Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine Brings Varying Political Boosts for Leaders of Western Response

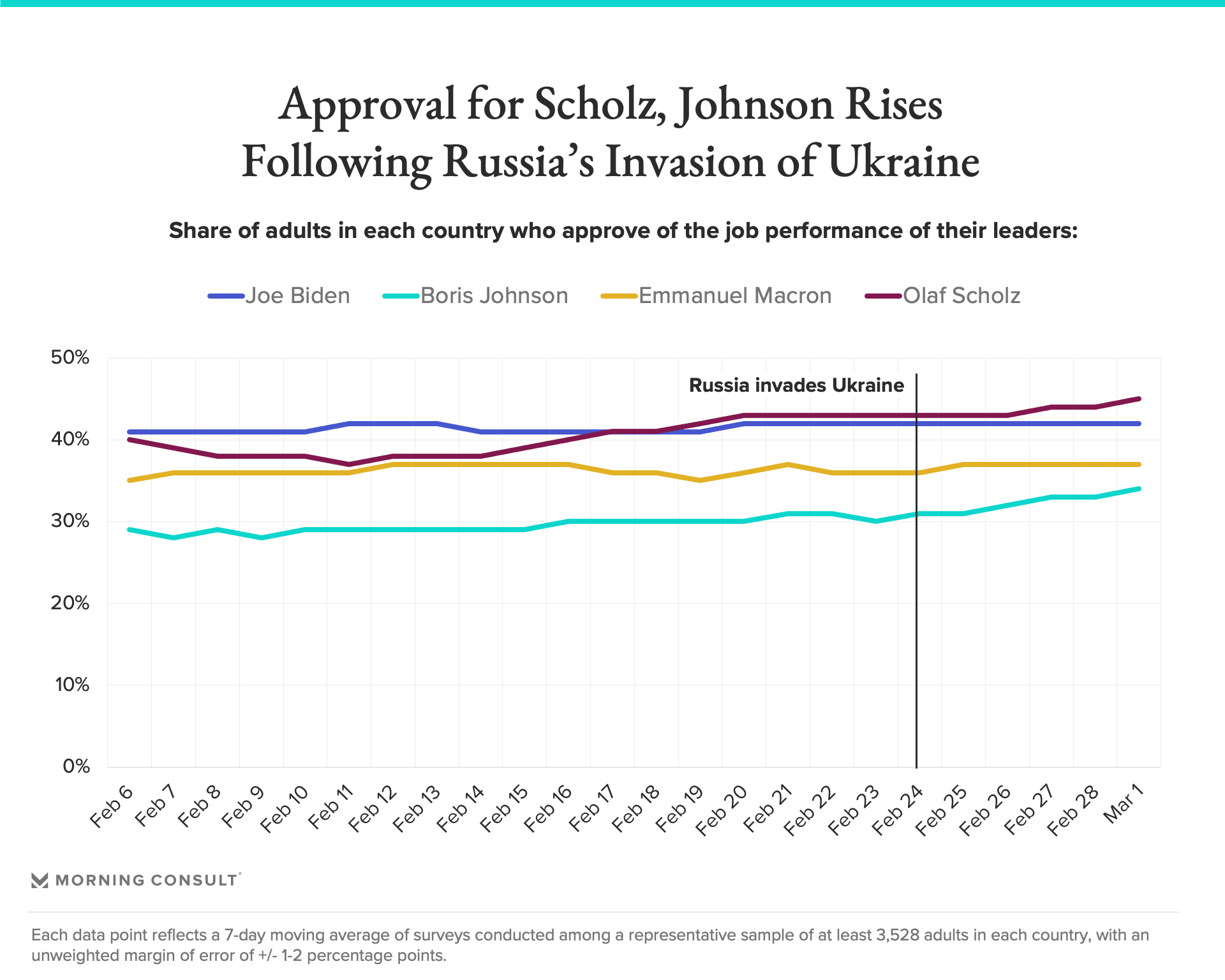

While national leaders on a wartime footing often benefit from a surge of support from a unifying public that faces a common threat, Morning Consult trend data across NATO’s four largest economies shows that only two chief governing executives are seeing upticks in job approval in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

On the numbers

- British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s approval rating has risen 3 percentage points since the Feb. 24 invasion while his German counterpart Chancellor Olaf Scholz has seen a 2-point gain. Those upticks form part of a 5-point bump in backing for each leader since Feb. 6.

- Meanwhile, U.S. President Joe Biden and French President Emmanuel Macron have seen little to no bounce in approval over the past week.

The big picture

While the so-called “rally around the flag” effect has brought increasingly muted returns in the West as its people have become more inclined to partisan division than national unity, there are other reasons to believe these leaders have seen little returns domestically from their actions against Russian President Vladimir Putin — especially the fact that Russian forces aren’t waging war in their own backyards.

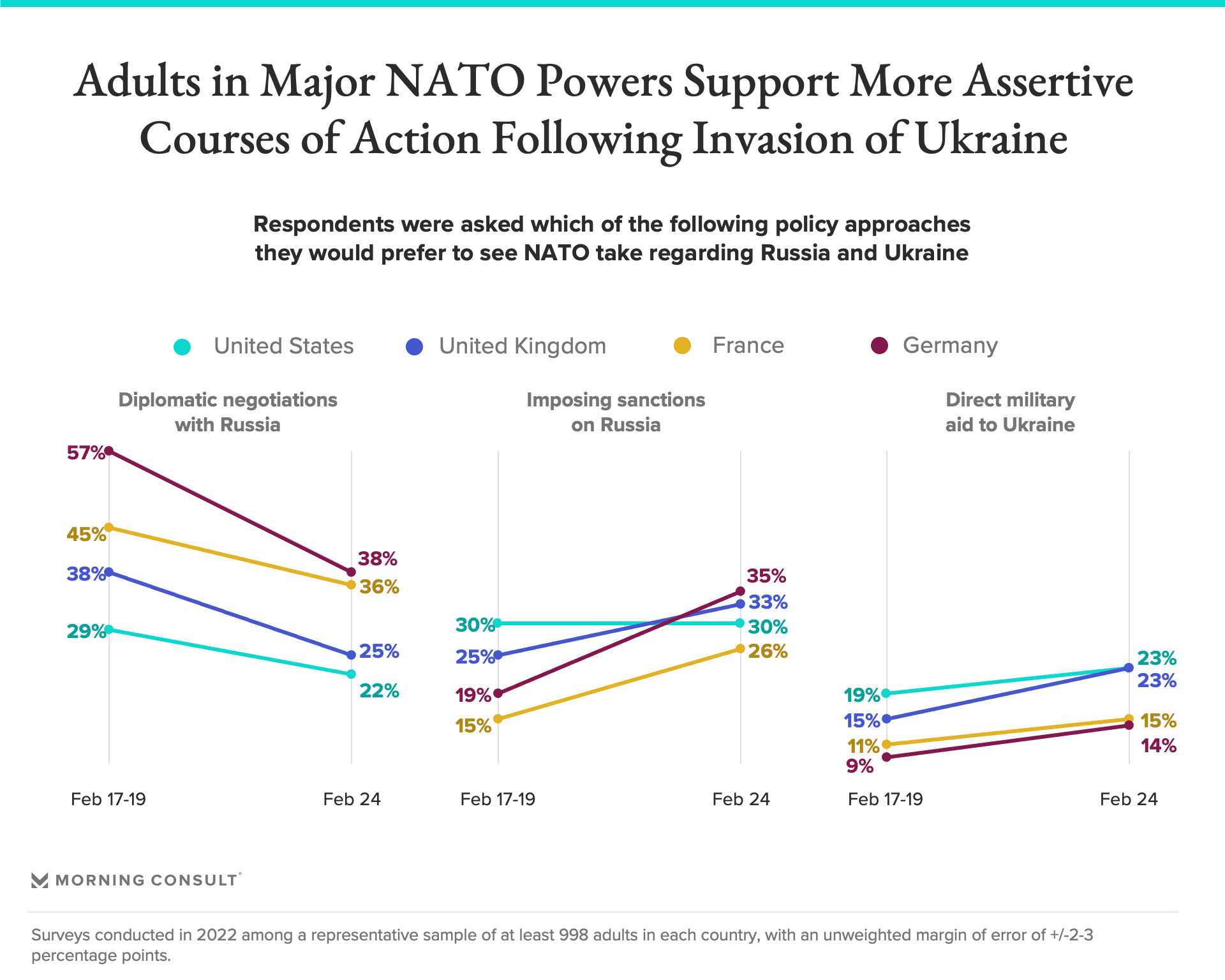

But even though Western populations aren’t falling in line behind their leaders, they have become much more hardened in their views of how NATO should handle Russia’s aggression, with the share of people backing diplomacy over sanctions or direct military aid to Ukraine falling 19 points in Germany, 13 points in the United Kingdom, 9 points in France and 7 points in the United States.

It’s easy to see how the bleak images emerging from the conflict drive sentiment in a bellicose direction. The sanctions imposed by the West have been followed by exits of many multinational brands from the Russian market and a massive shift in the defense policy of Germany, which initially appeared reluctant to punish Russia for its aggression.

In the United Kingdom, the Johnson government, too, has led the charge in sending weapons to Ukraine, which has been a welcome distraction for an embattled prime minister. Some countries are even considering allowing their own citizens to volunteer for combat in Ukraine, and some observers have called for NATO to impose a no-fly zone over Ukraine or even to strike the Russian forces.

It’s a treacherous path to tread, according to Dr. Osamah F. Khalil, the head of international relations at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School. He points out that sanctions are appealing tools for politicians as they require little sacrifice, but also take a long time to show results and are rarely decisive as economies adapt to new realities.

But pumping military equipment into Ukraine could cause the same cycle of escalation and radicalization that played out in Syria 11 years ago, he said.

“As the invasion continues, there will be more bombing, more imagery of refugees, and the pressure on Western capitals to go beyond sanctions is going to increase. The question is, does the pressure increase for diplomacy or for greater amounts of military assistance to Ukraine?” Khalil said.

The latest Morning Consult surveys were conducted Feb. 23-March 1, 2022, among a representative sample of at least 3,528 adults in each country, with an unweighted margin of error of plus or minus 1 to 2 percentage points.

Matthew Kendrick previously worked at Morning Consult as a data reporter covering geopolitics and foreign affairs.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade