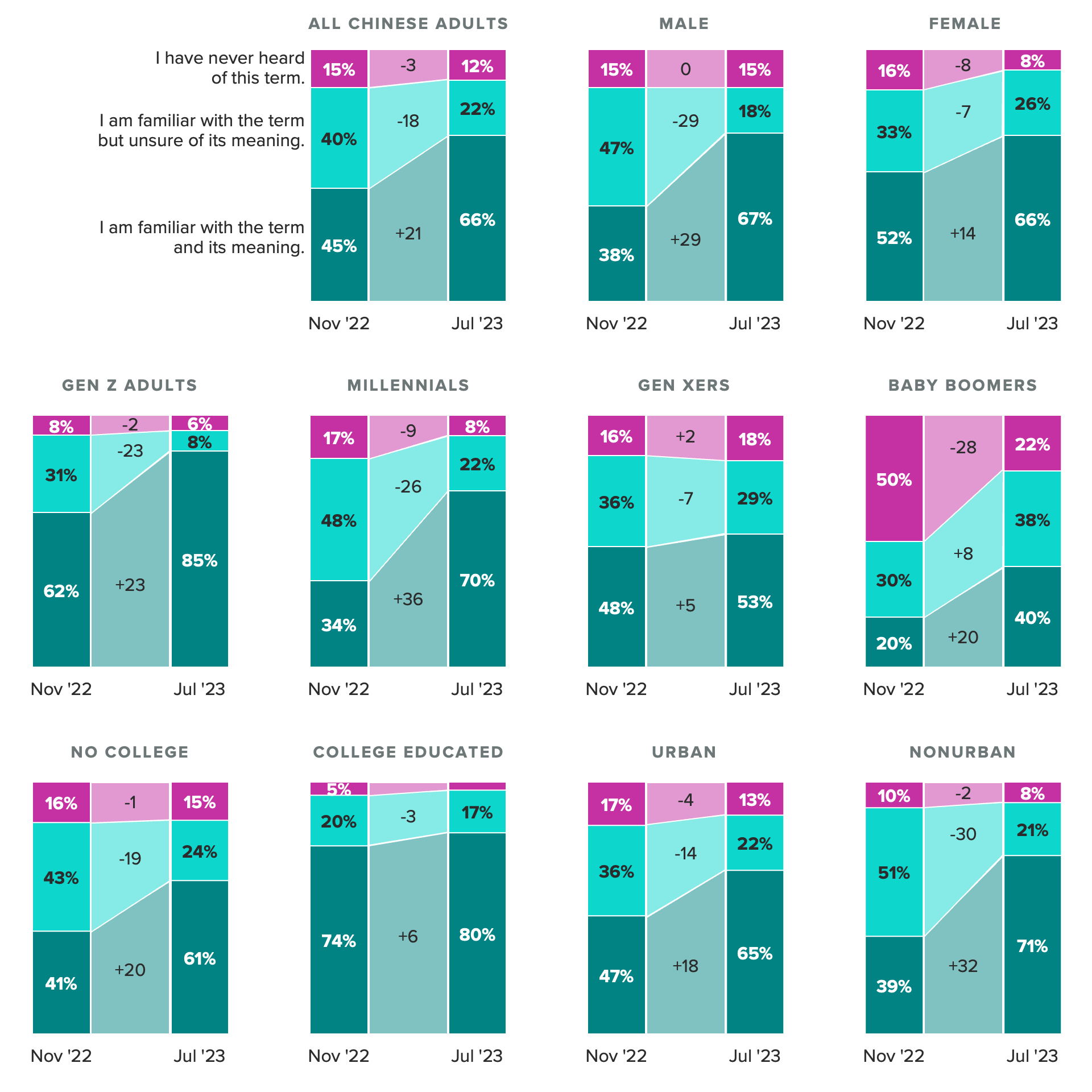

Awareness and Understanding of Involution Have Grown in Recent Months

At that time, women were 14 percentage points more likely than men to say they understood the term, possibly speaking to its original Chinese usage. Unsurprisingly, Gen Z adults reported the greatest familiarity with the term, by a double-digit margin.

Roughly seven months after China’s reopening, we again surveyed a representative sample of Chinese adults on their awareness of involution and found that it had risen. Roughly two-thirds of Chinese adults now say they are familiar with involution and understand its meaning, up 21 points from November 2022.

We observe a consistent increase in awareness across virtually every demographic, suggesting a broadening of awareness. Two-thirds of Chinese men now say they fully understand the term, up nearly 30 points from November 2022. The share of those lacking a college education who said the same, meanwhile, rose 20 points, surpassing a majority, while the share of nonurban residents rose a staggering 32 points, indicating that awareness of the term has spread beyond educated, urban elites.

More nonurban adults now say they understand the term than city dwellers (71% versus 65%). Understanding of involution has also spread across generational lines: Baby boomers are now the only cohort where less than a majority understand the concept (40%), though awareness has seen major growth even among this group, with more than three-quarters (78%) saying they have at least heard of the term.

Those who understand involution think the term applies to today’s China

Growing public understanding of involution is important: Those who say they understand the term are the most likely to describe it as relevant to China today (79%), a percentage that held constant across both waves of our survey.

A Stalled Recovery Has Chinese Adults More Convinced That Their Society Is Involuted

Meanwhile, two-thirds of Chinese adults overall now see China’s economy and society as involuted, up 6 points from late November 2022. The trend again largely holds steady across key demographics. Women remain more likely to view their country as involuted than men, while Gen Z adults are more likely to say so than other generational cohorts, with more than three-quarters (78%) describing China’s economy and society as exhibiting involution. Yet a majority of every generational cohort now describes China as involuted, including 63% of baby boomers, up 19 points from November 2022.

Specific demographics at scale: Surveying thousands of consumers around the world every day powers our ability to examine and analyze perceptions and habits of more specific demographics at scale, like those featured here.

Why it matters: Leaders need a better understanding of their audiences when making key decisions. Our comprehensive approach to understanding audience profiles complements the “who” of demographics and the “what” of behavioral data with critical insights and analysis on the “why.”

Geographically, those in China’s more developed eastern region are more likely to say the country is experiencing involution (71%), speaking to the effects of the stalled economic recovery. China’s major cities, mostly concentrated along its eastern seaboard, have struggled with debt issues related to pandemic measures, putting strain on their labor markets and ratcheting up competitive pressures. Relative to late 2022, respondents in this region were 8 points more likely to view China as involuted in July, seven months after reopening. Yet similar trends can be seen in the country’s hinterlands: 63% of adults in central or western China see the country as involuted (up 4 points). And while two-thirds of urban residents say China is experiencing involution, the share living in nonurban areas has now reached 71%, up 12 points.

Sorting by educational attainment, the share of college-educated respondents who said China is involuted held steady at 77% across this time period, while the share among those lacking a college education rose 5 points to 64%. Involution first gained broader traction to describe the plight of elite students and white-collar office workers, especially those in the tech industry, so it makes sense that there would still be higher acknowledgement among the highly educated. Yet the rise in those without a college education shows how the concept has spread to broader segments of the labor market.

Meanwhile, the wealthiest respondents — defined as those from households earning at least 50,000 yuan ($6,855) per month — were the most likely of any income bracket to describe China as involuted at 77%. This share saw a 14-point rise relative to 2022, the largest of any income group. These findings should be interpreted cautiously given the small sample size for this group. But the trend is striking and may similarly reflect growing frustrations among the highest-paid tech workers. It could also speak to the strain on private entrepreneurs, a critical bellwether of economic recovery and a group that has been struggling to come to terms with Xi Jinping’s growing regulatory scrutiny of the private sector.

The high-income group — whose salaries put them on par with the Western middle class — are the next likeliest to view China as involuted, with 7 out of 10 holding this view, a 7-point rise from November 2022. At the same time, the lowest-earning respondents saw almost as dramatic an increase (13 points) as the highest-earning ones: Two-thirds of the former group now say China is feeling the effects of involution. Middle-income adults held steady, with 63% seeing signs of involution. While Chinese adults with greater social and financial capital tend to be more convinced that their country is involuted, growing sentiment across income brackets speaks to broad frustrations affecting every level of China’s workforce.

How foreign businesses could benefit

Growing awareness of involution, which points to a rising risk of burnout among the Chinese labor force, is also indicative of public frustrations with a private sector that’s placing ever greater demands on workers. This may cause more workers to question their values surrounding work-life balance. While the Chinese Communist Party may worry about the challenge this could present to its long-standing commitment to development at both the individual and national level, it is unlikely that this shift in awareness will pose a direct threat to party rule, even if it speaks to broader social frustrations of which the party is wary.

Rather, growing conviction that China is involuted may speak to a gradual evolution in personal conceptions of work-life balance. In the long run, this could even yield benefits for China’s developmental trajectory as the country transitions to a more advanced economy. Indeed, research shows that labor forces with a better work-life balance are often more productive. The Chinese Communist Party has even obliquely recognized this may be true, reflected in its recent attempts to correct course and regulate China’s 996 work culture, albeit with mixed results.

At a time when private businesses (both foreign and domestic) are increasingly under scrutiny by the Chinese government, trends in public sentiment on involution provide opportunities for corporations to curry favor with the public and the government alike.

While frustrations over involution could speak to burnout and even spur some workers to leave the workforce, they may also simply suggest that Chinese workers — especially younger, college-educated ones — are increasingly picky about their jobs and what they expect from them going forward. At the same time, China is facing an employment crisis that is falling particularly hard on the shoulders of younger workers, and the public continues to crave foreign investment (and investment that creates jobs, specifically). When it comes to public opinion about involution, this potentially points more in the direction of Chinese adults becoming selective about their jobs than to workforce exits.

China is no longer the world’s factory. As the country moves up the value chain, there are growing public expectations of changing employment norms. Western companies that can provide these sorts of jobs along with a better work-life balance could win reputational plaudits that help offset the costs of more generous employment policies. Conversely, those that do not could attract the ire of workers who are already fed-up with crushing labor expectations and enabled by a Chinese government whose relationship with the private sector, and especially foreign companies, is currently fraught.

Scott Moskowitz is senior analyst for the Asia-Pacific region at Morning Consult, where he leads geopolitical analysis of China and broader regional issues. Scott holds a Ph.D. in sociology from Princeton University and has years of experience working in and conducting Mandarin-language research on China, with an emphasis on the politics of economic development and consumerism. Follow him on Twitter @ScottyMoskowitz. Interested in connecting with Scott to discuss his analysis or for a media engagement or speaking opportunity? Email [email protected].

Related content

In 2023, Chinese Consumers Are Doing What They Do Best: Saving

How Chinese Study Abroad Preferences Have Changed Since the Pandemic