The Public’s Willingness to Get a Coronavirus Vaccine Ticks Up Slightly With Promising Developments and Surge in Cases

Key Takeaways

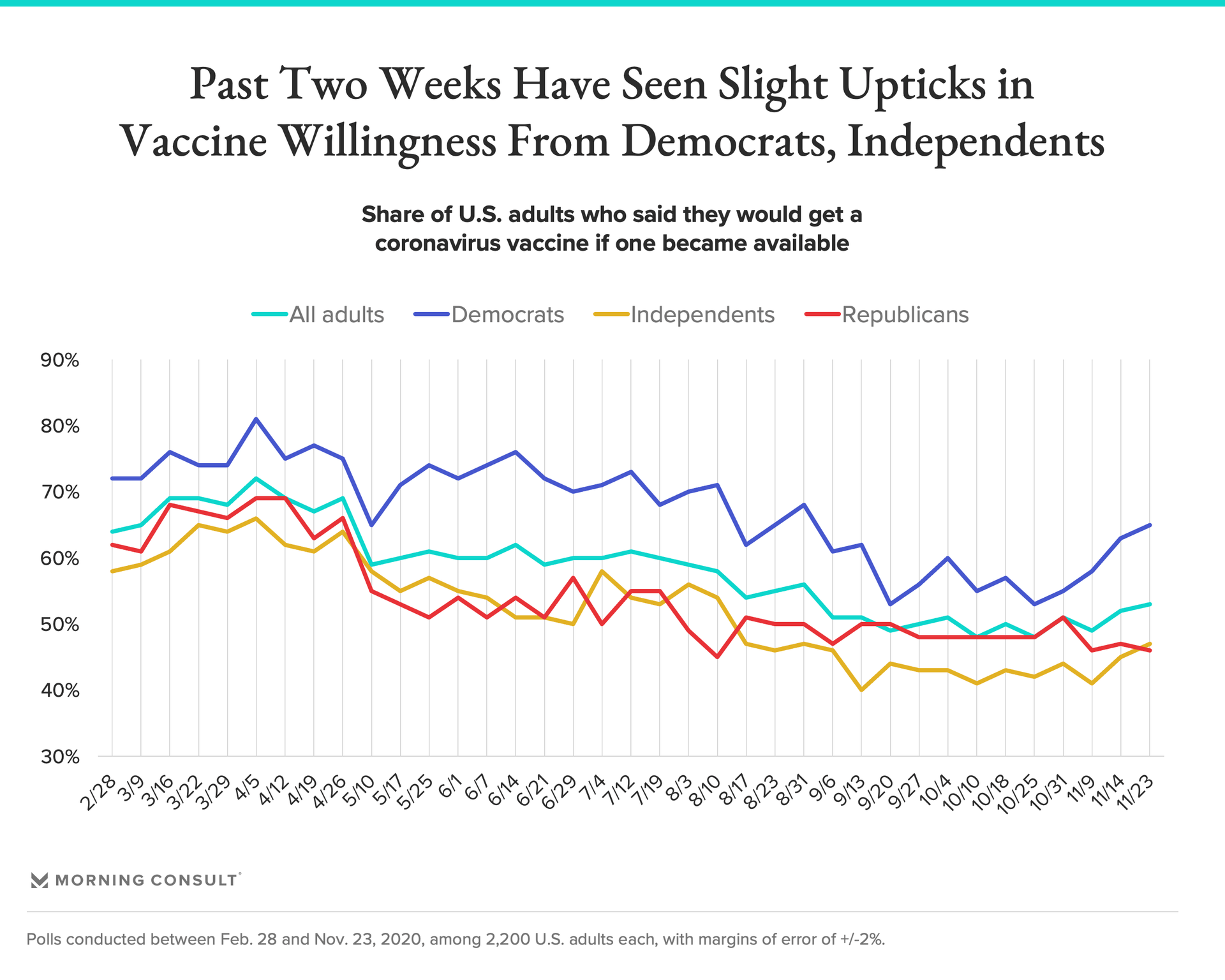

53% of adults say they’d seek a coronavirus vaccine if one were available, up from 49% earlier in November.

Democratic adults are 19 percentage points more likely than Republicans to say they’d seek a vaccine, 65% to 46%.

Americans are more likely to say they’d get vaccinated against the coronavirus than they have been in nearly three months, but willingness remains driven largely by political leaning.

Fifty-three percent of adults now say they would get a coronavirus vaccine if one became available, according to a new Morning Consult poll, a slight uptick from 49 percent the first week of November and the highest level since late August, amid both a surge in infections that’s threatening to overwhelm health systems and a flurry of promising vaccine developments.

Meanwhile, 23 percent of adults said they would not get vaccinated and another 23 percent didn’t know or had no opinion, according to the survey, which was conducted Nov. 19-23 among 2,200 adults and has a margin of error of 2 percentage points.

“The fall was very challenging, with a lot of political debate and discussion around vaccine timing, and I think that drove down overall confidence,” said Dr. Mark McClellan, the former Food and Drug Administration commissioner who directs the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy. “What's important for influencing confidence for everyone is their confidence in the FDA.”

The small climb in vaccine willingness may be a reflection of the news of the past two weeks: Pfizer Inc. and BioNTech SE said their coronavirus vaccine candidate was 95 percent effective and applied for emergency authorization from the FDA, while Moderna Inc. also announced its vaccine was highly effective in a late-stage trial and is expected close behind in its pursuit of FDA sign-off. AstraZeneca PLC, which developed its vaccine with the University of Oxford, reported promising early data for older adults last week and more complete data on its vaccine hopeful Monday.

In a separate Morning Consult/Politico poll over the weekend, 70 percent of adults reported seeing, reading or hearing a lot or some about the efficacy of Moderna’s vaccine, and 72 percent said the same about Pfizer’s applying for an emergency use authorization.

“All of these things are going to cause ups and downs,” said Dr. Emily Brunson, an anthropologist at Texas State University whose current research focuses on coronavirus vaccination among college students and in Black and Latino communities.

Yet the findings also reflect the politicization of the vaccine process and the pandemic as a whole, Brunson said. “In the modern public health era, we haven't ever had a situation that's equivalent.”

In the latest survey, Democrats were 19 points more likely than Republicans to say they’d get a vaccine, 65 percent to 46 percent, the widest the vaccine willingness gap has been since August. Compared to late October, Democrats are 10 percentage points more likely to say they’d seek a vaccine, while Republicans are 5 points less likely to say the same.

The partisan gap could narrow in the coming weeks as outside experts make recommendations about whether a vaccine candidate should be authorized and who should be prioritized to receive it, McClellan said. An FDA advisory committee is set to meet Dec. 10 to discuss Pfizer’s vaccine candidate.

“I think those kinds of nonpolitical events could have more of an across-the-board impact on vaccine confidence,” he said.

Yet other major gaps in vaccine willingness remain. Women, people without a college education and those in rural areas remain less likely to say they'd get a vaccine, according to the survey, while other research indicates a deep lack of trust among Black and Latino communities in any eventual vaccine’s safety and effectiveness.

And while public health officials can draw on broader health care trends and lessons from past vaccination efforts, such as for the H1N1 swine flu, it will be critical to understand the particular social dynamics of coronavirus vaccine willingness in order to immunize broad swaths of the country, Brunson said.

“This has been such a technological achievement, to actually get vaccines done this quickly,” Brunson said. “You can have the most perfect vaccine and the most perfect delivery system possible, but if no one wants to take the vaccine, it really doesn't matter.”

Gaby Galvin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade