Arkansas’ Move to Dip Into Abandoned Investments Stokes Fears of Wider Trend

Arkansas has shortened the wait before it can claim abandoned retirement accounts and other assets, a move that some mutual fund industry and consumer advocate groups worry could prompt other states to follow suit and potentially upend consumers’ retirement plans.

Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson (R) on March 15 signed into law a measure eliminating a three-year waiting period before the state can liquidate bonds, mutual fund accounts or bank deposits that have been dormant for seven years. Other states typically need to try to find the owner of the assets for a set period, ranging from several months to several years, before claiming the funds.

The Arkansas law, which passed with broad support from the state Legislature, could mobilize similar efforts elsewhere in the country, especially if the measure faces no legal challenges or public outcry, according to the Investment Company Institute, a trade group for the mutual funds industry.

“We’re concerned it’s the start of a national trend,” said Tami Salmon, assistant general counsel at the Investment Company Institute.

There is a reputational risk to mutual fund companies when states take assets from customers, Salmon said: If a customer finds that a company couldn’t locate them and he or she lost out on potential earnings, that might affect investing decisions with that company in the future.

Often, this is how assets get claimed by state governments: A person gets a new job, rolls their 401(k) into an IRA or other investment account and moves. If the financial company can’t get ahold of that person at their new address, or if that person doesn’t contact their financial institution for a set period of time, the account might be deemed abandoned, even if the person is still making automatic payments.

After a set period of time, that account is turned over to the state. Owners can reclaim the asset at any time.

But what the owners lose is the chance to see those assets grow, and the lost gains can be substantial.

For example, if a Roth IRA worth $24,728 (which Vanguard Group says was the average balance in defined contribution plans in 2017 for people ages 25-34), is liquidated, it could miss out on about 34 percent growth over a 10-year period, or about $8,500. That’s assuming no annual contribution and a 3 percent annual rate of return, which barely beats inflation, according to Bankrate’s calculator.

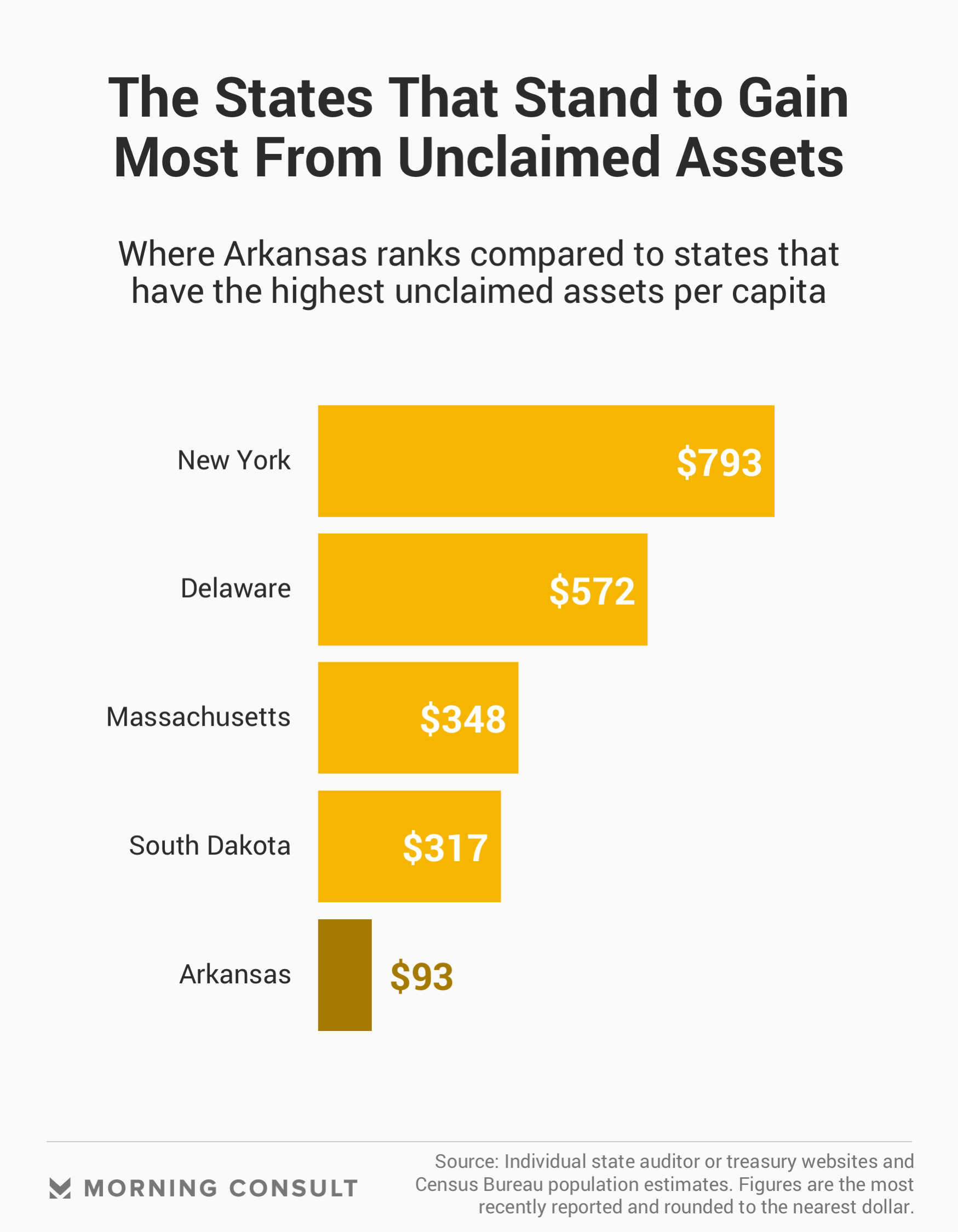

The amount of unclaimed assets in Arkansas -- about $280 million -- is relatively small compared to states such as New York and Delaware, where many financial companies are headquartered. Still, any move to shorten the waiting period before a state can take an asset could pose a huge problem for consumers, especially if the idea gains steam among states.

In larger states, a law eliminating the waiting period could have a far greater impact and affect larger sums of money.

California alone, for example, holds $9.3 billion in escheated assets, or assets turned over to the state. Nationwide, the National Association of Unclaimed Property Administrators estimates there are more than $40 billion in such assets.

For years, cash-strapped states have become more aggressive about taking these unclaimed assets and using them as a source of revenue, according to the Investment Company Institute.

The most prominent of these states is Delaware, Salmon said. With no sales tax, unclaimed assets are the third-largest source of revenue for the state, according to the state’s yearly budget breakdown.

There’s a higher-than-average level of unclaimed assets in Delaware, as in other financial hubs, because in some circumstances, abandoned property might be turned over to the state where the company that manages that account is incorporated or headquartered.

“It’s a way that states can try to generate revenue without taxes, but it can be pretty unsavory,” said Aaron Klein, policy director of the Center on Regulation and Markets at the Brookings Institution. Klein worked on unclaimed asset policy in his previous role at the Treasury Department as deputy assistant secretary for economic policy.

Delaware faces numerous lawsuits related to its unclaimed assets law -- which in most cases, says that dormant accounts are turned over to the state after a period of five years. Delaware can liquidate investments immediately once they’re turned over to the state, but must provide notice to the owner before liquidation and compensate the owner at full market value if the claim is made within 18 months of the liquidation notice.

California requires businesses to turn over unclaimed property in a far shorter period of time -- three years in most cases -- than the Arkansas law. California can liquidate securities no sooner than 18 months after they’ve been taken by the state.

In Arkansas, Deputy Auditor Skot Covert defended the new law by pointing to the state’s seven-year “dormancy period,” or the amount of time the financial institution has to find the owner of the unclaimed asset before turning it over to the state, which is longer than is typical. Most states have a dormancy period of three to five years.

“At year seven, when these assets are just being escheated to Arkansas, most other states have been in possession for three years and already liquidated the asset,” he said.

States often contend that they are in a better position to safeguard unclaimed assets and that they have better resources than financial companies to locate the owners of accounts.

Covert said the state’s new law helps Arkansas “preserve whatever value is left is in the best interest of the consumer.”

Still, it isn’t likely that the owner of an abandoned investment account will come looking for it. Salmon estimates that 78 percent of assets deemed abandoned will remain unclaimed. States rely on this statistic when they liquidate accounts and designate more than a third to their budgets, Salmon said.

“They bank on the fact that they’re never going to have to pay out most of the money,” Salmon said.

Claire Williams previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering finances.