Apple Tops the List of Tech Stock Holdings by Key Regulatory Figures in Congress

Key Takeaways

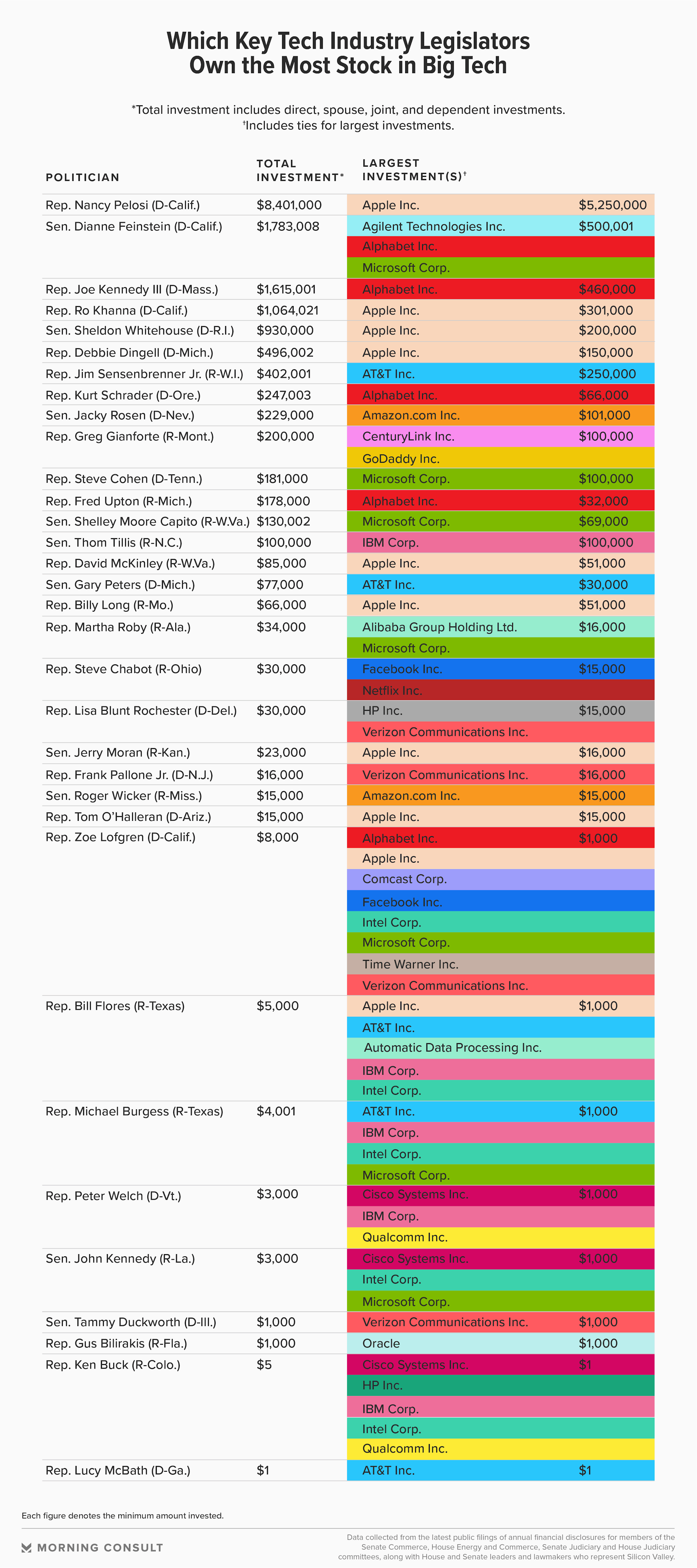

Out of the 145 key legislators tasked with regulating tech, 33 disclosed shares in tech companies either on their own, through a spouse or a dependent child.

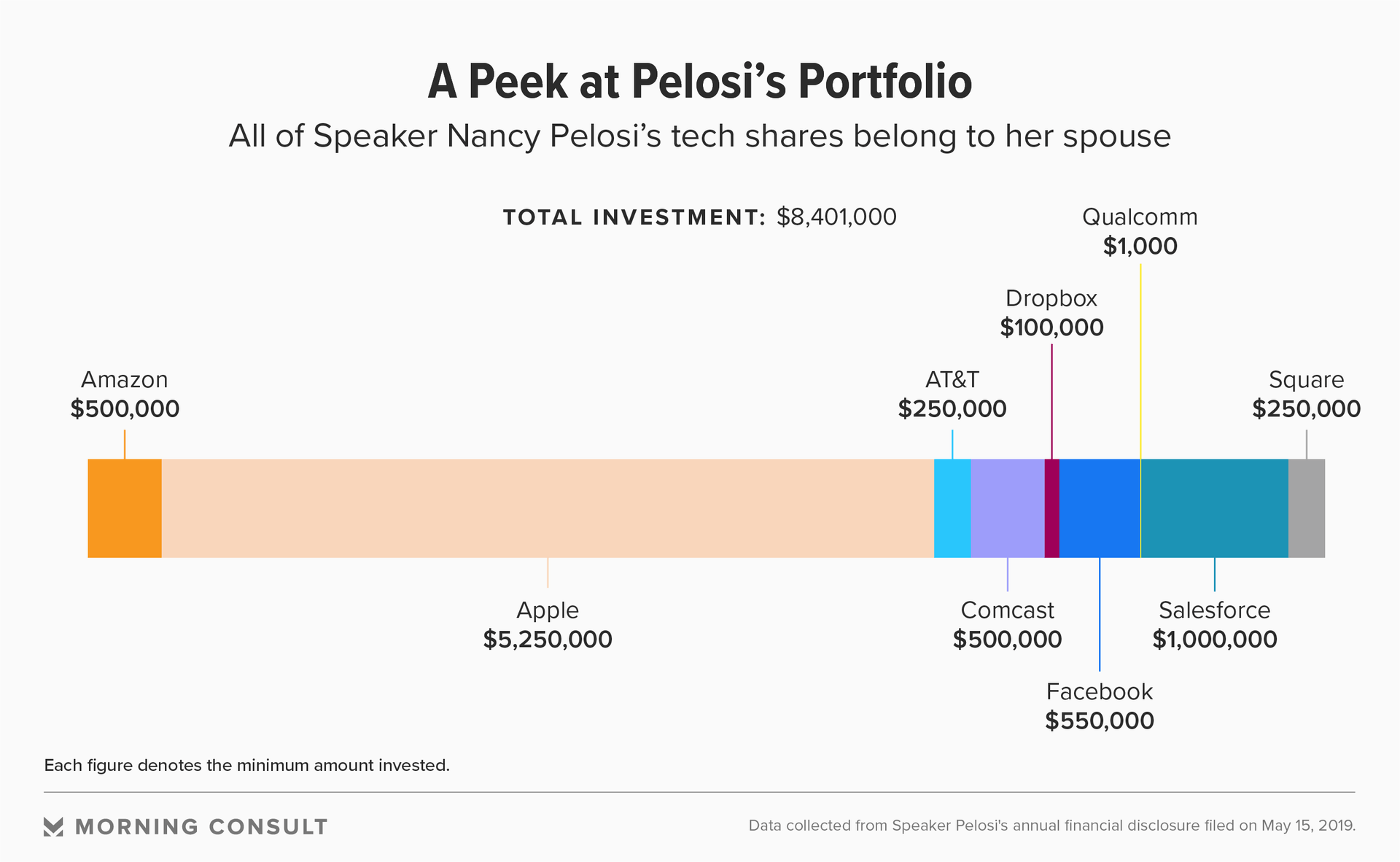

Pelosi’s shares in tech companies had a total value of at least $8.4 million.

In June, the House Judiciary Committee’s antitrust subcommittee began what it called Congress’ first examination of the competition in the tech industry. David Cicilline (D-R.I.), the subcommittee’s chairman, said “four decades of weak antitrust enforcement and judicial hostility to antitrust cases” were reason enough to investigate the industry, echoing concerns from his Democratic colleagues.

Yet many key congressional members in both parties involved with the investigation and similar legislative discussions, including those looking at data collection and privacy practices, may have more than just their legislative records at stake if these efforts bear fruit.

Of the 145 lawmakers who sit in positions that have the power to sway negotiations on tech legislation, 33 hold tech shares through personal holdings, a spouse or a dependent child. Annual financial disclosures included in Morning Consult’s analysis were filed this year or in 2018 and represent the member’s finances from the year prior, and all figures come from the latest filings as of July 2. (The full data set can be downloaded here.)

The member of Congress with the greatest amount of money in technology stocks was Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.), who had at least $8.4 million in such investments through her husband, Paul Pelosi, the founder and owner of real estate and venture capital firm Financial Leasing Services. Speaker Pelosi’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

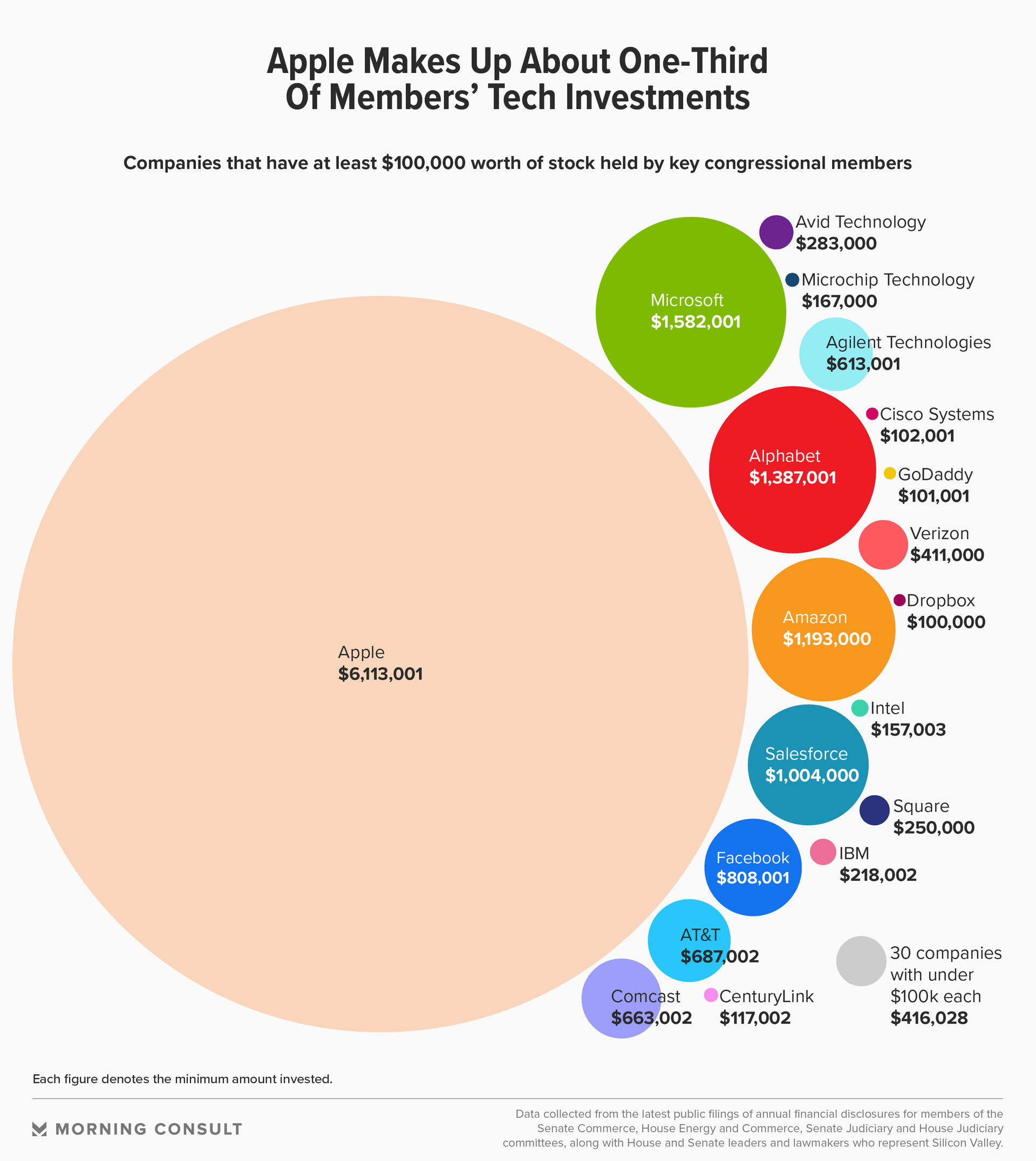

And Pelosi’s $5.25 million in Apple Inc. stock was the reason that Apple represented the largest share of tech investments among lawmakers, with $6.1 million. The companies also popular among lawmakers were Microsoft Corp., Alphabet Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., with investments totaling at least $1.6 million, $1.4 million and $1.2 million each.

On the House Judiciary’s antitrust subcommittee, two of the panel’s 13 members have disclosed owning shares in the tech and telecommunications industries, including ranking member Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.). In his 2017 financial disclosure, the most recent available, Sensenbrenner disclosed that he owns at least $400,000 worth of stock holdings, mostly in telecommunications companies such as AT&T Inc. and Verizon Communications Inc.

A spokesperson from his office said the congressman holds a “diverse portfolio of investments which carry no weight in his decision-making as an elected official” and said Sensenbrenner discloses more than is required of members of Congress in his filings each year.

Senate Commerce Chairman Roger Wicker (R-Miss.), whose panel is crafting a federal data privacy bill, reported owning between $15,000 and $50,000 worth of Amazon.com Inc. shares in his 2018 financial disclosure, while Sen. Jerry Moran (R-Kan.), who sits on the committee’s six-member data privacy working group, reported at least $23,000 worth of shares across five major tech companies -- Alphabet Inc., Apple Inc., Microsoft Corp., Sprint Corp. and Verizon Communications Inc. -- being owned by himself, his spouse and jointly together.

Wicker’s office declined to comment. A spokesperson in Moran’s office said in a statement that the senator’s investments are made independently by a financial adviser who has full discretion over the accounts.

Owning technology stock doesn’t necessarily mean a lawmaker is more likely to be against or for regulation. Both finance and government ethics experts say that many factors play into how investments of this nature can impact a legislator’s voting record: who exactly owns the stock, the size and timing of the investment and how relevant the investment is to the lawmaker’s congressional work.

It’s also unclear whether how more stringent regulation would move technology stocks. James Angel, an associate professor at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business who specializes in financial market regulation, said the share price for a major tech firm could jump if a regulator announced it was breaking the company up – meaning legislators could profit from updated antitrust rules.

“If everybody thinks it’s going to be the worst possible breakup, and it’s less than catastrophic, the stock price can go up on the announcement of some regulatory event,” he said.

But Craig Holman, government affairs lobbyist for the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen, which was successful in pushing for the passage of S. 2038 in 2012 to expand financial disclosures in Congress, stock holdings by legislators can color the “entire legislative process” by providing the incentive to take action in a way that could benefit the stockholder.

“Even if the member happens to be so virtuous that he or she isn’t really voting for their bottom line, it certainly looks that way,” he said.

Among the legislators who disclosed owning stock in tech companies, several spokespersons told Morning Consult that the members relied on a third party to manage their holdings – which can indicate that the legislator has little to no control over where their stock investments land.

For example, seven of the legislators who own tech stocks – Reps. Lisa Blunt Rochester (D-Del.), Greg Gianforte (R-Mt.), Joe Kennedy III (D-Mass.), Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), Frank Pallone Jr. (D-N.J.), Martha Roby (R-Ala.) and Fred Upton (R-Mich.) – have holdings that sit in a trust, which could be managed by a third party in an effort to remove a layer of accountability between the member and their investments. Others might rely on a run-of-the-mill portfolio manager to organize their investments.

One way to avoid the appearance of a conflict of interest while still being able to participate in the public markets is to set up a qualified blind trust, an arrangement where a trustee makes financial decisions for a fund that are not disclosed to the owner. Another option is to focus on investing into mutual funds, which funnel investor money into a diversified mix of securities, such as stocks, bonds and short-term debt.

While acknowledging that a qualified blind trust would indeed prevent stock holdings from influencing the owner to act in a certain way, Holman said the problem is that external management of investment accounts alone does not remove the risk of a conflict of interest.

“By saying ‘third party,’ that’s just loose language for saying they have a person who manages their stocks, which just about anybody who manages stocks has,” he said.

Donald Sherman, deputy director at the advocacy group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, said that although lawmakers' stock investments can be a potential conflict of interest, they are a small drop in the bucket when it comes to other factors that could corrupt the lawmaking process, such as lobbying and campaign finance.

Sherman, who was chief oversight counsel on the House Oversight and Reform Committee from 2014 to 2015, said he would have more concerns about those who take campaign contributions from companies or those who land jobs as lobbyists working for the industries they used to regulate after their government careers.

“You look at a member who owns maybe $65,000 worth of stock in Google or Facebook and that is certainly a lot of money to me -- and it’s a lot of money to the average American -- but the question you have to ask yourself is if this is enough money for someone to put their political career at risk,” Sherman said. “That seems like it’s not super plausible, but also it has to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.”

Sherman also said the working perspective of Congress on stock investments is typically that everything is ethical so long as it’s disclosed in the publicly available financial disclosures database.

And Angel said that’s the main reason Congress’ financial disclosures are here: for constituents to come to their own conclusions.

“The problem is that we keep electing humans to the legislature and every single human has their biases, their flaws and their baggage,” Angel said. “That’s why we rely on these systems of disclosure.”

Joanna Piacenza contributed to this report.

Clarification: This story was updated to clarify Donald Sherman's role on the House Oversight and Reform Committee.

Sam Sabin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering tech.