Disillusionment, More Than Ideology, Is Driving Europeans to Right-Wing Parties

Key Takeaways

Over the last two years, equal numbers of E.U. countries where we survey have seen ideological shifts left and right. These shifts have been reflected in recent election outcomes in the Netherlands, Poland and Spain.

Apart from the Netherlands and Poland, the shares of adults claiming extreme far-right ideology haven’t risen much. Neither have extreme views in general.

But far-right parties are overperforming relative to the shares of adults who say they hold far-right views. In most of the places where these parties appear to be doing particularly well, pluralities say that no political party closely reflects their own views. This points to disillusionment, rather than ideology, as a main driver of far-right success.

In the runup to E.U. parliamentary and national elections across the continent, mainstream and far-right parties will seek to woo these disillusioned voters: the far-right by trying to present a more palatable image to them; the mainstream parties by co-opting far-right narratives around immigration and cost of living.

While right-wing blocs in the E.U. Parliament will probably gain some seats, the nature of the malaise driving support for far-right parties in several E.U. countries makes it unlikely we will see an overwhelming wave of new far-right parliamentarians cooperating to challenge broad swathes of policy. But national elections across the continent present another avenue for voters to express their dissatisfaction at the ballot box.

Is Europe shifting to the political right? This question pervades discourse about the upcoming year of elections on the continent, especially in light of E.U. Parliament elections in June. The answer from our daily surveys of Europeans in 12 of the largest E.U. countries is a qualified yes.

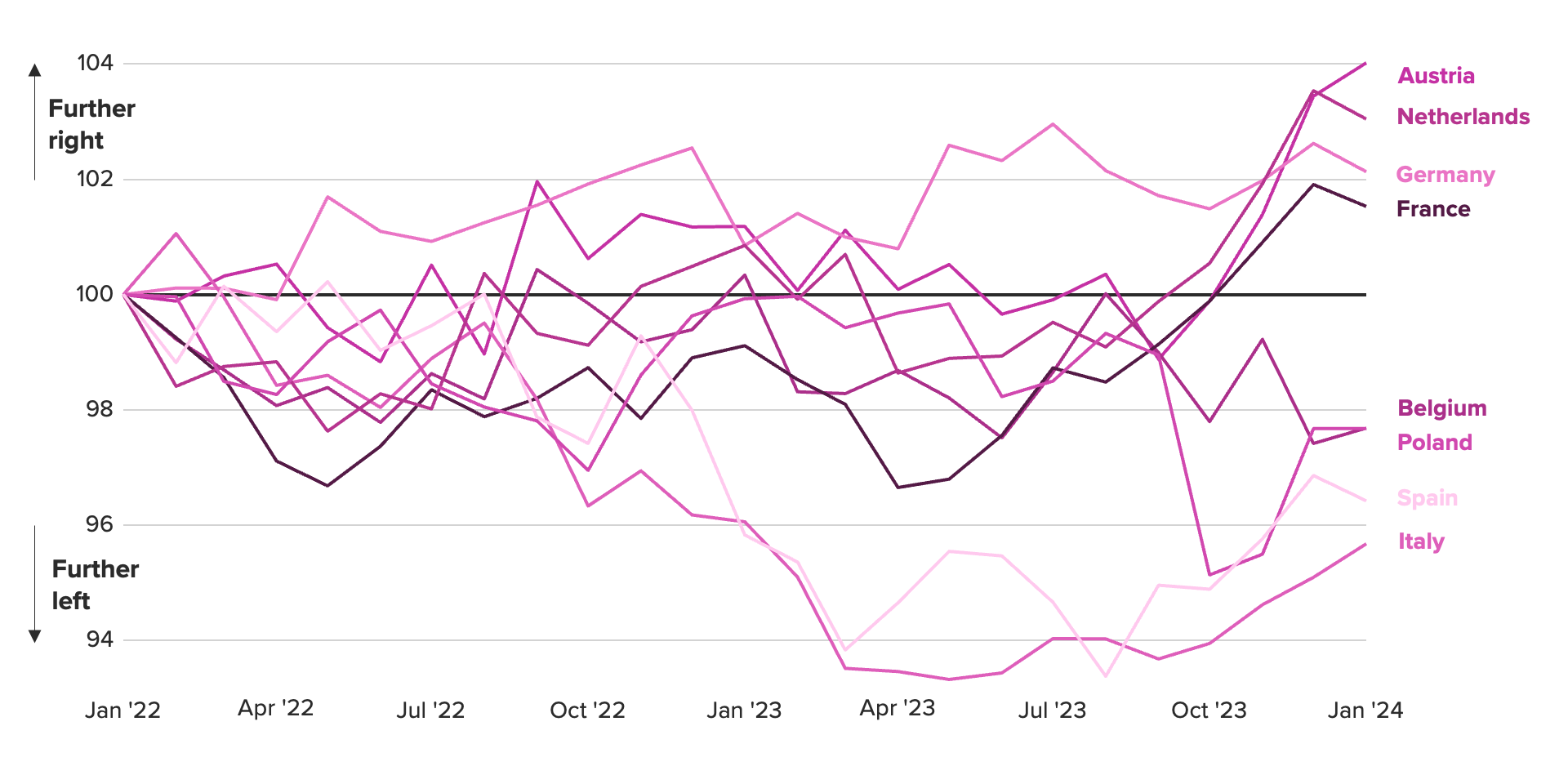

Assessing ideological trends over time

Morning Consult surveys daily in the following E.U. countries on an array of economic and political questions: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain and Sweden. Respondents characterize themselves on a 7-point scale of political ideology ranging from 1 (far-left) to 7 (far-right). While interpreting absolute values of political ideology can be difficult due to complicated conceptualization of political identity, the relative change in right-left identification can be plotted over time and then compared cross-country. In the figure below, we take a weighted mean of responses on our political ideology scale and index it to January 2022 to show how adults’ political ideology in each country has shifted over the last two years.

Equal Numbers of E.U. Countries Show Rightward and Leftward Trends in Political Ideology

Everybody look left. Everybody look right

Overall, four E.U. countries in our sample noticeably shifted right relative to January 2022, four countries shifted left, and the remaining four countries (not shown in the chart) showed no appreciable change. Austria, the Netherlands, Germany and to a lesser extent France, showed rightward shifts, but notably many of these took place only in the last five months. Belgium, Italy, Poland and Spain clocked slight shifts left over the last two years.

Recent electoral history bears much of the data out. In Spain, fears that Vox would become a junior coalition party with the Popular Party (PP) proved unfounded as the center held in the July 2023 elections. Poland tacked left after eight years of government by the conservative Law and Justice Party. Dutch adults, meanwhile, handed Geert Wilders and his far-right Party for Freedom (PVV) the most seats in the November 2023 elections.

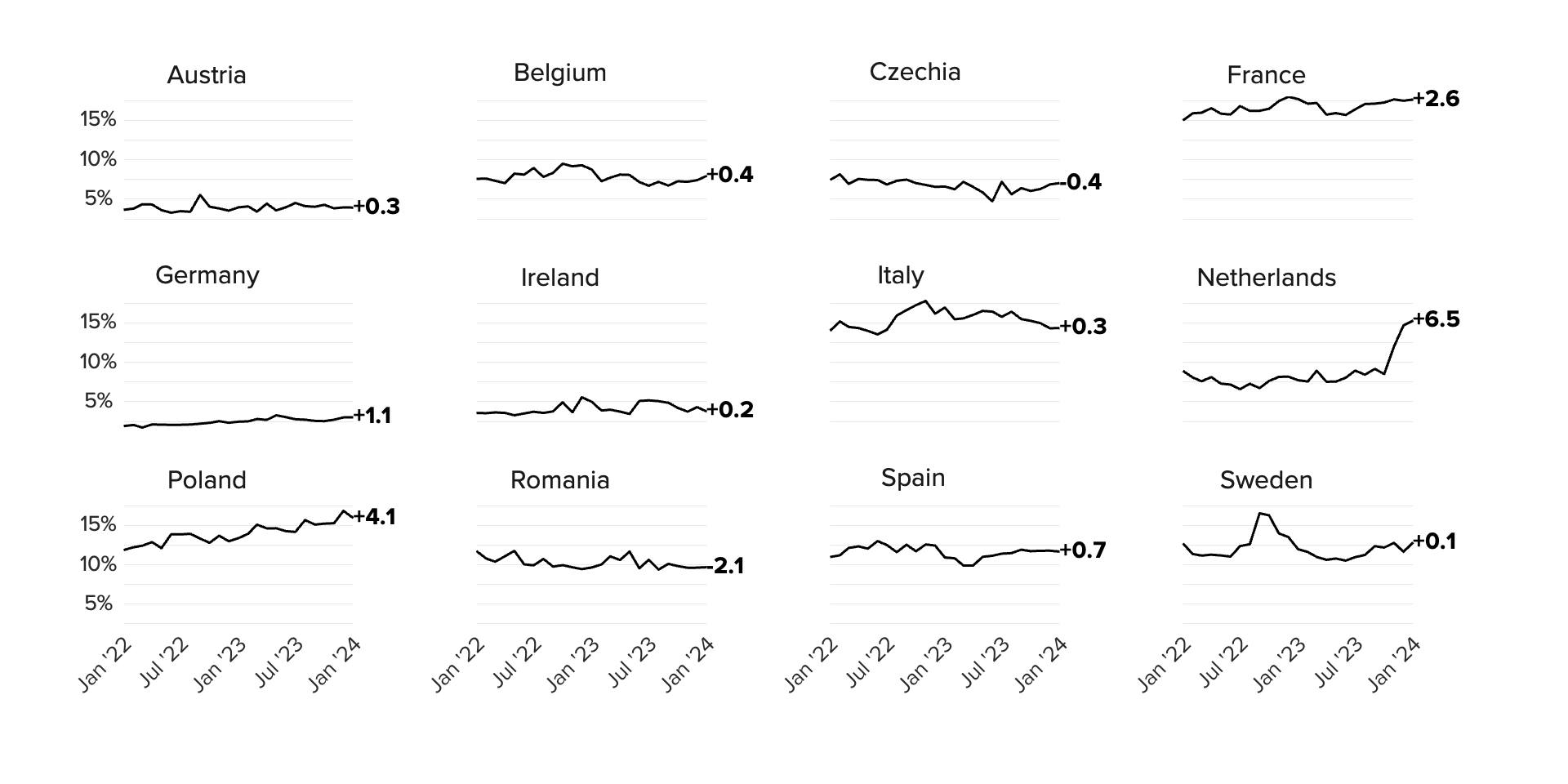

Changes at the far right of the spectrum only partly explain the shifts

We then look only at the percentage of respondents choosing the most extreme right end of the spectrum (seven on the 7-point scale) over time, we see another mixed picture. There was a sharp increase in the share of Dutch adults willing to identify as far-right in the lead-up to those elections, indicating the far end of the spectrum is driving the rightward shift there. Other countries with over a 1 percentage point increase in the share of adults espousing far-right ideology include France and Germany, although the latter is from a very low base, and the former from a rather high one — likely due to strong stigma from Germany’s Nazi history.

Spain, on the other hand, saw its far-right shares holding almost steady. And even more curiously, Poland saw a steady rise in adults claiming far-right ideology at the same time Polish adults said they shifted left overall — an indication of higher political polarization.

Poland and the Netherlands Have Seen the Largest Increases in Adults Claiming Far-Right Ideology since 2022

Polarized Poles

If we then total the shares of respondents who said they were either as far-right or as far-left on the spectrum as possible, Poland and the Netherlands stand out as countries where political ideology has become more extreme in general since January 2022, with right-wing views dominating the trend. In the case of the Netherlands, this polarization is already showing its potential to create instability as government formation talks head into their third month. Poland does not have general elections again until 2027, but this trend will be something to watch as a source of political instability there in the medium term. But importantly, most other E.U. countries have not seen large increases in extreme views.

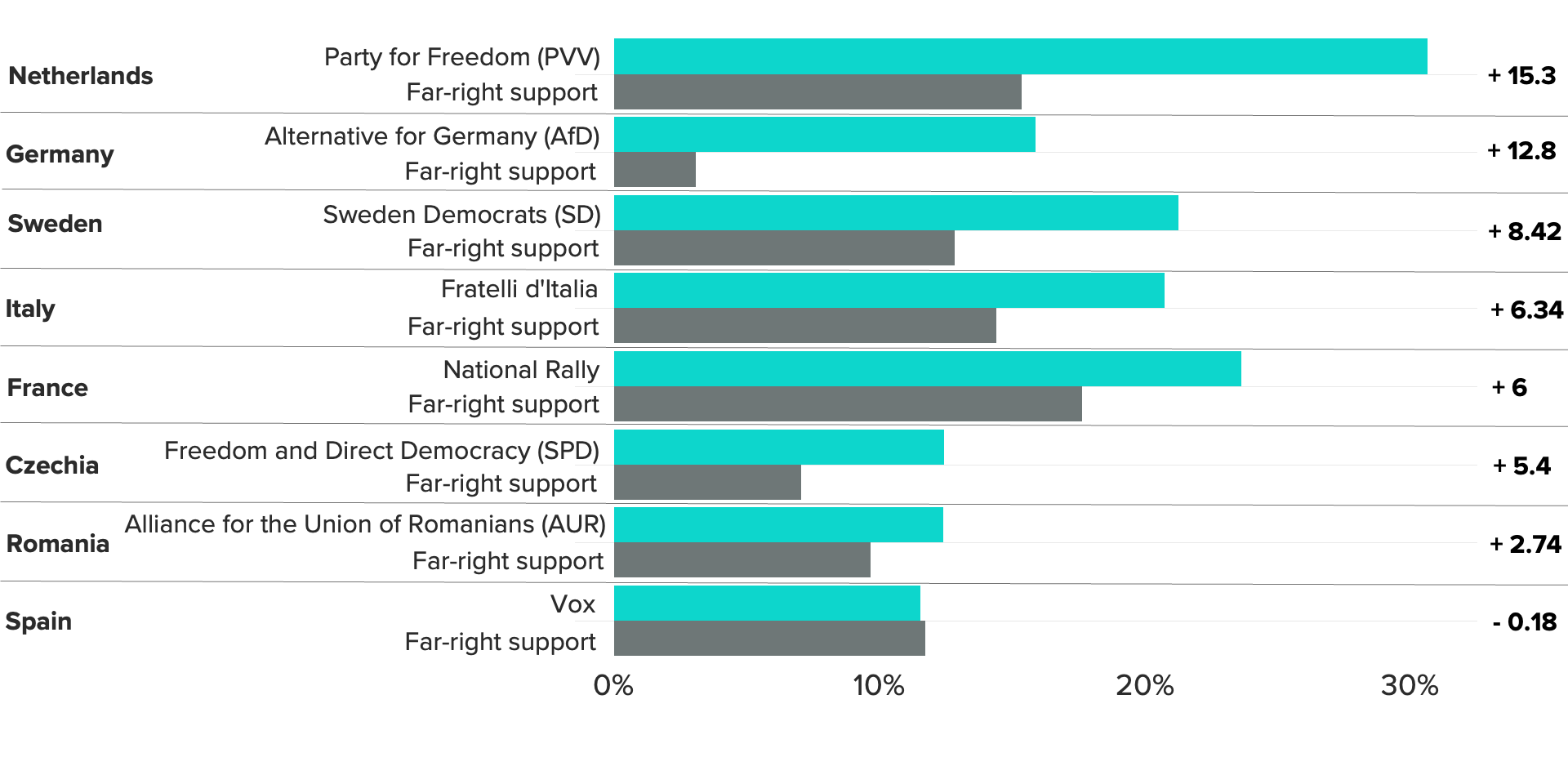

Right-wing parties are gaining support beyond right-wing ideologues

In fact, the shares of adults saying they hold extreme right-wing views on our ideological scale is much lower than the shares saying that a far-right party is “closest to their own views” in a number of key European countries. Right-wing parties are overperforming — gaining support from people who are not themselves far-right ideologues. If we look only at those adults with the furthest right-wing views (a value of 7 on our 7-point scale) and only at far-right parties (rated as 8.5 or higher on a 10-point left-right scale by a political science data provider) we can see where the differences are the largest.

Far-Right Parties Have Appeal Among Non-Right-Wing Populations

We include a far right party in eight E.U. countries where we survey on political party affiliation. In seven out of the eight, those parties are over-performing relative to the share of adults in the same country who actually claim far right ideology. Only in Spain is almost exactly the same share of adults saying they hold far-right views and also supporting the far-right Vox party.

Disagreement or disillusionment?

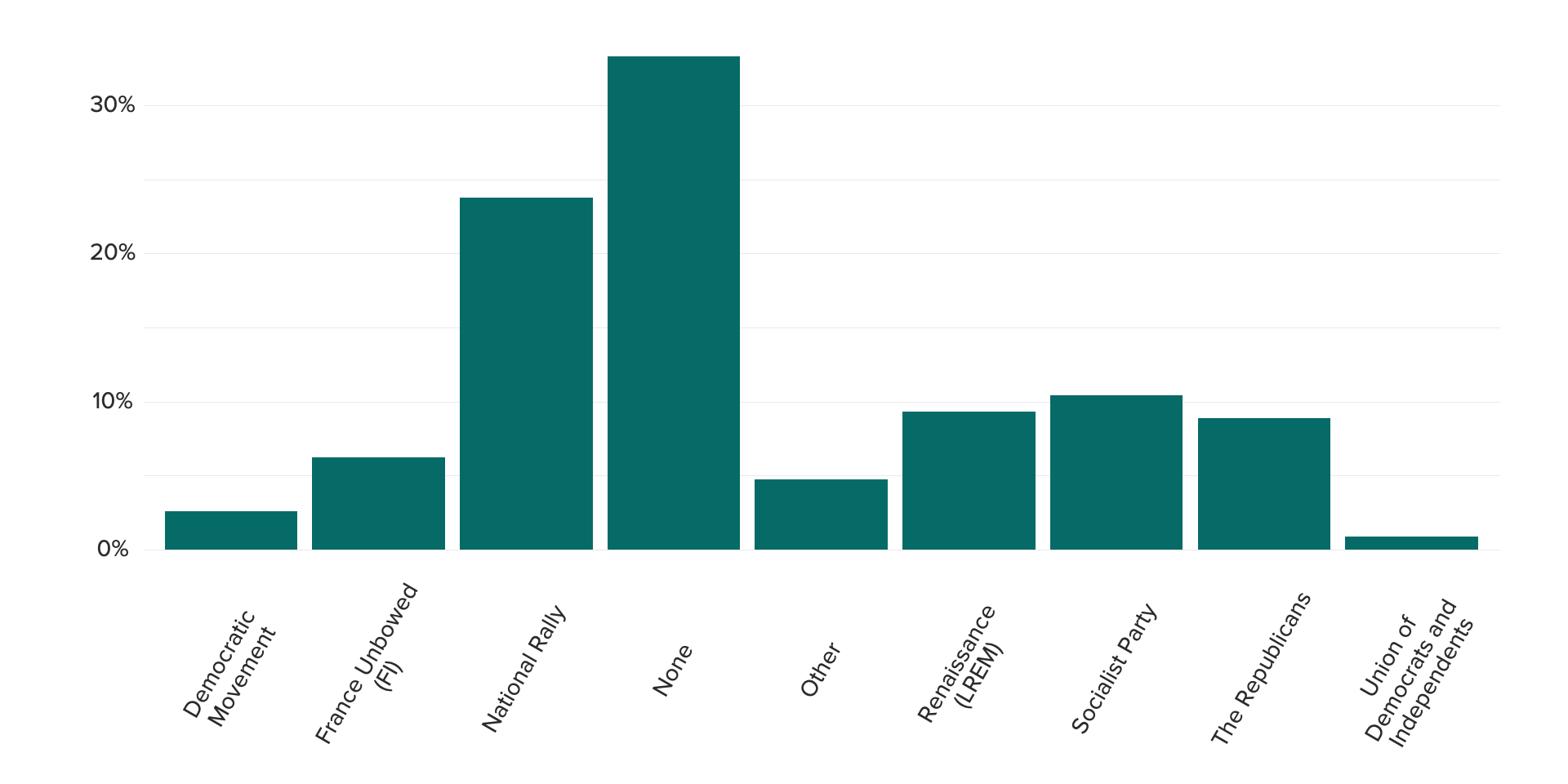

If many countries in Europe are shifting left as well as right, but only a small number of countries have seen sizable increases in extreme views, why are voters nevertheless eschewing traditional centrist parties? It appears that many Europeans — even if they don’t identify as far-right — do not see their views reflected in the parties purporting to represent them. In four out of seven of the European Union countries where we see far-right parties overperforming, when we ask respondents which domestic political party best reflects their own views, the most popular answer is “none.” For a sense of how common this is, twelve countries among the broader set of 39 countries where we ask about political affiliation globally exhibit this pattern.

Far-Right Parties Overperform in Countries Where Pluralities of Adults Say No Party Reflects Their Views

Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in France and Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy garner the most support after the “none” category. In Germany, the mainstream Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and Christian Democratic Union CDU still hold the largest shares of support among those willing to pick a party, but the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) is hot on their heels. And in Romania, over 10% of adults selected the right wing Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR) as closest to their own views, even as the share of Romanians espousing far-right ideology has declined since 2022.

Given these large groups of unclaimed potential voters in several E.U. countries, we will see far-right parties and leaders in those countries — as we have already seen with France’s Marine Le Pen and Italy’s Georgia Meloni — tacking to the center on some issues to try to make themselves more palatable to voters who are not hardliners, but who don’t feel represented by establishment parties. Conversely, we will see mainstream parties trying to co-opt some right-wing narratives they see resonating with disillusioned mainstream voters.

Implications for E.U. parliamentary elections

The most immediate question is how will this rightward move — whether born of political malaise or a true far-right ideological shift — translate into votes in the June 2023 E.U. parliamentary elections? The answer is, incompletely. Many far-right parties in Europe espouse nationalist and anti-E.U. views. So their adherents may be less willing to take the time to vote in elections to an institution they don’t feel connected to; and, if elected, their representatives to the E.U. Parliament may have more trouble cooperating in trans-national party blocs. In countries like France and Germany, where support for far-right parties appears to be more closely associated with political disillusionment with domestic leaders rather than extreme ideological views, many may not be interested enough in the results of the elections to cast their vote.

Nevertheless, projections do show the far-right Identity and Democracy (ID) group and the eurosceptic European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) picking up a number of seats in upcoming elections, though not enough to become the dominant parliamentary group. Still, we expect them to push on the few policy areas where they can garner cross-country agreement — most obviously immigration.

Westphalia lives on

It is important to recall that legislative and deliberative processes in the European Union also make the E.U. Parliament an important but less powerful entity than national bodies in aggregate. So if we want to forecast how trends in Europeans’ political ideology will influence supra-national policymaking beyond June, we would do well to also watch how growing political malaise feeds through from member-state politics to E.U. policymaking after the many elections taking place on the continent over the course of 2024.

Sonnet Frisbie is the deputy head of political intelligence and leads Morning Consult’s geopolitical risk offering for Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Prior to joining Morning Consult, Sonnet spent over a decade at the U.S. State Department specializing in issues at the intersection of economics, commerce and political risk in Iraq, Central Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. She holds an MPP from the University of Chicago.

Follow her on Twitter @sonnetfrisbie. Interested in connecting with Sonnet to discuss her analysis or for a media engagement or speaking opportunity? Email [email protected].