Energy

The Clean Energy Workforce Was Projected to Grow 5.3% in 2020. Instead, It Has Shrunk 13.8%

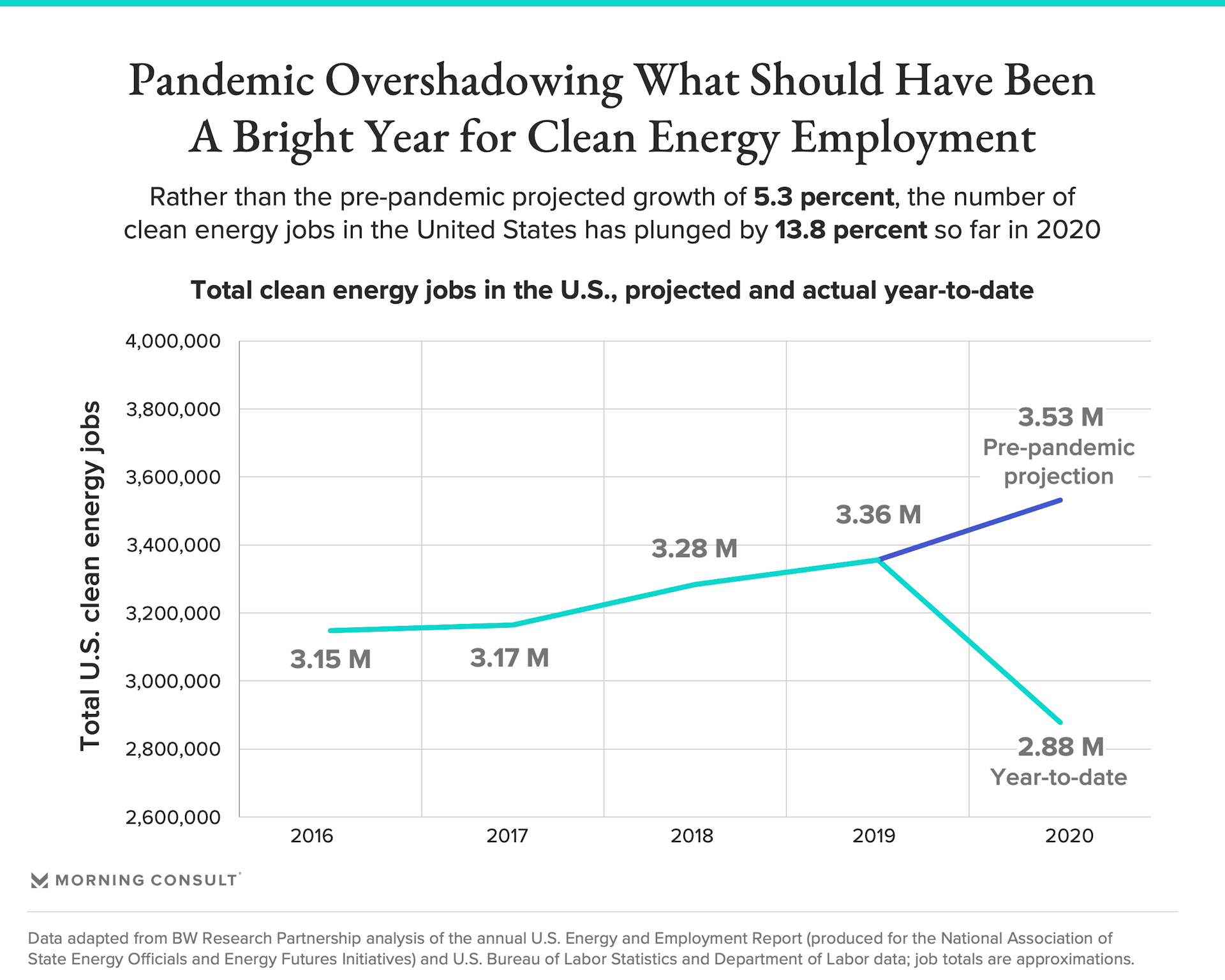

The arrival of the coronavirus in the United States arrested the growth that the country’s clean energy sector could have seen in 2020, causing a deficit so far of approximately 655,000 jobs compared with pre-pandemic projections.

According to data collected by BW Research Partnership Inc. and shared exclusively with Morning Consult, the United States was expected to see accelerating growth in clean energy employment in 2020: a rate of 5.3 percent in the 2019-20 period compared with the 2018-19 rate of 2.2 percent. This could have amounted to approximately 3.53 million jobs nationwide, predominately in energy efficiency.

However, when the pandemic took hold earlier this year, this optimistic picture faded quickly. While clean energy employment has recovered somewhat since its May low point of more than 620,000 jobs lost, the latest data shows that the sector still faces a deficit of 477,862 jobs compared with the pre-pandemic baseline. The sector’s employment now hovers around 2.88 million jobs, amounting to a fall of 13.8 percent since the beginning of the pandemic.

This drop-off is particularly dramatic when considering that the most job losses took place in the sunny spring months when the seasonality of the clean energy sector would typically mean more hiring, said Philip Jordan, vice president of BW Research and the author of the firm’s monthly clean energy employment reports since the start of the pandemic.

“At the pace at which these industries have been growing historically, and the fact that expectations tend to hover between 4 and 6 percent, getting back to where they were in the fourth quarter of 2019 is still down a lot of jobs versus where they could have been,” continued Jordan. “It’s not just the jobs lost and the jobs bouncing back; there was an expectation and there has been historic precedent for significant job creation in this sector.”

Pre-pandemic projected growth was particularly high in Missouri (8.7 percent), North Carolina (7.6 percent) and Rhode Island (7.5 percent). Instead, the latest jobs report finds that both North Carolina and Rhode Island are facing above-average job losses in the clean energy sector since the start of the pandemic, with declines of 17 percent and 19.4 percent, respectively. Missouri’s losses are just below the 50-state average, at 12.6 percent.

Asked whether those in clean energy should be optimistic given the state of employment in the sector, Jordan was contemplative, weighing both the industry’s potential tailwinds — such as state policies from governors and legislatures in states like California and New York doubling down on clean energy and climate initiatives — and major uncertainties. These include the path of the virus itself and vaccine development, the election results in November and the stability of the country’s economic outlook.

“My best guess is that we’ll be in a holding pattern for a while, but the potential for falling off a cliff if things go the wrong way is pretty strong,” Jordan said. But alternatively, if Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden is elected and enacts his proposed climate and energy investments to the tune of $2 trillion over his first term, “there’s the potential for a pretty strong rebound.”

BW Research has been contracted by Environmental Entrepreneurs (E2), E4TheFuture and the American Council on Renewable Energy to conduct the monthly analyses of pandemic-related job losses through the end of 2020, which rely on data from BLS and the Department of Labor.

Meanwhile, the pre-pandemic data and projections come from the annual U.S. Energy and Employment Report, using the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages as well as a supplemental survey of 30,000 business representatives conducted by BW Research. (It should be noted that the 2016 data was compiled using an earlier methodology and has not been updated to match the methodology that the organization has used since 2017, so the resulting aggregates cannot be compared perfectly.)

The Department of Energy commissioned the 2015 USEER, though the agency stopped its involvement in 2017 and the National Association of State Energy Officials and Energy Futures Initiative have stepped in to work with BW Research in compiling this data ever since. DOE is supposed to recommission the report in early 2021 regardless of the results of the presidential election next month, though so far “there’s just apparently been no movement” communicated by the administration to make that happen, said Michael Timberlake, communications director for E2.

DOE had not responded to a request for comment about its plans for the planned 2021 USEER at the time of publication.

Correction: This story previously contained old figures from Joe Biden's clean energy investment plan. It has been updated with the new terms.

Lisa Martine Jenkins previously worked at Morning Consult as a senior reporter covering energy and climate change.