Western Countries View COVID-19 and the Spread of Infectious Diseases as Major Threats

Key Takeaways

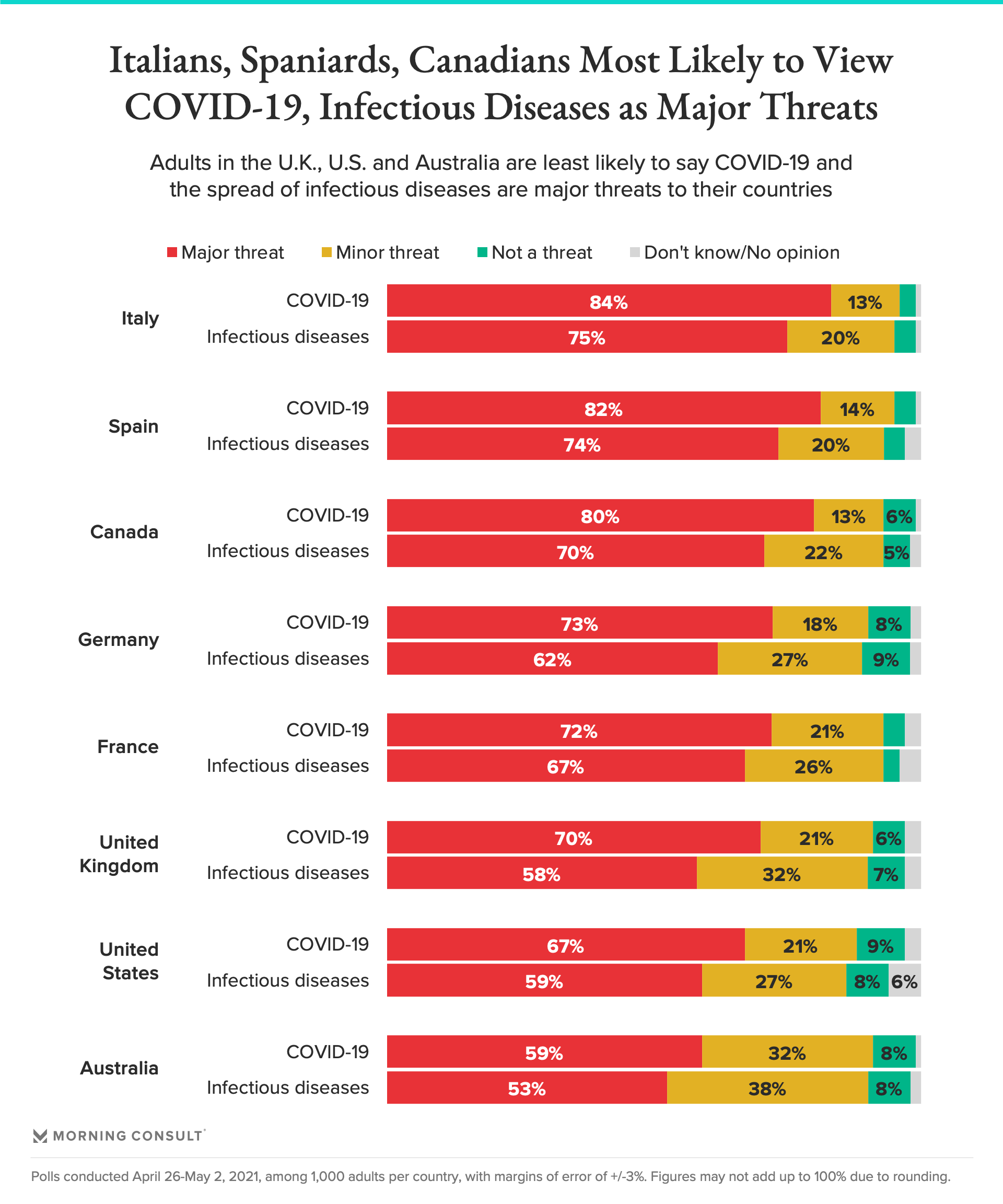

84% of Italian adults said COVID-19 is a major threat to the country, compared with 67% of American adults.

Across the eight countries surveyed, between 53% and 75% of adults said the spread of infectious diseases is a major threat.

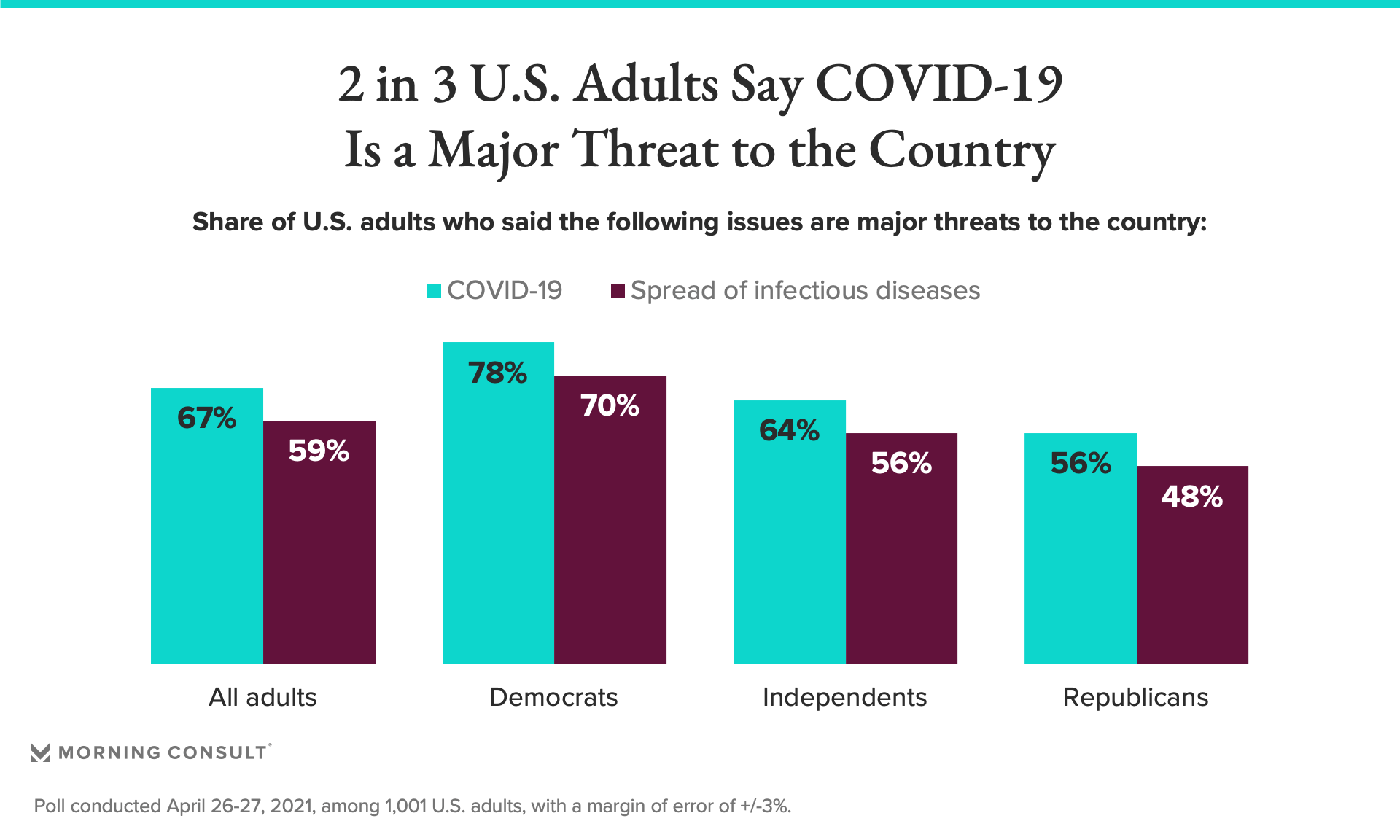

In the United States, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to cite COVID-19 and the spread of infectious diseases as major threats to the country.

The COVID-19 pandemic has reached an inflection point: In countries like the United States, where more than 60 percent of adults are at least partially vaccinated and shots are widely available, residents are beginning to return to their routines and navigate life post-pandemic. Yet other nations remain firmly in COVID-19’s grip, and the global crisis is far from over.

As the international community grapples with the next stage of the pandemic and beyond, new Morning Consult polling indicates that in seven of eight Western countries surveyed, at least 2 in 3 adults say COVID-19 is a major threat to their nations. At least half of adults in the eight countries say the same of the spread of infectious diseases in general.

Public perception varies by country. In Italy, for example, 84 percent of adults said COVID-19 is a major threat to the country, while 80 percent of Canadians and 73 percent of Germans said the same of their own nations. In the United States, that share was 67 percent.

Across countries, adults were more likely to say COVID-19 is a major threat than the spread of infectious diseases in general. But the large shares who say both issues are top threats is unsurprising, global health analysts said, given most countries are still grappling with the pandemic’s impact on daily life. They said overall concern in developed countries will likely fall as their vaccination efforts continue, and that now is the time to prepare for the next global health crisis.

“If we don't capitalize on the present moment, we may be subject to that cycle of panic and neglect that often is the hallmark of infectious disease threats,” said Kate Dodson, vice president for global health strategy at the United Nations Foundation.

Dr. Mario Ramirez, an emergency physician and a law firm consultant, pointed to the 2014 Ebola outbreak, which highlighted the country’s lack of preparedness for a health security emergency. Yet because the United States was spared the kind of devastation Ebola wrought on West Africa, U.S. resources to combat domestic health threats quickly dropped off, he said.

“There is immense pressure to respond to public opinion and the emergency that's right in front of you,” said Ramirez, who worked on emerging threats at the Department of Health and Human Services during the Ebola crisis.

Notably, there doesn’t appear to be a strong link between how hard countries were hit by COVID-19 and their sense of urgency around it or infectious diseases overall. Adults in Italy and Spain, two early epicenters of the pandemic, were most likely of the surveyed countries to cite COVID-19 as a major threat — but Canadians reported similar levels of concern, despite a significantly lower death toll than either European country.

Separate Morning Consult polling indicates that over the past two months, vaccine hesitancy has fallen by an average of 7 percentage points across 15 countries, and that Russia and the United States have the highest shares of adults who say they don’t plan to get vaccinated.

Public sentiment may instead be tied to the public health messages put out over the past year, as well as how far along a country is in its vaccination campaign, analysts said. Six percent of Canadians are fully vaccinated, compared with about 1 in 5 Italians and Spaniards, according to Johns Hopkins data.

Political ideology also plays a role. In the United States, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to cite COVID-19 and the spread of infectious diseases as major threats to the country.

Even so, adults across countries largely also viewed the spread of infectious diseases in general as a major threat, with that share ranging from 53 percent in Australia to 75 percent in Italy. That indicates the COVID-19 pandemic “struck the consciousness that we should be prepared for an infectious disease,” said Esther Krofah, executive director of the Milken Institute’s FasterCures center.

As policymakers consider how to tackle burgeoning health crises in the future, “the best way to think about this is not a headline-driven approach and response, but rather creating that sustainable infrastructure that, if all works well, people actually don't care about what the potential threats are,” Krofah said.

Momentum for sustained public health investment and better global cooperation is building, with U.S. lawmakers introducing legislation to address gaps exposed by the pandemic and the World Health Organization calling for the creation of an international pandemic treaty. Last week, the Biden administration announced how it will distribute the first 25 million shots of the 80 million it’s pledged to share with other countries, with nearly 19 million doses set aside for Covax, the global vaccine-sharing program.

Yet the political and practical barriers of the COVID-19 pandemic are sure to surface in any future global health crisis. Covax, which was designed to ensure equitable vaccine access across the globe, is dealing with a lack of supply that emerged because wealthier countries like the United States bought up millions of doses while vaccines were still in development last summer.

“My hope is that at the end of this, we'll find a way to be more cooperative,” Ramirez said. “But I'm concerned in the world of realpolitik, if there's another massive disease outbreak, that a lot of that stuff will fall by the wayside. Nobody really knows how the next pandemic plays out.”

Gaby Galvin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade