Study Shows Health Care Prices Have Risen While Previous Insurance Coverage Has Leveled Off

High prices, widening gaps in insurance coverage and racial disparities in outcomes are tied to wide state-level variation in health care performance that will likely be exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic, according to a sweeping new report from The Commonwealth Fund.

The analysis, which assessed all 50 states and the District of Columbia on dozens of measures tracking health care quality and costs, health outcomes and disparities, indicates Americans’ health care burden and risk of poor health varies widely based on where they live. While the data predates the COVID-19 crisis, researchers said the pandemic could worsen these state-level disparities, “leaving people in poorly performing states even further behind.”

The report notes a few key issues: Because most Americans get their health insurance through an employer, recent job losses are estimated to leave 3.5 million people uninsured by the end of the year, according to an Urban Institute analysis, widening existing coverage gaps. Rising provider prices have led to higher costs for people with private insurance because employers tend to pass premium increases on to employees. And U.S. life expectancy, which has fallen in recent years, is closely tied at the state level to premature deaths from treatable conditions like appendicitis, certain cancers, heart disease and diabetes — which Black Americans have twice the risk of dying from as whites.

“There's little doubt that the pandemic has exacerbated these and other weaknesses in our health care system,” Dr. David Blumenthal, president of The Commonwealth Fund, said during a call with reporters.

Despite health insurance gains in the years following the Affordable Care Act’s passage — which is also credited with shrinking racial and economic disparities in health coverage — access to care remains a critical problem, the report shows. From 2016-18, 22 states saw increases in the share of adults without health insurance, and uninsured rates in the 12 states that have not expanded Medicaid eligibility were among the highest in the country in 2018.

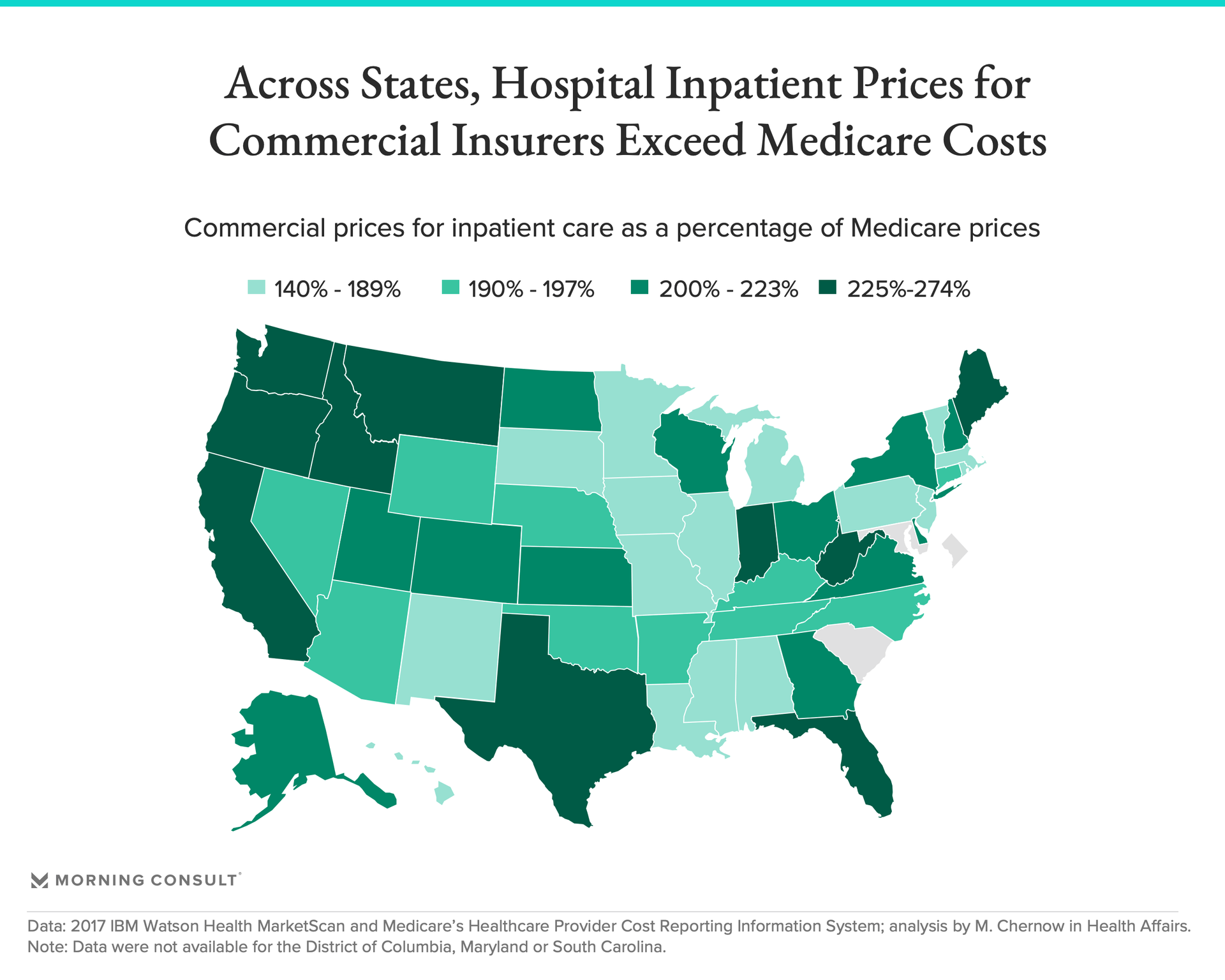

People who have insurance can face steep health care costs, as well. Commercial insurance prices for hospital inpatient care were at least twice as high as Medicare rates in 22 states, the report said, while people reported delaying care due to costs in 15 states.

“These higher prices have consequences,” said Dr. David Radley, a senior scientist for The Commonwealth Fund and one of the report’s authors. Higher health care prices essentially burden “working families with higher premium contributions and unaffordable out-of-pocket costs.”

Investment in primary care — one way to improve health care performance, researchers said — is also lower in the United States than in other wealthy countries. For example, just under 6 percent of spending on Medicare patients went to primary care in 2017 — amounting to about $712 per beneficiary annually — with rates ranging from less than 5 percent in Rhode Island and New Hampshire to more than 7 percent in Tennessee.

Overall, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Iowa and Connecticut performed best in The Commonwealth Fund’s state ranking, while West Virginia, Missouri, Nevada, Oklahoma and Mississippi scored worst, and Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana and Virginia improved the most between 2014 and 2018.

If all states’ metrics matched the highest-performing state for each of the report’s 49 measures, researchers estimated it would lead to 91,000 fewer deaths before the age of 75 from treatable conditions, 10 million fewer emergency room visits for health issues that could have been treated in non-emergency care and 18 million more adults and children with health insurance in addition to those who already have ACA coverage.

As is, the report concludes that the U.S. health care system is “highly unequal in its care of people of color and those with low and moderate incomes,” and says national averages mask the fact that some parts of the country lag behind not only other states, but other developed countries.

Gaby Galvin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.