Voters Largely Believe Biden Wants Bipartisanship, but They Don’t Agree With White House’s New Definition of the Term

Key Takeaways

43% of voters say something needs to have cross-party support from both voters and lawmakers in order to be considered bipartisan.

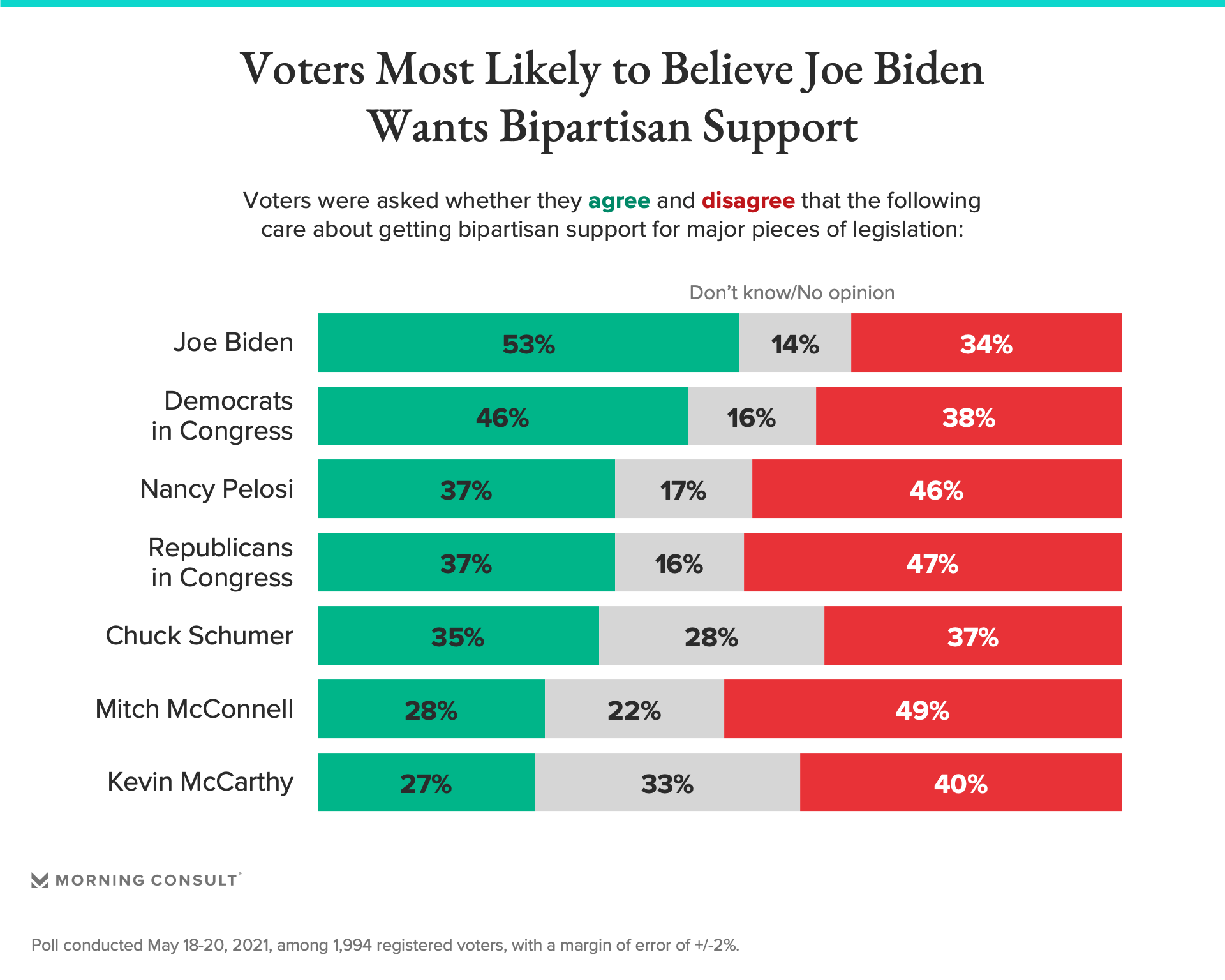

53% say Biden cares about getting bipartisan support for major pieces of legislation, more than any other leader in Washington.

59% of Republicans say no action in Congress is better than action led by one party, compared with 37% of Democrats.

The White House introduced a new definition for what the concept of bipartisanship means in Washington during the first few months of Joe Biden’s presidency.

“If you looked up ‘bipartisan’ in the dictionary, I think it would say support from Republicans and Democrats. It doesn’t say the Republicans have to be in Congress,” Biden adviser Anita Dunn told The Washington Post in April, after the administration’s COVID-19 relief legislation faced unified opposition from GOP lawmakers despite widespread support from Democratic and Republican voters.

As the administration has moved on to Biden’s massive infrastructure and social spending packages and looks to advance bipartisan measures on policing and immigration legislation -- in addition to forming a commission to investigate the Jan. 6 Capitol attack -- a new Morning Consult poll shows that the White House’s operating definition isn’t going to cut it for voters, though they do believe Biden is genuine in his attempts to reach across the aisle.

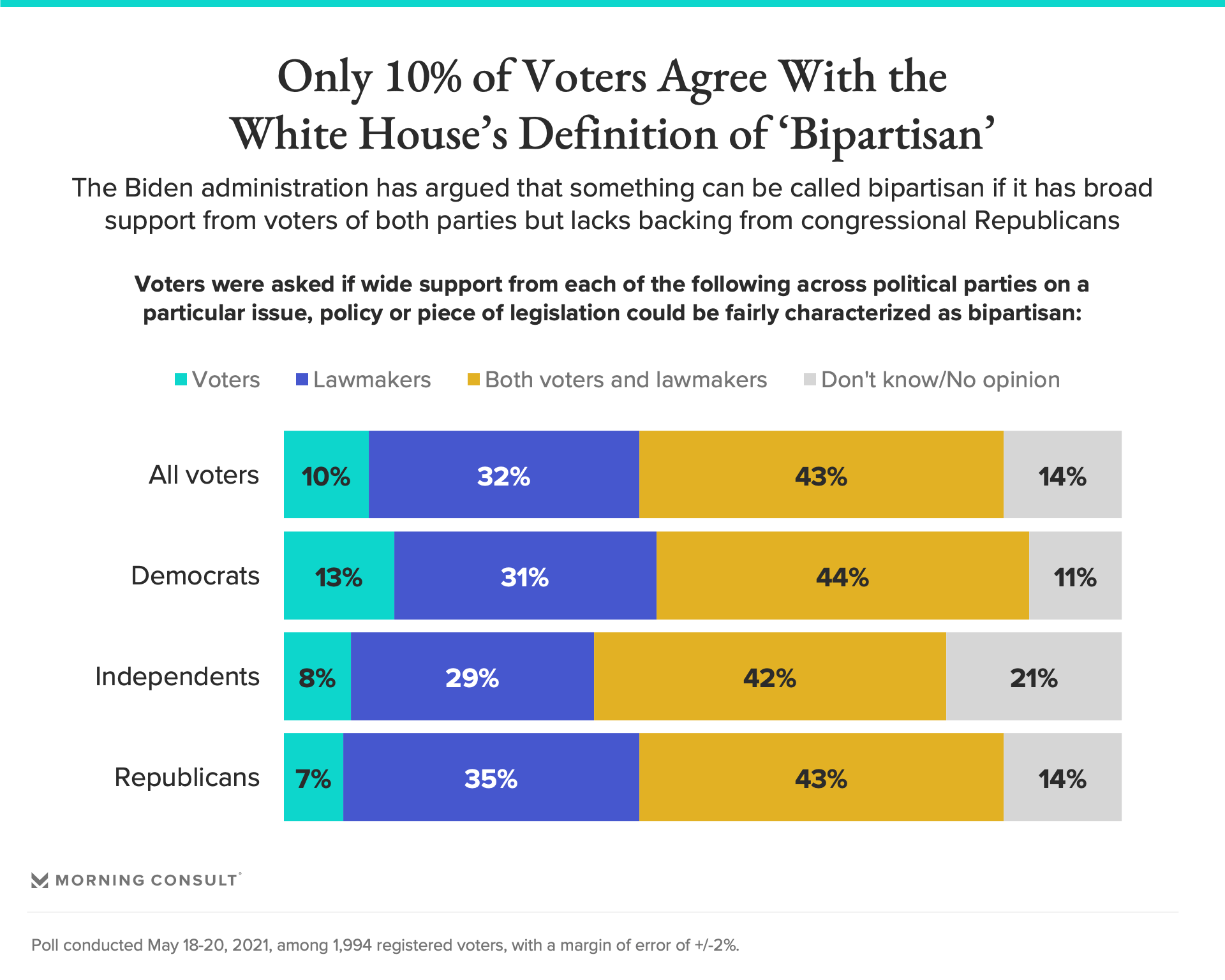

When given the choice, just 1 in 10 voters agree that something counts as bipartisan when it’s supported by Democratic and Republican voters, while a third (32 percent) say something is bipartisan when it is backed by lawmakers of both parties. The largest share (43 percent) said something needs to have cross-party support from both voters and lawmakers in order to be considered bipartisan.

The White House did not comment.

The survey found little disagreement between voters of the two parties on what counts as bipartisanship, suggesting that the White House’s messaging on the issue isn’t resonating with its base as the window for multi-party agreement to advance his infrastructure agenda in Congress appears to be closing.

“Most everyone in the caucus, with the exception of one or two, understand that you gotta fish or cut bait,” said Jim Manley, a former top aide to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) during the presidency of George W. Bush and the early years of Barack Obama’s tenure.

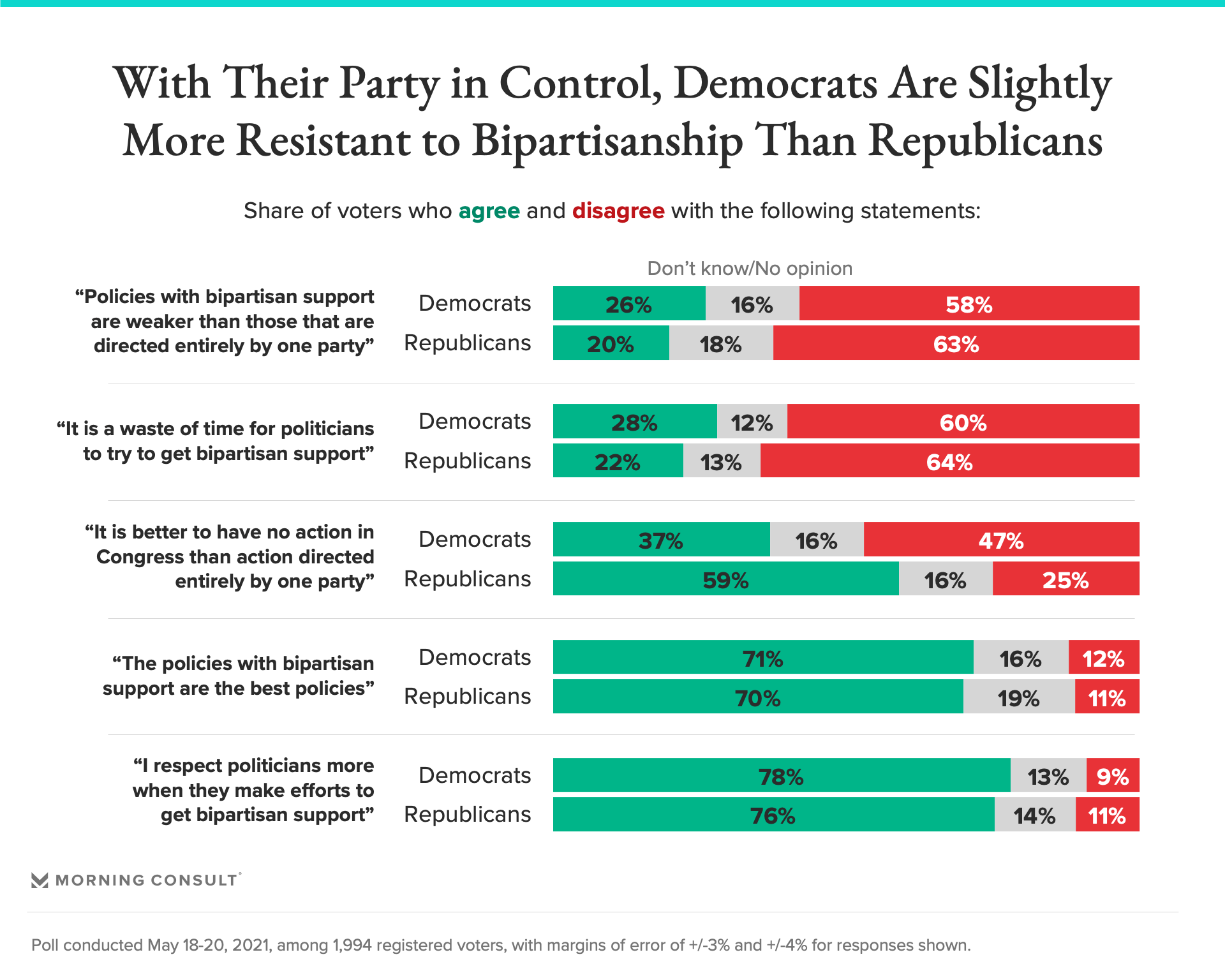

Biden’s effort to secure Republican backing for his infrastructure legislation – or to at least give the impression that he’s interested in a bipartisan package – is in line with conduct that is viewed as noble by the electorate: More than 3 in 4 Democrats and Republicans say they “respect politicians more when they make efforts to get bipartisan support.”

Manley cast Biden’s bipartisan overtures in the infrastructure debate as delivering on a campaign promise to try to work with Republicans in a country so politically divided. While previous polling has found voters are only slightly more likely to see Biden as moderate than they are House Democrats, the latest survey showed more than half of voters believe him when he says he wants to cut a deal with Republicans.

Fifty-three percent agreed that Biden cares about getting bipartisan support for major pieces of legislation, and a plurality (46 percent) say the same of Democrats in Congress. On the other hand, almost half disagreed that Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) or Republicans in Congress are interested in the concept.

Tactically, Manley said Biden’s show of bipartisanship is about “building up a comfort level” among moderates such as Sens. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.), whom he’ll need to get his agenda through the Senate in the face of anticipated Republican opposition.

“The president has been more than willing to give them the time they’ve asked for to try to negotiate, but it sure looks to me that he’s willing to pull the trigger and move under reconciliation if he needs to,” he said.

The reconciliation option would avert a Republican blockade via the legislative filibuster and allow Senate Democrats to pass Biden’s proposal if all 50 of them are on board. But the move would also require the White House to rely on its old definition to cast the moves as bipartisan, which might be a tougher sell this time around, given the weaker backing among Republican voters for his infrastructure proposals than it had for the COVID-19 relief package.

Republican strategist Ron Bonjean said that could spell political peril for the party in power.

“Jamming them through the reconciliation process instead of coming to a bipartisan consensus means that the Democratic Party would take the entire blame should the American people react negatively to poor implementation and management in the long term,” he said.

Voters of both parties largely share the view that bipartisan bills result in the best policy, but the survey suggests there are limits to the patience of Democratic voters, reflecting the increasing sense of urgency from many Democrats on Capitol Hill.

Roughly 3 in 10 Democratic voters say it’s a waste of time for politicians to try to get bipartisan support, higher than the share of Republicans who said the same, and they are nearly twice as likely their GOP counterparts to disagree with the statement that it’s “better to have no action in Congress than action directed entirely by one party.”

Voter sentiment about bipartisan action isn’t limited to infrastructure or social spending: On a range of issues – including immigration, taxes, guns and even voting rights – roughly 7 in 10 Democratic and Republican voters said action in Congress should be bipartisan, and roughly 3 in 5 Democratic and Republican voters said they view it as “very important” that legislation generally has bipartisan support.

“With such narrow margins of House Democratic control, bipartisan backing of legislation should matter especially to moderate Democrats in red districts so they can show their voters that working with Republicans and generating solutions for the good of the country,” said Bonjean, who worked for Republican leaders on Capitol Hill during the 2000s.

But even simple issues, such as an uncontroversial bill meant to help more opioid treatments go to market, have gotten caught up in wrangling between the two parties – not over whether Democrats should work with Republicans, but which ones.

Nearly 150 Republican lawmakers – 139 in the House and eight in the Senate – backed former President Donald Trump’s effort to overturn election results on Jan. 6. While the majority of Democratic voters believe those lawmakers should be ostracized, the position is not popular with the larger electorate.

A plurality of voters (46 percent) -- including nearly a third of Democrats -- say Democrats in Congress should work on legislation with Republican lawmakers who voted to challenge the 2020 presidential election results, while 38 percent of voters say they should not, driven by nearly 3 in 5 Democratic voters.

Eli Yokley is Morning Consult’s U.S. politics analyst. Eli joined Morning Consult in 2016 from Roll Call, where he reported on House and Senate campaigns after five years of covering state-level politics in the Show Me State while studying at the University of Missouri in Columbia, including contributions to The New York Times, Politico and The Daily Beast. Follow him on Twitter @eyokley. Interested in connecting with Eli to discuss his analysis or for a media engagement or speaking opportunity? Email [email protected].

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade