Amid COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout, a Quarter of Health Care Workers Say They Won’t Get a Shot

Key Takeaways

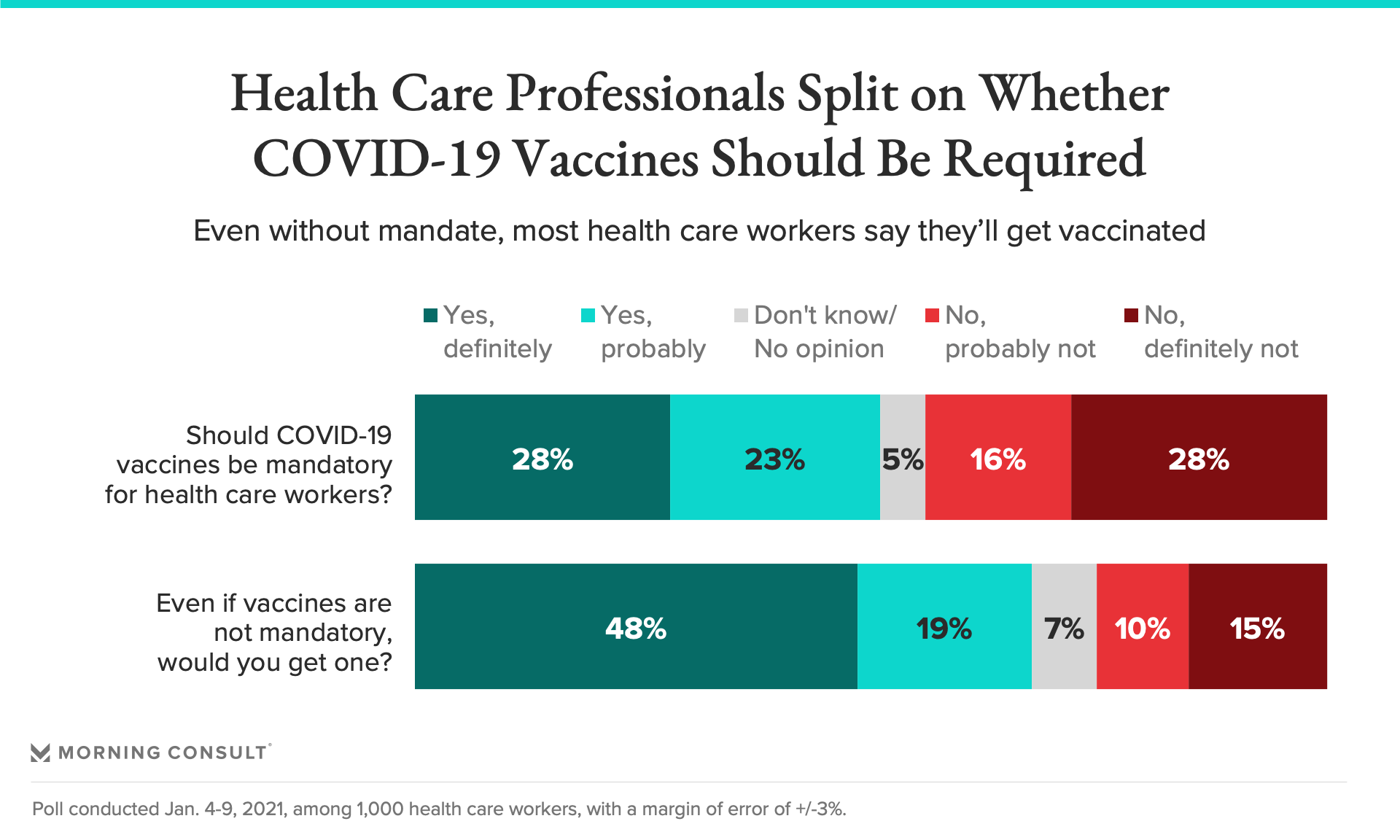

51% of health care workers said people in their field should be required to get vaccinated, while 44% said vaccines should not be mandatory.

Two-thirds of health care workers said they would get vaccinated even if it weren’t required.

38% of health care professionals who haven’t yet gotten a vaccine said they were nervous about its unknown long-term effects.

A new special report from Morning Consult explores how health care workers have fared during the pandemic and how they view the broader COVID-19 response. The data is drawn from a poll of 1,000 health care workers.

When COVID-19 first struck the United States, health officials warned that developing an effective vaccine in record time would be a complex — and perhaps impossible — feat. As the months wore on and efforts turned to the equally pressing task of swaying a wary public to get vaccinated, the health sector wasn’t necessarily contending with how to build trust among its own rank and file.

But many medical workers, despite their proximity to the crisis, have indeed balked at the idea of getting their shots. A new Morning Consult survey of 1,000 health care workers indicates vaccine hesitancy among the group is widespread, with a quarter saying they would refuse a shot altogether.

“Vaccine hesitancy overall goes back; it's not something that's brand new,” said Dr. Seth Trueger, an emergency room doctor and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. Trueger said he was concerned early on that COVID-19 vaccines might be rushed, but felt reassured when drugmakers took “good faith” steps to show they were meeting federal regulators’ high standards for authorization. He got his second shot Jan. 8.

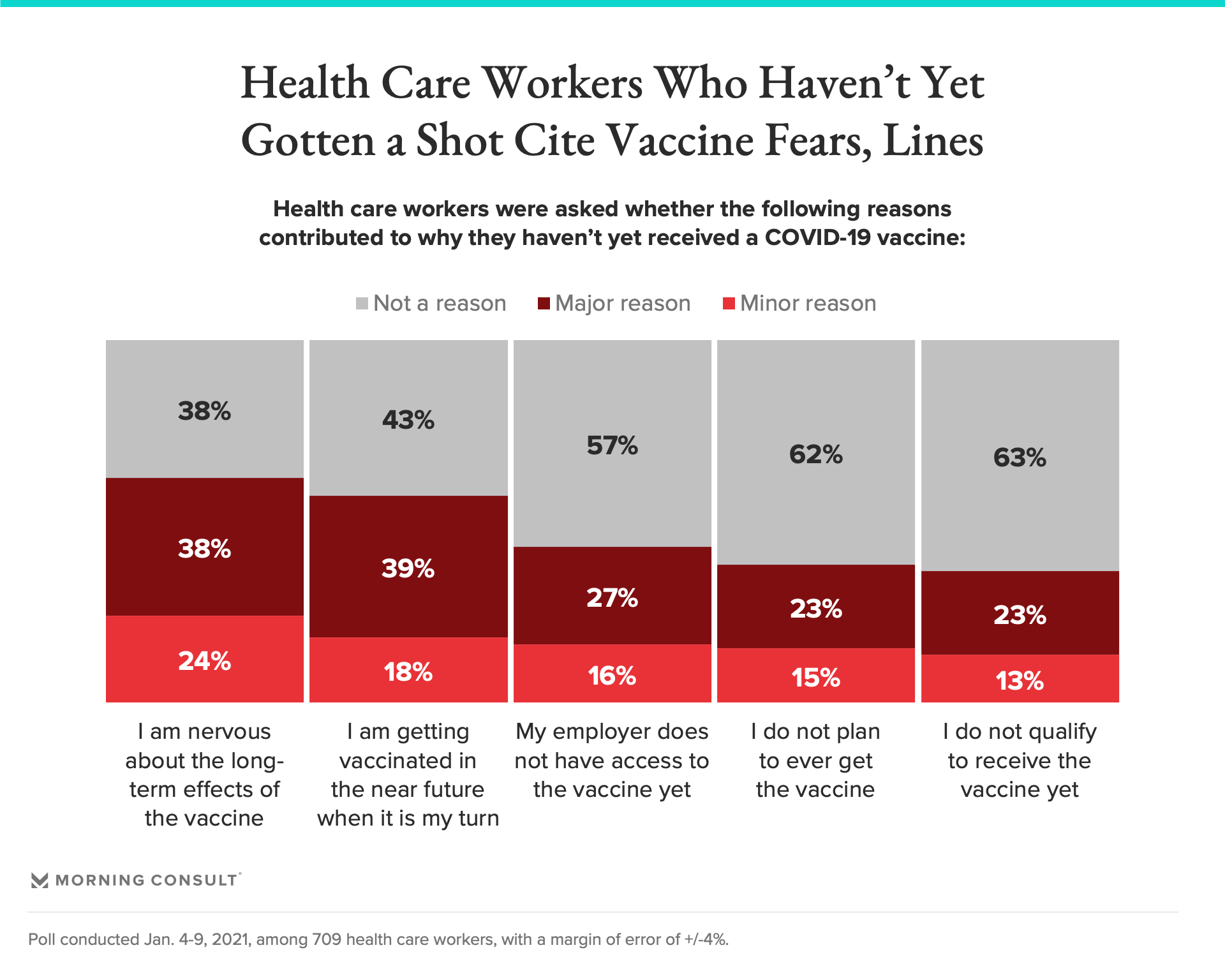

As of Jan. 4-9, when the survey was conducted, 29 percent of respondents had gotten at least their first COVID-19 shot. The remaining 709 respondents were asked about the major reasons they hadn’t yet been vaccinated: 38 percent said they were nervous about the long-term effects of the vaccine, and 23 percent said they don’t plan to ever get vaccinated. In the open-ended portion of the survey, commonly cited reasons included having allergies, being pregnant and wariness of going first.

“While I am generally all for vaccines I am a little hesitant to be one of the first people to receive it,” one health care worker wrote. Another said they “don’t understand or know what the long-term affects [sic] of this vaccine will be.”

Vaccine hesitancy among medical staff has been an issue across the country. In New York City, for example, roughly 30 percent of employees in the public hospital system had turned down a vaccine earlier this month, city officials said. In Ohio, as many as 60 percent of nursing home employees wouldn’t take a shot at the end of December.

Other health care workers said they haven’t been vaccinated yet due to the logistics of the rollout: 27 percent said their employer didn’t yet have access to doses, while 23 percent said they weren’t eligible for a shot and 39 percent said they had plans to get vaccinated soon when it’s their turn. Survey respondents included nurses, physicians, home health aides, people in administrative roles and others; about 2 in 5 had cared for COVID-19 patients directly.

The lack of availability may in part reflect the rollout’s focus on hospitals, which has left many primary care providers and other medical workers without a direct way to get a shot. For example, one health care worker surveyed who said they work directly with patients in a small office that is not affiliated with a health system had “no idea” how to get in line for a vaccine.

And while nurses and doctors became the joyful online faces of the early vaccine rollout, getting a shot has also led to some conflicting emotions for providers who work with high-risk patients who aren’t yet able to get vaccinated.

“In a way, we still feel a little bit guilty that we're getting it and our patients aren't,” said Dr. Randall Oyer, an oncologist and medical director of the Cancer Institute at Penn Medicine Lancaster General in Pennsylvania and president of the Association of Community Cancer Centers.

Beyond their own prospects, the poll indicates 55 percent of health care workers are not confident that the country’s vaccine rollout will go smoothly, while 39 percent are confident in the process.

The vaccine divide has put some medical workers in an awkward position: prodding coworkers who have so far opted out. In Massachusetts, Kelly Hennessy, a nurse practitioner who runs the East Boston Neighborhood Health Center’s COVID-19 testing department, has spoken with younger women concerned about the vaccine’s potential effects on fertility, a theory that has circulated on social media but is not supported by scientific evidence.

“Just saying: 'We have to trust the science. Your fears are real, but we can show you all the research behind it,’” Hennessy said of her conversations with coworkers who aren’t sure about getting vaccinated. “But I truly think that the best way is to lead by example.”

She’s scheduled to get her second shot Monday.

Health systems and other employers have taken different tacks to compel health care workers to get vaccinated. Houston Methodist, an eight-hospital system that employs some 26,000 people, is offering $500 bonuses to workers who get their shots, while Atria Senior Living, a major chain of senior living facilities, will require its more than 10,000 employees to get vaccinated by May.

Health care workers were split on whether vaccines should be mandatory for those in their profession, with 51 percent saying they should definitely or probably be required to get a shot and 44 percent saying they should not. Two in three said they would get vaccinated even without a requirement to do so, while 25 percent said they wouldn’t and 7 percent said they didn’t know or had no opinion.

“I think the important thing is that it's voluntary,” Hennessy said, because mandating that people get vaccinated might spook them or cement their point of view against the shots. “You can't speak down to anyone about it, because you're not going to change their mind.”

Gaby Galvin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade