If the Affordable Care Act Falls, People Battling Drug Addiction Will Be Hit Especially Hard, Experts Say

With the fate of the Affordable Care Act in limbo, millions of Americans suffering from addiction would be left in a lurch should the landmark health law be struck down, mental health advocates, addiction specialists and health policy researchers are warning.

The Senate Judiciary Committee will vote on conservative Judge Amy Coney Barrett’s nomination to the Supreme Court on Thursday, with Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) promising a full Senate confirmation vote Monday. With the high court set to hear arguments in a case that could strike down the ACA one week after the Nov. 3 election, her confirmation battle has been centered on health care: Democrats have claimed Barrett’s addition to the court would spell the end of the ACA, while Republicans have sought to downplay the threat.

Yet while the political discourse has focused on the ACA’s popular coverage protections for pre-existing conditions and health insurance in general, the loss of the ACA with nothing to replace it would have far-reaching consequences across the health care ecosystem. And because the ACA made health insurance and addiction treatment more accessible, the elimination of the health care law could be dire for the approximately 20 million Americans with a substance use disorder.

The ACA has withstood other legal challenges, noted Dr. Carrie Fry, an assistant professor of health policy at Vanderbilt University. But while “there's no good time to strike down the ACA for people with substance use disorder, this happens to be a particularly bad time.”

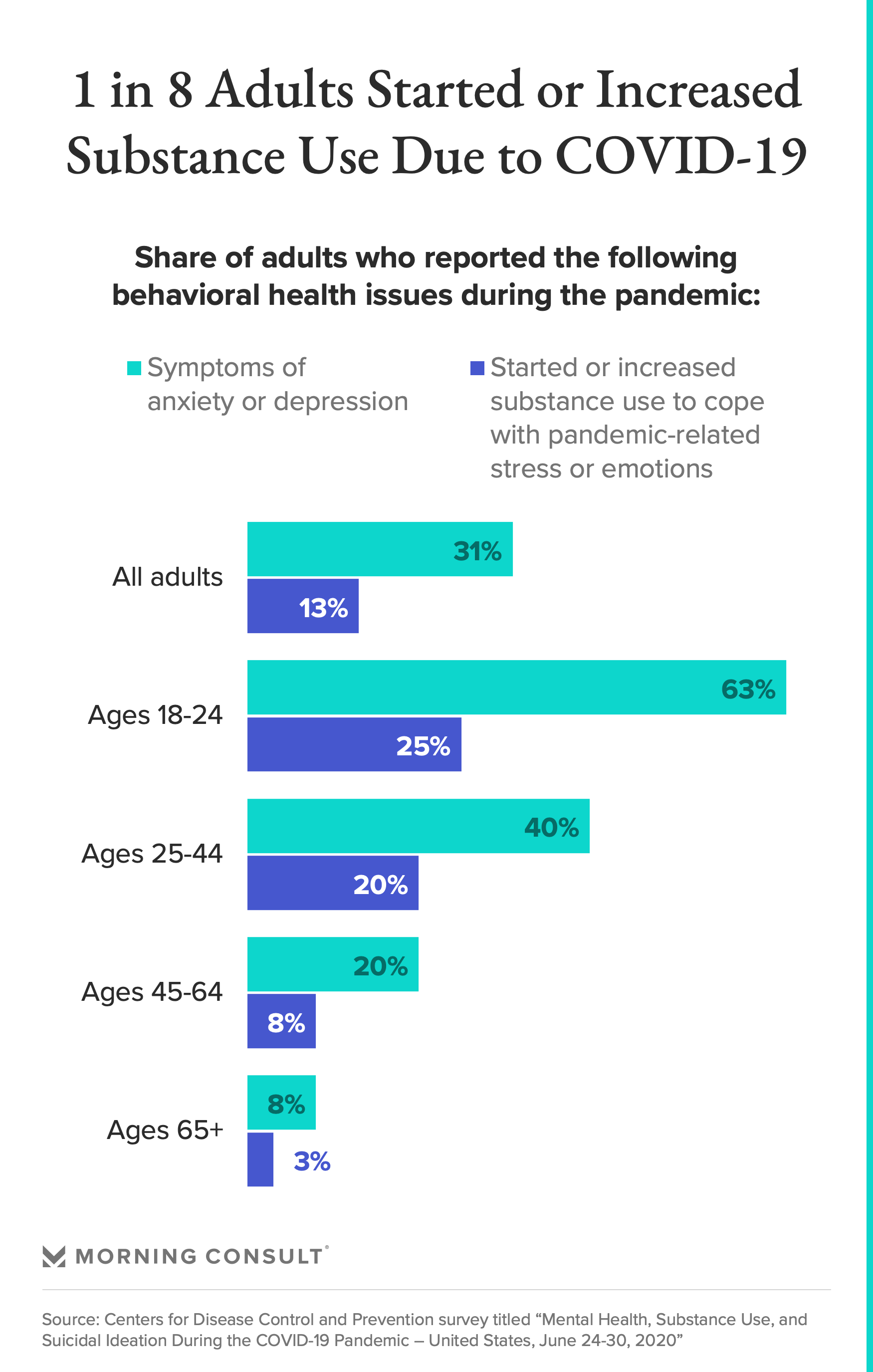

That’s because more than 40 states have reported upticks in opioid-related deaths since the pandemic began, according to the American Medical Association, while 13 percent of adults started or increased their substance use and 31 percent had symptoms of anxiety or depression during the pandemic, a June survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found. The pandemic’s economic strain also means that through June, an additional 3.4 million people had enrolled in Medicaid, the public health insurance program that has played an increasingly large role in paying for opioid addiction treatment since 2010.

“It's throwing gasoline on top of an already out-of-control fire,” said Dr. Benjamin Miller, chief strategy officer of the Well Being Trust, a foundation focused on mental health and well-being.

One of the clearest ways the loss of the ACA would affect people with addiction is through the rollback of Medicaid expansion. The ACA enabled states to expand Medicaid coverage to more low-income adults beginning in 2014, an option 38 states and Washington, D.C., have now taken. Among the nearly 4.1 million people on Medicaid who were treated for substance use disorder in 2017, 38 percent — more than 1.5 million adults — were eligible through expansion, according to a report to Congress published last year. The report excluded some states and others have expanded Medicaid since then, so that number would be higher in 2020.

Medicaid expansion is also associated with improved access to naloxone, the opioid overdose reversal drug, and with lower opioid death rates compared with nonexpansion states.

If Medicaid expansion goes away, “that's massive numbers of people losing coverage and subsequently having to turn to other modalities, which could be buying opioids off the street,” said Dr. Andrey Ostrovsky, managing partner at Social Innovation Ventures and former chief medical officer for the Medicaid program.

The loss of the ACA would affect privately insured people, as well, given it expanded a 2008 parity law that required large employer plans to provide the same level of benefits for mental health and addiction treatment as for other medical care. The ACA went a step further by including treatment for substance use disorders as an essential health benefit and requiring individual, small group and Medicaid expansion plans to cover these services, though enforcement of the parity rules remains spotty.

“Would lots of insurers still cover it? Sure, I hope so,” said Dr. Bradley Stein, director of the RAND Corporation’s Opioid Policies, Tools, and Information Center and an adjunct associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. “But it was put in the ACA for a reason, because it was in insurers' interests to not cover it, or they covered it at such a meager level it was little better than no coverage.”

The law also protects coverage for pre-existing conditions, meaning people cannot be denied insurance if they’ve been treated for opioid addiction in the past, and allows adults to stay on their parents’ insurance plans until age 26. Young adults are both at higher risk for increased substance use and have seen higher unemployment rates during the pandemic, meaning they may not have access to job-based insurance.

If the ACA does fall, “you're taking a population that's disproportionately impacted in terms of substance use disorder treatment, suddenly being uninsured,” Stein said.

Miller said he’s begun having conversations with state Medicaid directors about how they’d address mental health and substance use if the ACA is struck down. But Fry said a state-by-state approach to treatment would result in “a more patchwork system across the country” that would take time to build up and could leave people with few options in the meantime, and states would be doing so with fewer resources from the federal government at a time when their coffers are being squeezed by the pandemic.

Solving the country’s opioid problem has become an increasingly bipartisan issue in recent years, with Congress passing sweeping legislation for addiction treatment, prevention and recovery in 2018 and the Trump administration awarding states nearly $2 billion to fight the opioid crisis in 2019.

But Ostrovsky warned that even if federal or state lawmakers attempt to ensure access to treatment in lieu of the ACA, the loss of Medicaid expansion and the law’s other major provisions could impede the country’s progress fighting social attitudes around addiction, with long-term consequences.

“If all of a sudden you regress to 2009, and we no longer have Medicaid expansion, that, I fear, is going to further stigmatize people with substance use disorder,” Ostrovsky said. “I think that would potentially have a decade or more of ramifications.”

Gaby Galvin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade