‘It’s What We Call Reverse Redlining’: Measuring the Proximity of Payday Lenders, Pawn Shops to Black Adults

The data in this article is drawn from a poll of 2,000 Black adults, gauging attitudes on a variety of social, political and economic issues.

As the Black Lives Matter movement highlights the ways that racial inequality is deeply etched in Black neighborhoods, financial policy and consumer advocates have been calling attention to the targeting of Black Americans by high-interest, short-term lenders, such as pawn shops and payday lenders, as one of the most pervasive.

Regulators in the Trump administration are making it easier for payday lenders to exploit Black communities, consumer advocates say, pointing to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s elimination of the “ability-to-repay” payday lending rule, which required that these lenders ensure borrowers have the means to repay a loan. Consumer advocates, who say these loans are predatory, argue that the CFPB’s rollback makes it easier for these lenders to trap borrowers in a cycle of debt.

New Morning Consult data highlights the ongoing issue that consumer advocates and some financial regulators are trying to address — the prevalence of high-cost, low-quality financial services in Black communities.

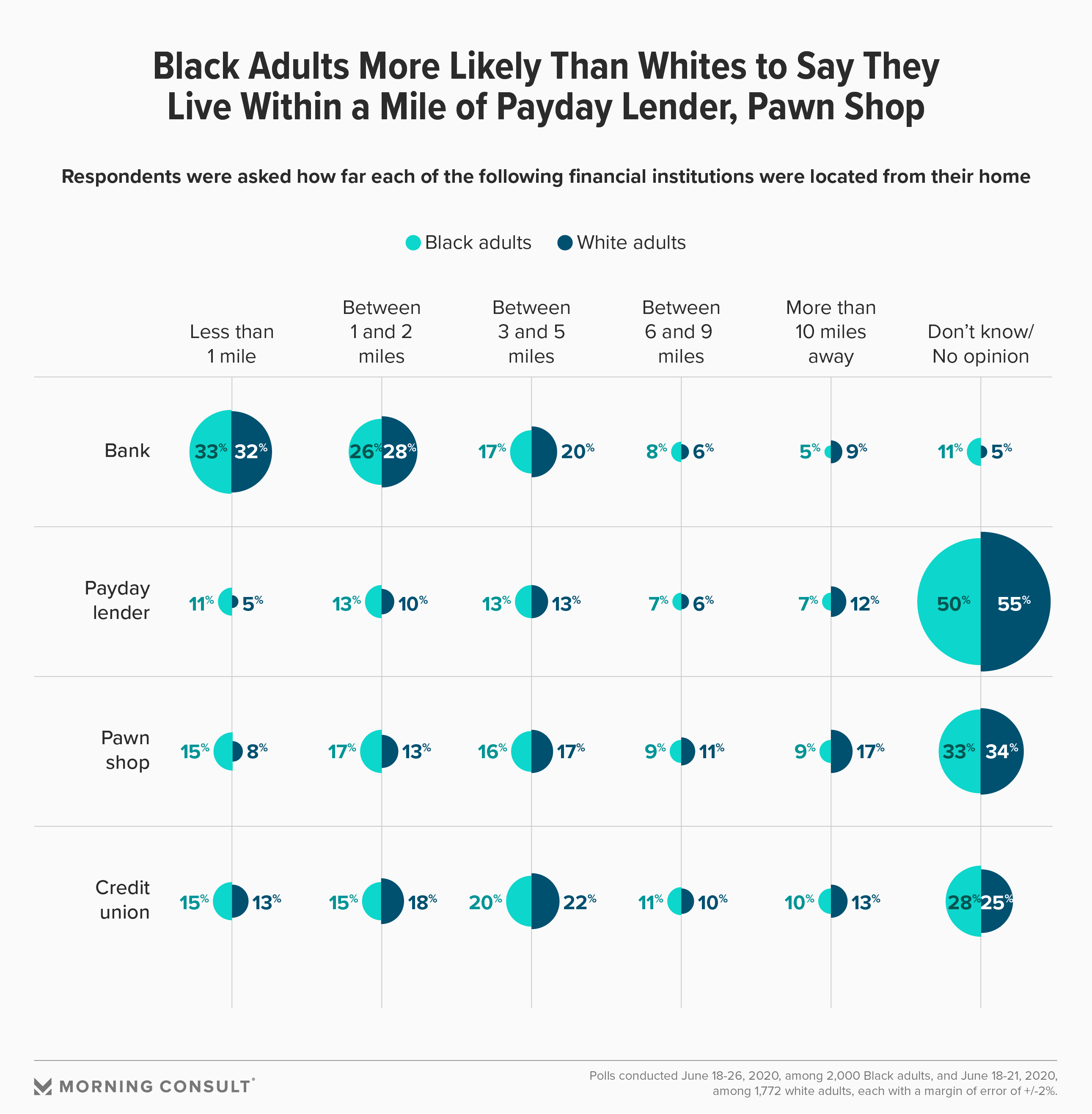

Black adults (11 percent) are 6 points more likely to say they live within a mile of a payday lender than white adults (5 percent), according to the data. Black adults (15 percent) are 7 points more likely to say the same about a pawn shop, which can also be used as a quick but pricey way to get a small loan, compared to white respondents (8 percent).

The data is pulled from two polls: One surveyed 2,000 Black adults from June 18-26, and the other 2,200 U.S. adults, which includes 1,772 white adults, from June 18-21. Both have margins of error of 2 percentage points.

Those figures narrow in the middle distances (between 1 and 2 miles, and between 3 and 5 miles). White adults were more likely to say they lived more than 10 miles away from payday lenders (by 5 points) and pawn shops (by 8 points).

“Payday lenders and pawn shops are an extremely high-cost way to borrow money,” said Jesse Van Tol, chief executive of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, a grassroots coalition that advocates for equal access to banking services, housing and other financial services. “Targeting people of color for higher-cost products, it’s what we call ‘reverse redlining.’”

The topic of unequal access to financial services is being discussed more now not just because of the upheaval around police killings — it’s also increasingly important as the economy falters from the coronavirus pandemic, putting thousands out of work and hitting Black communities particularly hard.

“Especially now, with the COVID-19 crisis, we know that payday lenders have marketed themselves as friendly neighborhood figures in Black and low-income communities,” said Charla Rios, a researcher at the Center for Responsible Lending focusing on payday lending and predatory debt practices. “It’s things like that that exacerbate the racial wealth gap.”

In a statement to Morning Consult, the Community Financial Services Association, the trade group that represents payday lenders, said that without alternative financial services, their customers would not have access to short-term, small-dollar credit.

“We are located in communities across the country, including those that are often not served or are underserved by banks,” said D. Lynn DeVault, Chairman of CFSA. “By being close to our customers, we get to know them on a deeply personal level and understand their financial needs.”

The National Pawnbrokers Association did not respond to a request for comment.

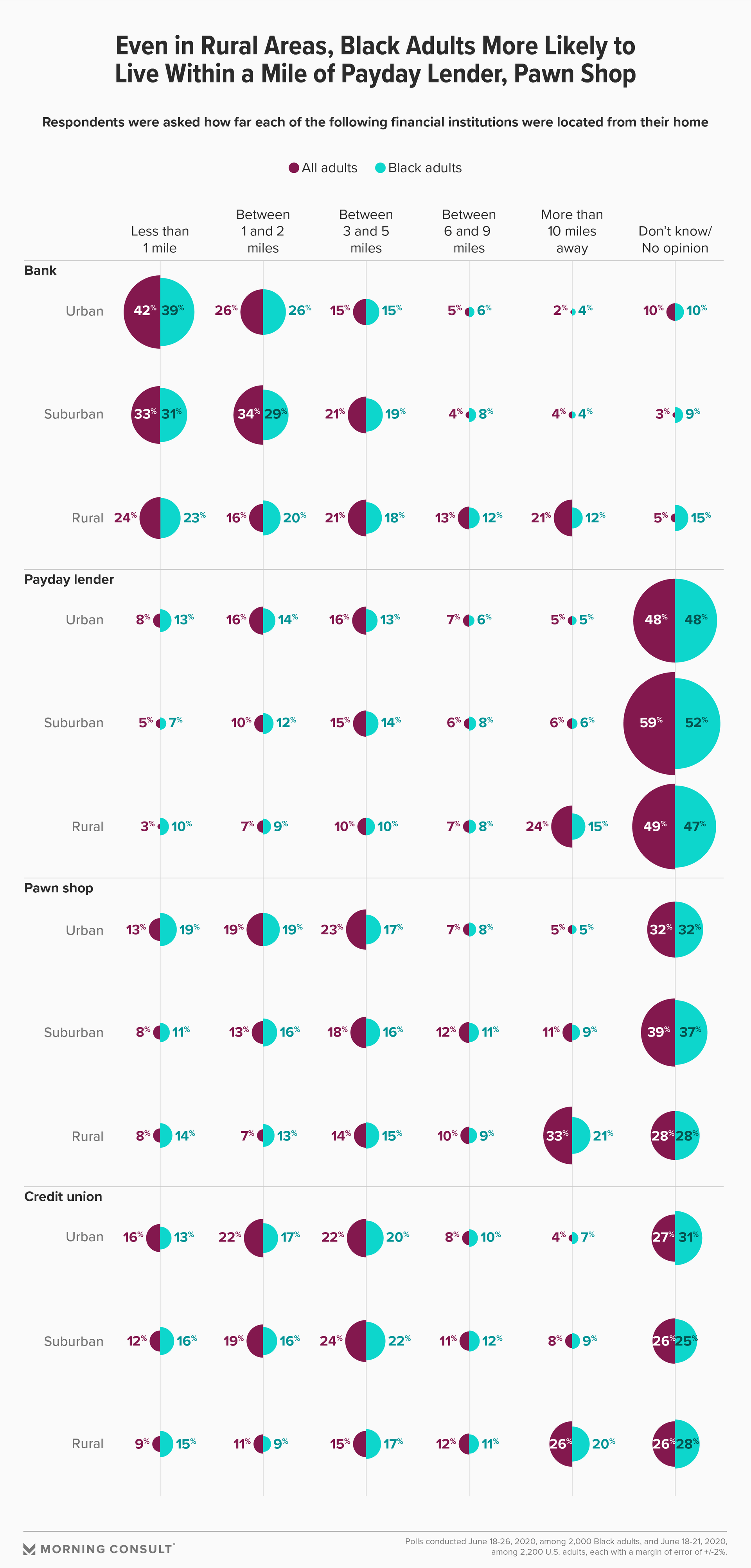

Historically, data about proximity to financial services has been skewed by the fact that Black people are more likely to live in urban areas compared to whites. A Black person who lives in an urban area, for example, is more likely to live within a few miles of a bank branch than anyone of any race is in a rural area.

“A mile in a city is a lot different than a mile in a rural area,” said Terri Friedline, a professor of social work at the University of Michigan who studies financial system reform and consumer protections. “There’s levels of scale that mean different things in different geographic areas.”

Morning Consult broke down the data by urban, rural and suburban respondents to get a better understanding of financial services in Black communities across the board.

In urban areas, 13 percent of Black adults said they live within a mile of a payday lender, and 19 percent said the same about a pawn shop. That’s compared to 8 percent of all adults in an urban area who said they live within a mile of a payday lender and 13 percent for pawn shops.

The trend is the same for rural respondents: 10 percent of Black adults who said they live in a rural area also said they live within a mile of a payday lender, compared to 3 percent of all rural adults. Fourteen percent of rural Black adults said they lived within a mile of a pawn shop, compared to 8 percent of all rural adults.

This is especially striking because payday lenders and pawn shops are thought of as less common in rural areas, Friedline said.

“So even in rural areas where population density is lower, payday lenders and pawn shops will still target in a predatory way, Black and brown communities,” she said.

Across urban, rural and suburban communities, there’s not a big difference between the answers of all adults and Black respondents in proximity to banks. Credit unions, which can offer short-term small loans at a better price than a payday lender or a pawn shop, vary in proximity to different communities.

During the Trump administration, some bank regulators have suggested that allowing banks to offer small-dollar loans could offer those who need a small amount of credit another option — an idea that Obama-era regulators largely eschewed. In March, as the COVID-19 crisis led to the shutdown of much of the U.S. economy, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and other regulators released guidance allowing banks to provide small-dollar loans.

Regulatory leaders have also recently proposed ways to remedy economic inequality. In an interview this month, Brian Brooks, head of the OCC, said that easing regulatory hurdles for financial technology firms could increase low-income and Black communities’ financial service options, while FDIC Chairman Jelena McWilliams has called for changes to encourage bank to give out small-dollar loans.

Still, consumer advocates don’t think these measures go far enough or are counterproductive. Van Tol said that fintech products could prove to be just as predatory if not regulated properly, and Friedline said that digital banking efforts won’t go far in rural areas, where internet access and phone service is a major issue.

And while banks typically offer better terms on loans than, say, a payday lender, they still have some predatory products and can be discriminatory, Friedline said.

“There’s a continuum of racialized financial services, so banks do things that are predatory, too,” she said. “Ultimately, things like redlining predatory contract agreements, segregation and even bombings in the ’50s and ’60s has forced Black and brown people into these precise, geographically defined communities, which makes it easier for payday lenders, pawn shops and other financial services to target them.”

Claire Williams previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering finances.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade