Access to Cheap Money Has a Racial Gap

Key Takeaways

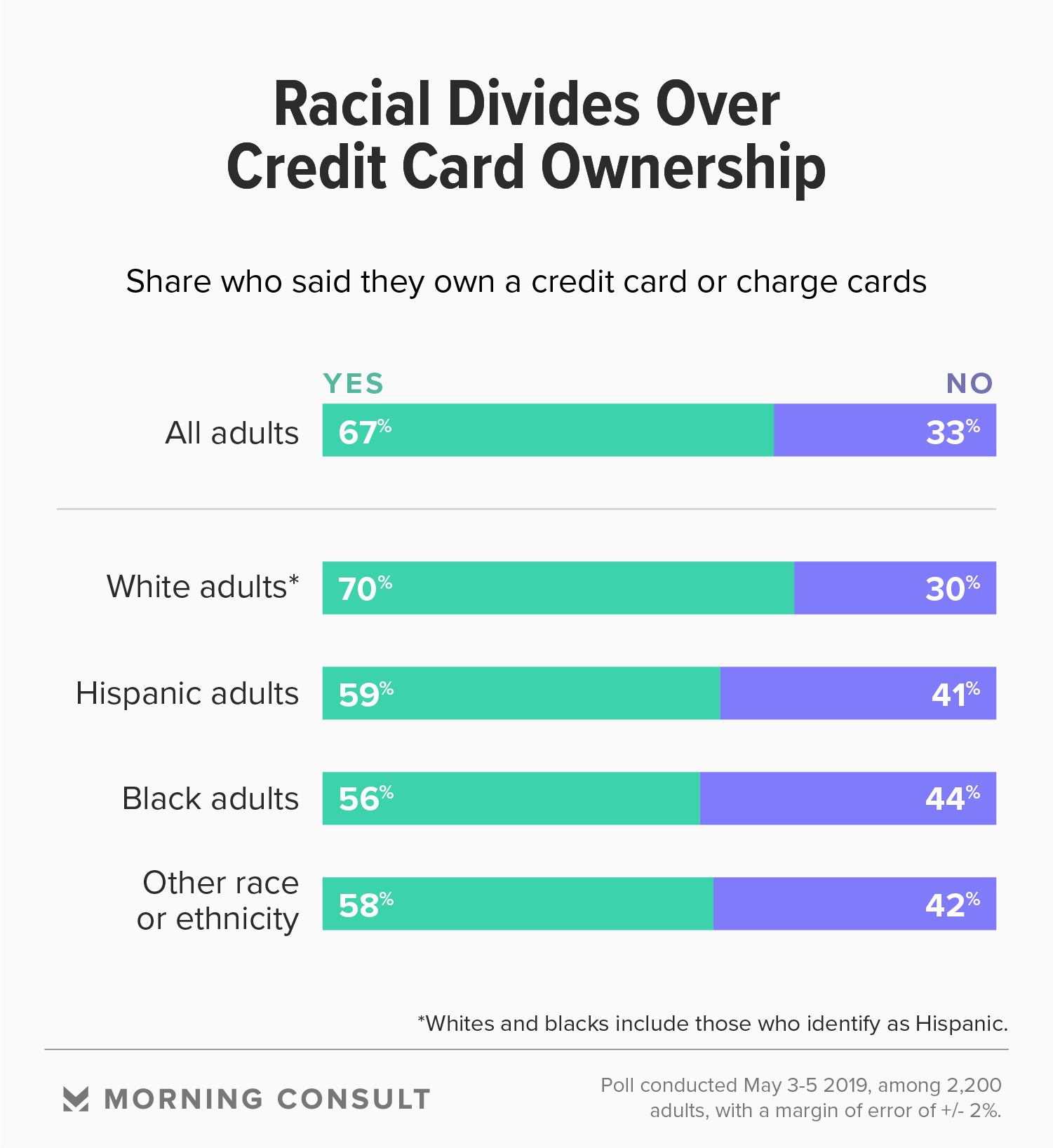

70% of white adults said they own a credit or charge card compared to 56% of black adults.

Credit card owners are 24 percentage points more likely to pay bills on time.

49% of adults without a credit card say they prefer another payment method.

Even in America’s booming consumer credit market, black Americans still have limited access to the most common way to obtain cheap debt: credit cards.

White adults have the highest rate of credit card ownership, according to a recent Morning Consult/CNBC survey. Seventy percent of white adults said they own a credit or charge card, compared to 56 percent of black adults. (White adults include those who identify as both Hispanic and white.)

The Morning Consult/CNBC poll surveyed 2,200 adults from May 3-5 and has a margin of error of 2 percentage points.

For most consumers, cheap debt is critical, and it’s an issue that’s attracted political scrutiny from prominent lawmakers. A good credit score -- built most commonly by consistently paying off a credit card -- can provide lower rates for home loans, offer assistance toward reliable transportation and help with getting a job.

“Basically, credit cards are essential to modern life,” said Andrea Freeman, a law professor at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa who writes about consumer credit. “There are so many things you aren’t able to do without a credit card, like renting a car, buying an airplane ticket, etc.”

And in a country where 40 percent of Americans can’t cover an unexpected $400 expense, access to a credit card can make a huge difference. Credit cards can offer consumers a quicker way out of a financial hole than high-rate options such as payday loans, which can be more than 20 times the cost.

The ability to tap that resource, however, isn’t always straightforward.

“Whatever your first credit is, it really has an impact on the types and cost of credit you have access to going forward,” said Katherine Lucas McKay, a program manager at the Aspen Institute’s Financial Security Program. “Payday loans or other personal loans, that kind of debt puts you on a very different trajectory.”

That makes it even more concerning that black communities face lower access to credit cards, she said.

While there’s plenty of research showing that black Americans fare more poorly than white Americans in consumer credit markets, the question of why is still debated.

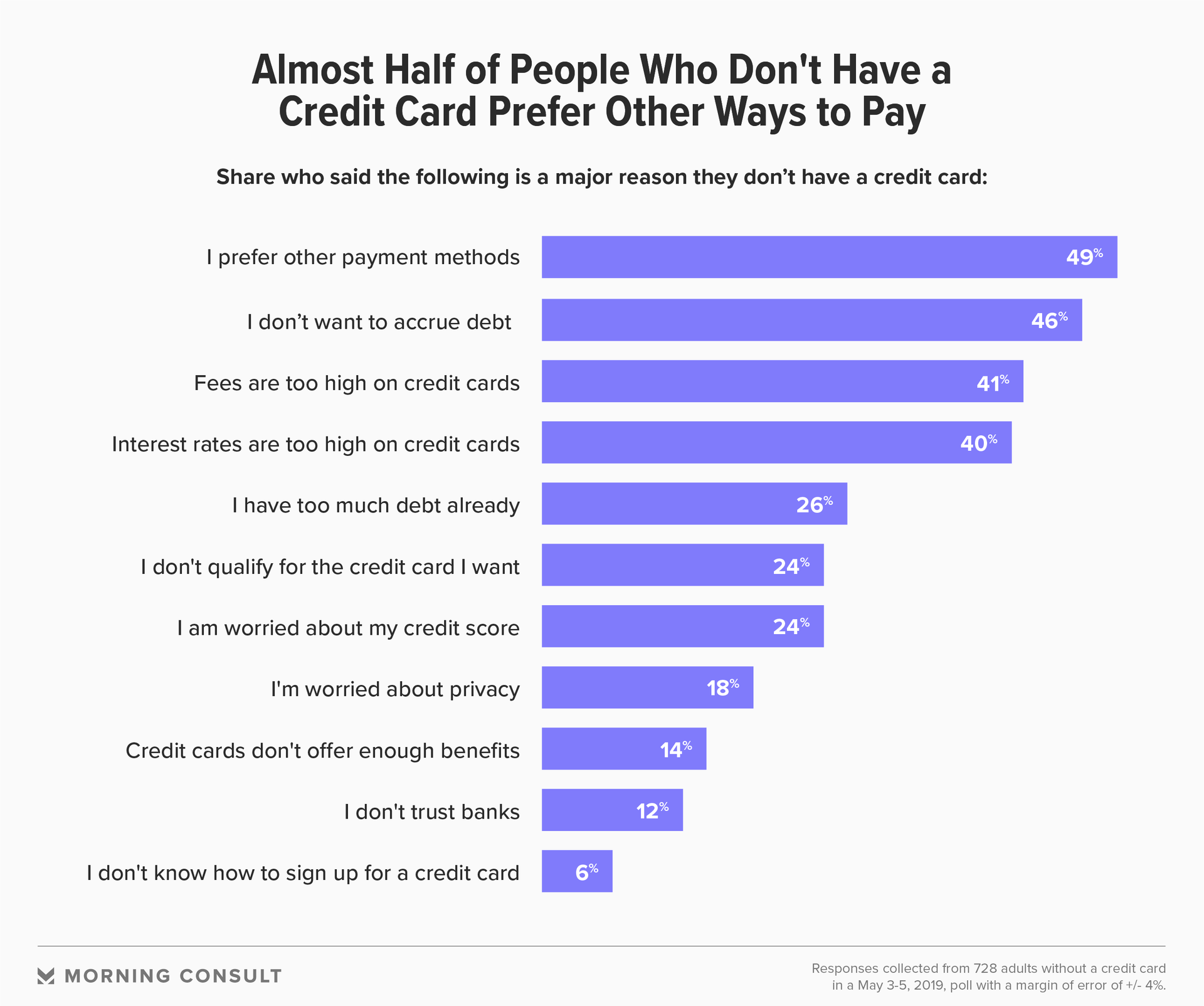

In the recent Morning Consult survey, people who don’t have credit cards were most likely to cite a preference for other payment methods (49 percent) and a desire to avoid debt (46 percent) as the top reasons they don’t have a card. The subsample of non-credit card owners included 728 adults and has a margin of error of 4 percentage points.

Among black Americans, the preference for other payment methods — usually cash or debit cards that don’t involve taking out a line of credit — most likely comes from being disaffected by the consumer credit market, said Catherine Ruetschlin, an economics professor at the University of Utah. At a lower median income than white Americans, black Americans assume lower future financial stability and lower lifetime wealth, which makes them more wary of taking on debt, she said.

Freeman added that economic research suggests redlining still exists among credit card companies, although the companies have disputed it in the past.

“What the research reflects is the fact that bad credit card terms usually go to people of color, so when they get into a contract with the credit card company, they are getting a bad deal,” she said. “So it makes more sense to use another payment method.”

There’s a misconception that all credit card use is irresponsible, and that unlike other kinds of debt such as a mortgage, it won’t contribute to wealth accumulation over time, Ruetschlin said.

“Credit cards can be an investment in getting to your job every day, seeking promotions and better opportunities,” she said. “There’s disagreement in the assessment of how credit card use fits into people’s lives, that people are using it as flagrant consumerism, which really isn’t the case when you look at people who are turning to credit cards overall.”

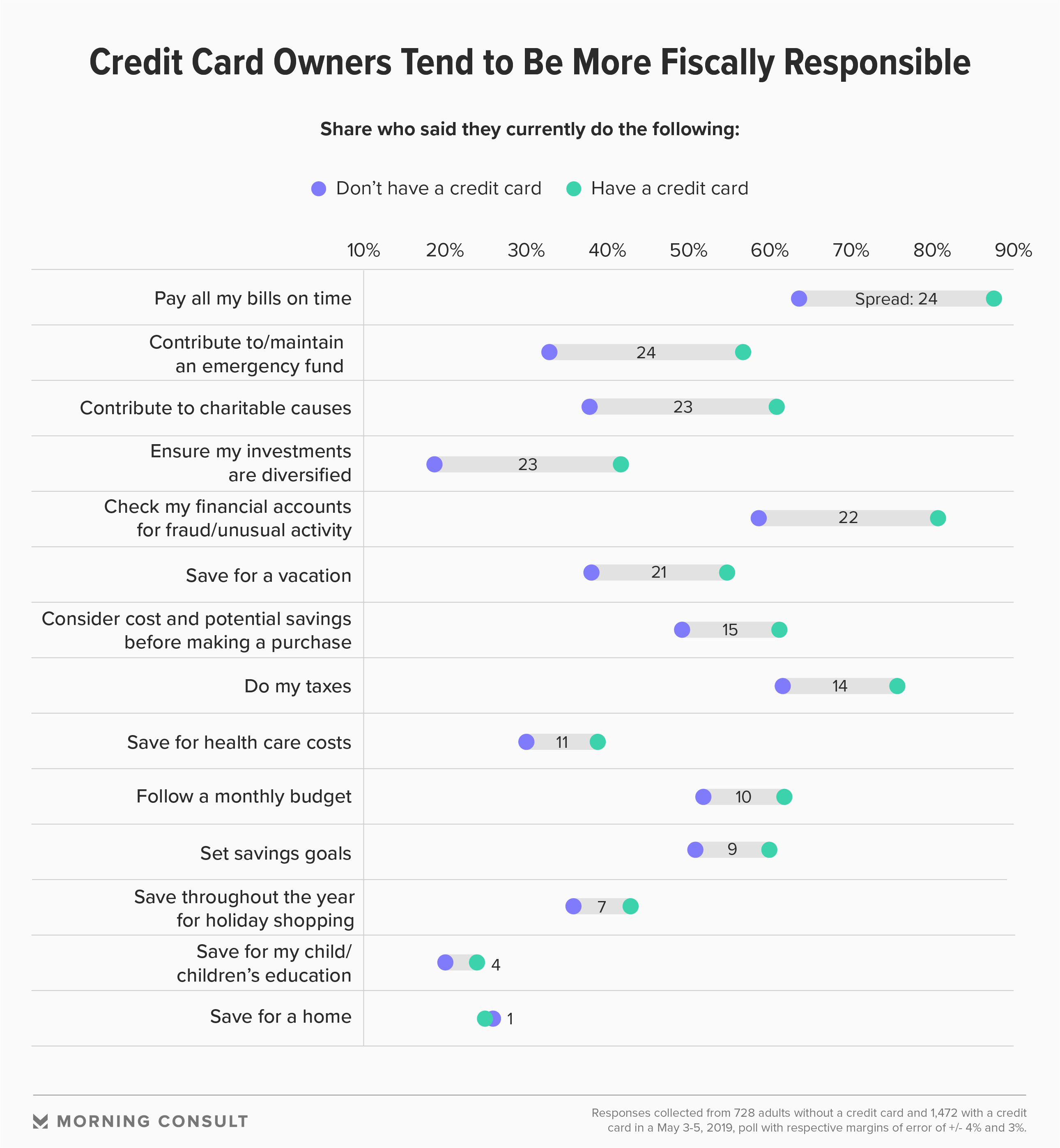

In fact, credit cards could encourage the kinds of financial behaviors that personal finance experts recommend, according to the Morning Consult survey.

Credit card owners are 24 percentage points more likely to pay bills on time and to contribute to an emergency fund than those who don’t have a credit card. They’re also 23 percentage points more likely to have a diverse investment portfolio and 22 percentage points more likely to check their financial accounts for fraud or unusual activity.

This ability to build wealth makes credit cards and the regulation surrounding the consumer credit market subject to political scrutiny leading up to the 2020 presidential election.

The industry is already a favorite target of some prominent left-leaning politicians. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), a Democratic presidential nominee hopeful, and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) introduced a bill that would cap credit card interest rates at 15 percent.

The proposal, which is likely to stall in the GOP-controlled Senate but is a significant messaging move, has mixed reviews from economists and consumer advocates.

“Anything that helps credit card consumers, in general, is going to help consumers of credit more,” Freeman said. “They have less access, they have worse terms, so anything that’s out there that draws attention to the nature of the industry is a good thing.”

Aaron Klein, a Brookings Institution fellow in economic studies, and Lisa Servon, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, argued in a Washington Post editorial that the Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez proposal would actually “hurt the people it’s designed to help” by cutting off credit access to those who have struggled to get it in the first place.

Ruetschlin had a similar criticism: “Opening up low-cost access to credit for individuals who may have been denied access to credit and need it would be a better place to start.”

Claire Williams previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering finances.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade