One Year and 400,000 Deaths: How the Pandemic Divided America

A year ago, the disease didn’t even have a name. Today, it’s a leading cause of death in the United States.

On Jan. 21, 2021, one year after federal health officials announced they had identified the nation’s first known coronavirus infection in a man from Washington state, the virus has seeped into every corner of the country, and Americans are deeply divided on everything about it — from how leaders have handled the pandemic to whether they plan to get vaccinated or even wear a mask.

The year ahead will be marked by challenges of its own, as the death toll climbs even as millions of people get vaccinated, and as new coronavirus variants thrust the country into a level of unknown reminiscent of when the virus first emerged as a mysterious pneumonia in China in late 2019.

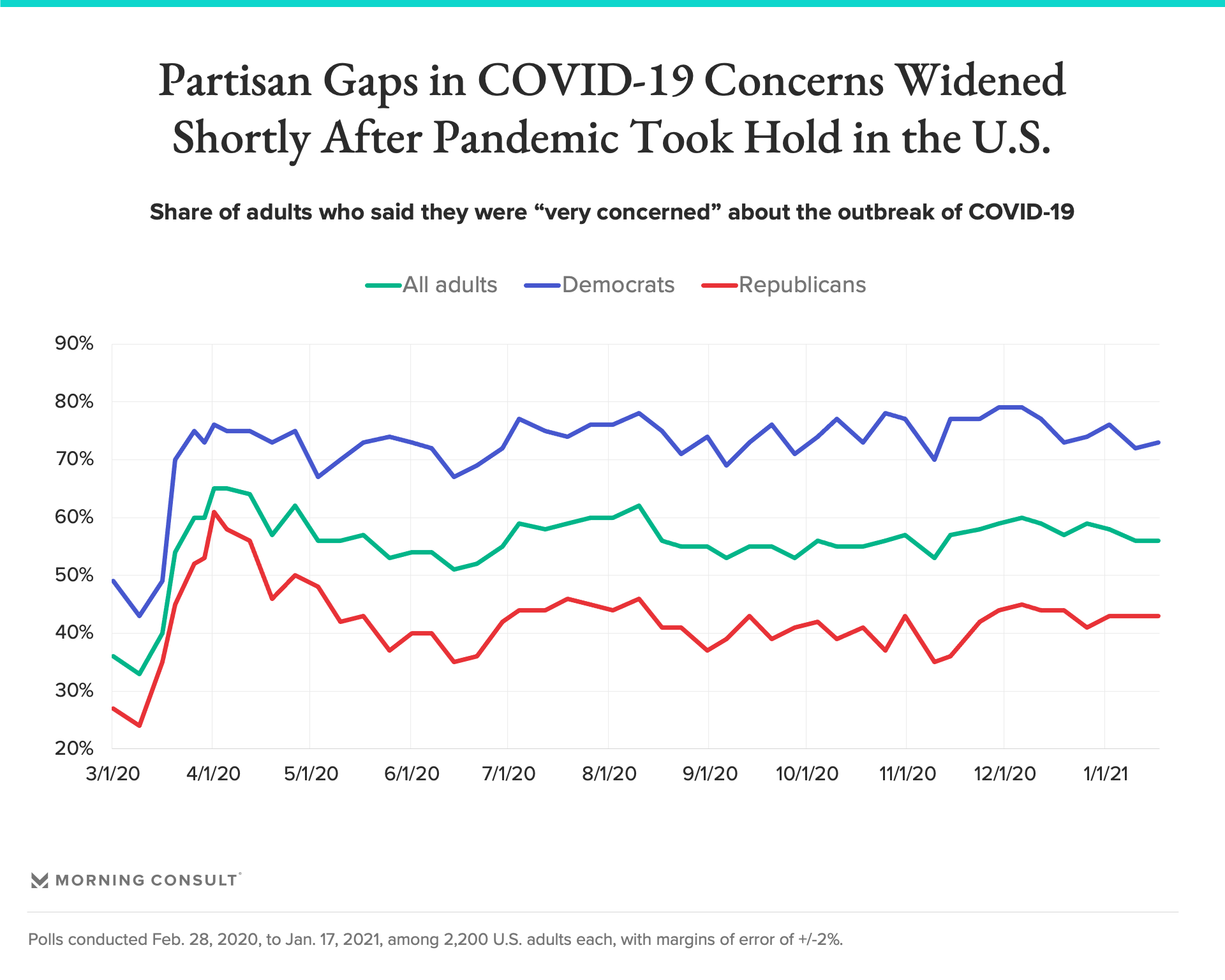

Morning Consult data indicates that while the pandemic’s partisan splits have grown worse over the last year, they’ve been there from the beginning. In the first poll on the virus conducted Jan. 24-26, 2020, 32 percent of adults, including 38 percent of Democrats and 29 percent of Republicans, were very concerned about the outbreak. By Jan. 15-17, 2021, the most recent survey, 56 percent of adults were very concerned about COVID-19, but the party gap was 21 percentage points wider.

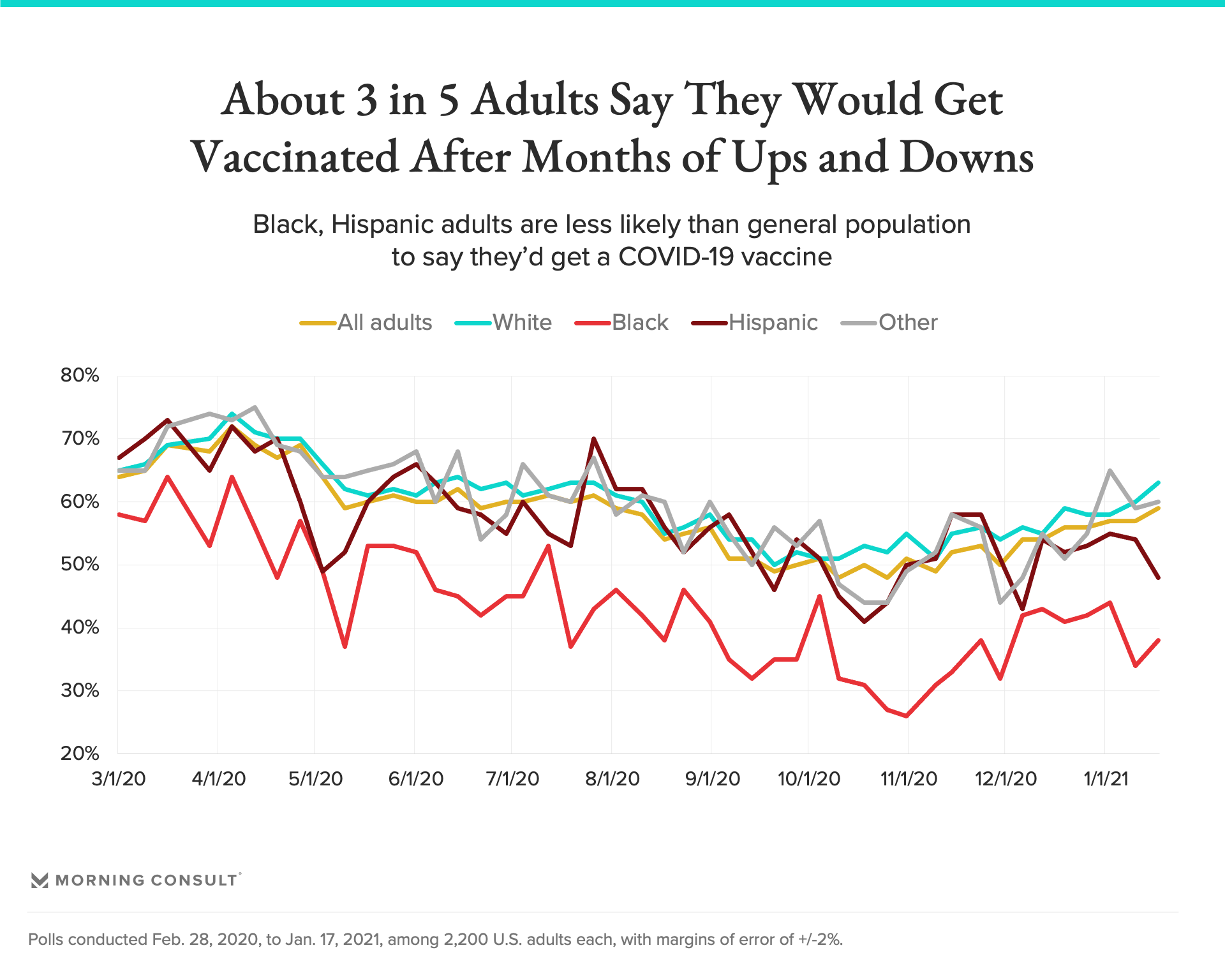

The divides aren’t just political, either, with women, people in rural areas and Black Americans all less likely to say they’d get vaccinated and older adults much likelier than those in Generation Z to say they’re very concerned about COVID-19.

To some degree, the divisions were inevitable, with vaccine hesitancy, online misinformation and political tribalism blending together in a toxic stew, current and former health officials, health policy observers and behavioral scientists say. But the overt politicization of the pandemic response, including mixed messages from the White House and its timing in a contentious election year, undoubtedly made the divisions — and the pandemic itself — worse.

“In any situation, you need clear and consistent messaging, you need clear and consistent guidance,” said Dr. Nicole Lurie, who has advised President Joe Biden on COVID-19 and previously served as assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the Department of Health and Human Services during the Obama administration. “And instead, I think building on this climate of fake news and continuing to divide the country, you then had almost pretty deliberate denial and confusing communication around it.”

A year of survey data reveals the moments that mattered to the public, as well as those that didn’t. For example, in what was perhaps the starkest warning yet of COVID-19’s potential impact, Dr. Nancy Messonnier, a senior official at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, cautioned in late February that “disruption to everyday life may be severe.” The markets stumbled, reportedly angering President Donald Trump, and leadership of the White House coronavirus task force shifted the next day from Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar to Vice President Mike Pence.

But the public’s concern over the virus didn’t begin climbing until mid-March, around the time the number of cases identified every day began surging in the Northeast and the White House asked Americans to stay home for 15 days to “slow the spread.” By April 1, 65 percent of adults were very concerned about the outbreak — a high point in Morning Consult polling — and the gap between Republicans and Democrats was 15 percentage points. Yet just one month later, even after the country’s COVID-19 death toll had doubled in nine days, overall concern had dropped 9 points, but the partisan split was 4 points wider.

“We know so much more about the virus now than we did earlier,” said Dr. Kameron Matthews, chief medical officer at the Veterans Health Administration. But “I think it is very easy for the public not to trust a changing environment.”

The next months were a pandemic blur — Trump repeatedly claimed that the virus would soon “disappear”; health care workers donned trash bags as protective gear; Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, ascended to pop culture stardom; Americans stayed home and then didn’t; the United States began its withdrawal from the World Health Organization; concern over political interference at federal health agencies grew; talks for additional pandemic relief stalled and then passed in Congress; Trump got COVID-19 and lost re-election; two vaccines were authorized in record time and the first medical workers got their shots; and just yesterday Biden took office, signaling a shift in the federal pandemic response.

Through it all, COVID-19’s death toll climbed, reaching 400,000 this week, with Black, Indigineous and Latino communities bearing the brunt of the pandemic’s devastation.

Those months were also marked by a seesaw of overall concern about COVID-19 and widening gaps by political affiliation, race and other groups. For example, voters’ net approval of Trump’s handling of the pandemic reached what was then a low of minus-21 on Aug. 10, but remained relatively stable among Republicans at plus-62.

The share of Black adults who said they’d get a COVID-19 vaccine reached a low of 26 percent Oct. 31 — and as of Jan. 17, had only climbed back to 38 percent, compared to 63 percent among white adults. And Trump’s most ardent supporters were consistently the least likely to believe in the effectiveness of masks, with that share nosediving after a general consensus among adults of all political backings earlier in the spring.

“We have seen what happens when you have this information vacuum that's filled with cluttered, inconsistent strategies,” said Dr. Jason Schwartz, an assistant professor at the Yale School of Public Health.

Now, as Biden assumes the White House and new coronavirus variants insert another layer of uncertainty into the year ahead, federal officials face the daunting task of both cooling the political temperature around the pandemic while distilling the importance of following public health guidance and mounting a significant pandemic response.

Biden, who said last week that it was “stupid” that face coverings had become a political issue, is pushing Congress for $415 billion to ramp up the federal COVID-19 response as part of a $1.9 trillion pandemic relief plan, and plans to launch a locally tailored public education campaign to address vaccine hesitancy.

In such a politically tense moment, it will be just as important to address people’s core beliefs as it will be to get them scientifically sound information, said Dr. Panayiota Kendeou, an educational psychologist at the University of Minnesota whose recent work has focused on COVID-19 vaccine misinformation. She said public health efforts should focus less on swaying “hardcore vaccine deniers” and more on those who are unsure or confused about the process.

Schwartz, meanwhile, said the administration should bring nonpolitical public health leaders to center stage: “We need to hear less from elected officials with D or R next to their name.”

Gaby Galvin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade