Hispanic Adults Use WhatsApp More Than the General Public. Disinformation Campaigns Are Targeting That Vulnerability

Key Takeaways

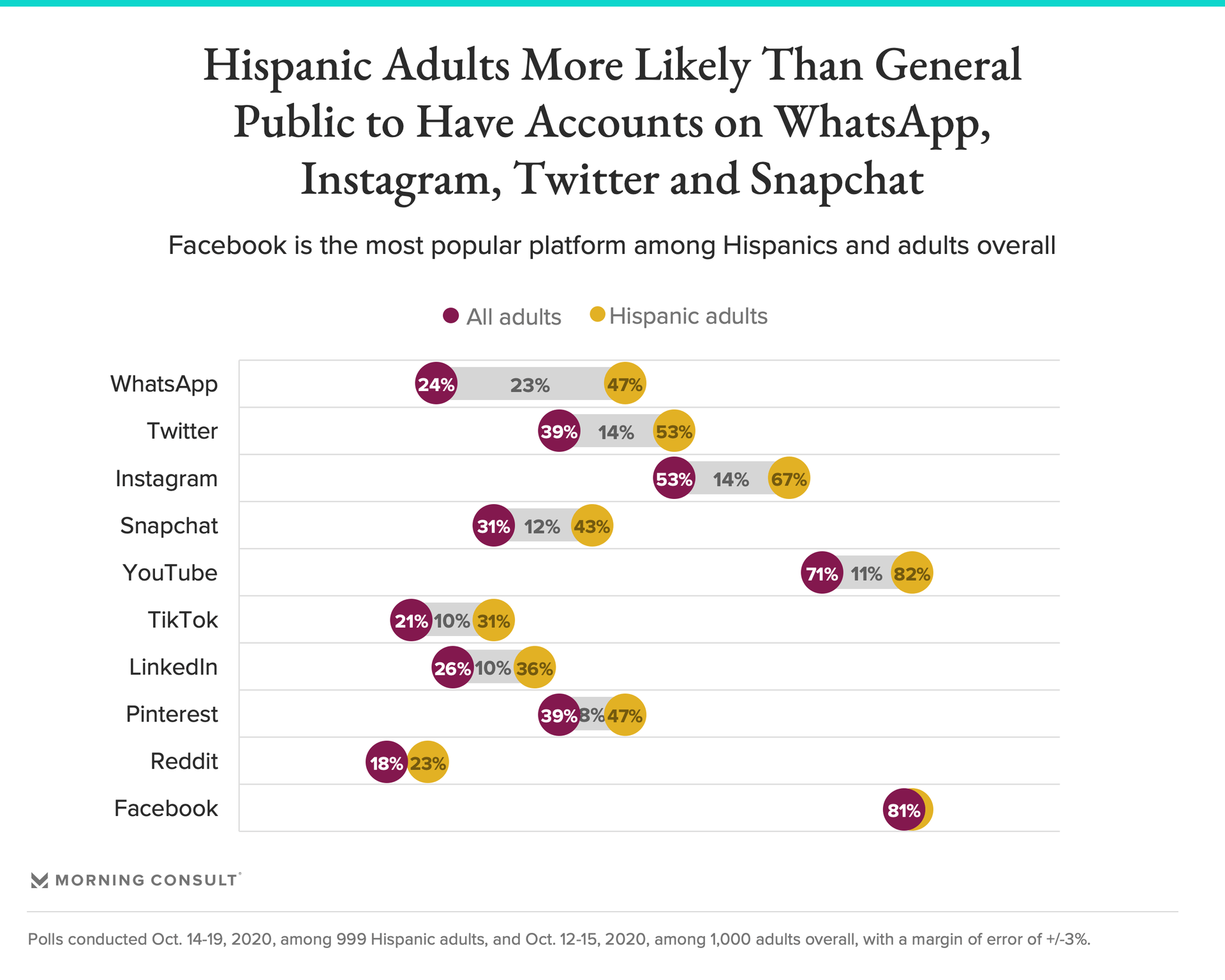

Hispanic adults are more likely to have accounts on WhatsApp, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube than adults overall.

47% of Hispanic adults are on WhatsApp -- 23 points higher than the general public.

But little difference exists on perceptions of the amount of misinformation online: 35% of Hispanics said they see misleading information “often,” compared to 31% of adults.

The data in this article is drawn from a poll of 999 Hispanic adults, gauging attitudes on a variety of social, political and economic issues.

With Latinos expected to make up 13.3 percent of all eligible voters in the upcoming U.S. elections, candidates and political action committees aren’t the only ones trying to sway their votes. Disinformation agents are getting in on the persuasion campaigns, too.

And as the coronavirus pandemic forces more people to turn online to discuss politics, disinformation researchers studying campaigns targeting Latino voters -- projected to surpass Black voters as the largest voting minority bloc this year -- are worried the community has become a sitting duck for bad actors looking to cause confusion online about the voting process and candidates’ platforms.

New Morning Consult polling sheds light on just how easy it has been for the voting base to become the targets of both the intentional and unintentional spread of false information on social media -- especially on WhatsApp, where encrypted messaging and private group chats, akin to text messages and email, have typically made it hard to monitor for such information.

Nearly half (47 percent) of the respondents in Morning Consult’s Oct. 14-19 survey of 999 Hispanic adults said they have a WhatsApp account, compared to 24 percent of adults overall who said the same thing in a separate survey conducted Oct. 12-15. And 56 percent of those 474 Hispanic WhatsApp users said they turn to social media daily as their source for news -- 10 percentage points higher than Hispanic adults overall.

Compared to adults overall, Hispanic respondents were also more likely to say they had accounts on a variety of social media platforms, including YouTube, Instagram, Twitter and TikTok.

“When you have an electorate that in many ways is up for grabs, and now you have most of them all consuming content in one place, that's your perfect storm,” said Lizette Escobedo, director of the National Census Program at NALEO Educational Fund, a nonprofit that promotes Latino civic engagement.

The two surveys have a margin of error of 3 percentage points and were conducted in English and Spanish. The subsamples of Hispanic and all adult WhatsApp users have margins of error of 5 and 6 points, respectively. Of the 999 Hispanic adults who responded, 47 percent identified as Mexican, 18 percent as Puerto Rican, 8 percent as Cuban and the rest as other Central and South American ethnicities or another ethnicity.

With the 2020 presidential election expected to come down to razor-thin margins in a handful of swing states, disinformation campaigns have been targeting Latino voters in droves throughout the election cycle, said Jacobo Licona, a disinformation researcher for EquisLabs, a research group that focuses on educating and mobilizing Latino voters.

Some campaigns focus on sharing false information about the voting process, such as giving the wrong day and time, while others focus on misleading information about politicians’ platforms. A popular go-to, Licona said, is to instill fear that Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden will bring a socialist government reminiscent of the regimes in Cuba and Venezuela, even though Biden does not identify himself as a socialist.

Many of the campaigns targeting Latino voters take the form of the typical disinformation campaign, with various pages and accounts across platforms coordinating which memes or videos to share. Licona noted a network of conservative-leaning Latino Facebook pages that have been linking their disinformation campaigns together, with pages reaching “tens of thousands” of followers, and also said that there are some notable Latino far-right influencers who are also promoting these narratives.

Engagement on the coordinated posts also tends to be a mix of organic, natural user reactions and “suspicious” reactions from bots or other disingenuous actors, so it can be hard to know how harmful the posts actually are, he said.

And while social media platforms have been cracking down on the influence of both misinformation and disinformation, researchers are left filling the gaps -- especially when it comes to moderating Spanish-language false information.

“I’m seeing this happening everywhere,” Licona said. “Oftentimes, it’s misinformation -- people not even knowing that what they’re spreading” is false.

Escobedo said that much of the misinformation sharing is taking place behind the private chats and encrypted messages on WhatsApp, which is more challenging for researchers to track and debunk. And she said most of the conversations that take place on WhatsApp are between Latino immigrants and their families or loved ones who live abroad, so much of the misinformation that spreads on the platform comes from individuals users already know and trust.

“It is a new frontier for us and for a lot of organizations trying to figure out how do you flag disinformation and misinformation that might flow through” WhatsApp, she said, adding that the app’s research difficulties are similar to trying to track misinformation spreading on NextDoor, where users need to verify that they live in the neighborhood they’re trying to join.

WhatsApp pointed to a page on its website detailing its election misinformation strategy, which includes limits on forwarded messages and a partnership with the International Fact-Checking Network so users can directly message fact checkers on the app. WhatsApp also said its platform is more akin to email or text messaging than to general social media sites, so most messages are sent on a one-on-one basis instead of being shared with a mass of followers.

Another part of the problem is just how organically misinformation spreads among users, researchers say, making it more difficult to be detected by the average person. In the survey, there was little difference between Hispanic adults and adults overall regarding how much false or misleading content they said they have been exposed to: 35 percent of Hispanic adults said they see misleading information “often” on social media platforms, compared to 31 percent of adults overall.

Both groups were inclined to express misgivings on the ability of social media platforms to moderate election-related information, with 36 percent of Hispanic adults saying platforms were doing a poor job, compared with 33 percent of all adults who said the same. Similar shares also said the platforms were doing a fair job, including 35 percent of Hispanic adults and 39 percent of adults overall.

However, Latino voters are still concerned about misinformation, even if they might not be aware of how much they’ve encountered. In NALEO’s latest weekly survey of 400 registered Latino voters released Tuesday, 77 percent said they were concerned that their friends or family members would be sent misleading videos about the presidential candidates on social media.

Meghna Mahadevan, chief disinformation defense strategist at progressive youth-led immigrant network United We Dream, said many of the Latino users they engage with in their fact-checking efforts have expressed concerns about family and friends falling into the disinformation rabbit hole. United We Dream has launched groups on WhatsApp where they answer questions and debunk common misconceptions about the voting process and other issues related to the elections.

But advocacy groups can’t do this work alone, and Mahadevan said social media companies need to dedicate more resources to Spanish-language fact-checking, more safeguards for creating accounts and strengthened security to combat the plethora of Latino-targeting disinformation circulating online.

“This point that we're at in 2020, with this election and the way that it really snowballed, has been inevitable,” Mahadevan said. “With the way the social media algorithm grows and gains information, it will kind of continue to spiral until we find ways to get platform accountability.”

Sam Sabin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering tech.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade