Energy

Hydrogen Cars Aren't the Hindenburg, and Other Marketing Hurdles for Toyota's Mirai

At the Washington Auto Show in January, Toyota Motor Corp. representatives spent much of their time explaining to curious spectators at the Toyota Mirai display what the hydrogen fuel cell vehicle does not do: No, the car does not run on water; it emits water. No, you do not have to charge it like an electric vehicle.

“What do they do if somebody hits you?” asked Jose Banzon, 56, from Centreville, Va. “Do you blow up like the Hindenburg?”

For a company that is “bullish on fuel cells,” as Tom Stricker, vice president of product regulatory affairs for Toyota in North America, said at the auto show, Banzon’s remark is representative of just one of the hurdles Toyota faces as it makes a huge push to expand Mirai sales outside of California -- the only U.S. state that has retail hydrogen fueling stations. (To answer Banzon’s question: No, it won’t explode, Toyota says, as the valves on the fuel cells are designed to shut down and vent off hydrogen safely during collisions.)

The company that launched the hybrid Prius in 1997 is betting on its hydrogen fuel cell technology to further position itself as a clean-energy leader. Like it did with the Prius, Toyota is hoping to use the Mirai, one of the first mass-produced hydrogen fuel cell cars when it began selling in Japan in 2014, as a way to become the dominant player in a nascent market.

But without government help, either in the form of regular incentives for buyers or long-term commitments to invest in fueling station infrastructure, Toyota is likely to find it difficult to market the vehicle to consumers who don’t understand the technology and to convince skeptics that it’s a viable business venture.

The Prius, which went on sale in Japan in 1997 and in the United States in 2000, also had its share of naysayers initially, said Ed Lewis, policy communications director for Toyota in North America, in a February phone interview. Yet Toyota leveraged its first-mover status to become a leader in hybrids, last year selling 1.52 million units globally, an 8 percent rise from 2016.

Government incentives, such as a federal tax credit of up to $3,400 for new hybrid vehicle buyers in 2005, were key to elevating the Prius, Lewis said. (The tax credit expired at the end of 2010; however, there are still other federal incentives available for energy-efficient cars.)

“The government understood the importance of the technology and its potential,” he said. “They had to stoke the market. It wasn’t an overnight success; it took us a while.”

The Prius also benefited from high-profile early adopters, such as actor Leonardo DiCaprio, said Chris Santucci, energy and environmental research program manager for Toyota in North America.

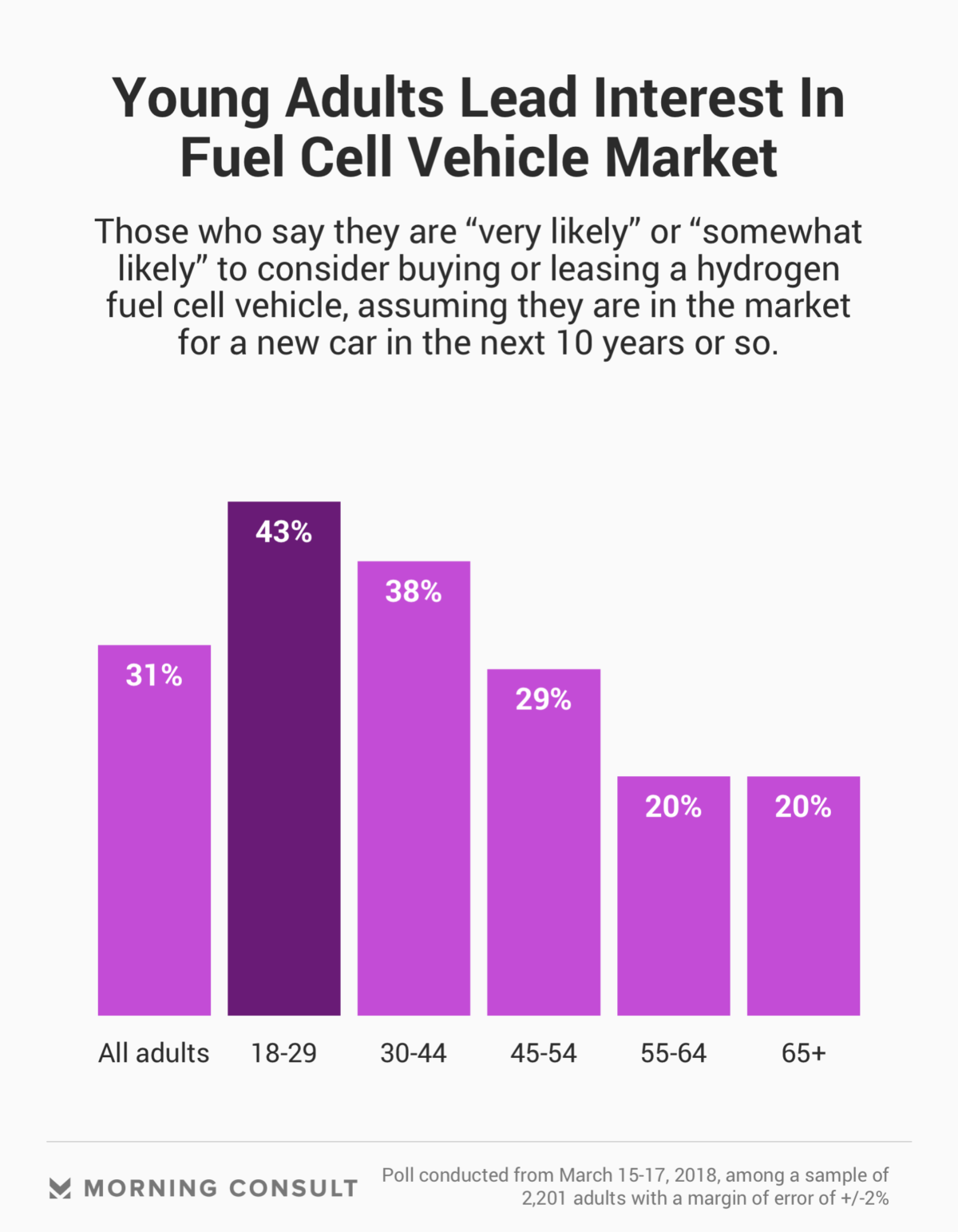

A Morning Consult survey shows Toyota has a long way to go to raise the profile of the Mirai, which debuted in the United States in 2015. In a poll of 2,201 people conducted March 15-17, 58 percent said they haven’t heard anything about the car, compared to 21 percent who had heard “not too much” about it and 21 percent who had heard “some” or “a lot.” The poll’s margin of error is 2 percentage points.

Lewis declined to disclose the Mirai’s marketing budget, but Santucci said Toyota is hoping to increase recognition through outreach with think tanks, thought leaders and politicians. The model is also making the rounds at auto shows, including the New York International Auto Show, which runs Friday to April 8.

So far, Toyota has sold about 5,300 units of the Mirai in Japan, North America and Europe, according to Santucci, with more than 3,000 of those units sold in California. Other automakers offer a fuel cell model, but Toyota accounted for over 77 percent of global sales of such cars in 2017, according to a March report by Information Trends, a market research firm in Washington.

The goal for Toyota is to produce 30,000 fuel cell vehicles globally beginning in 2020, Santucci said.

In California, alternative-fuel vehicles have a champion in Gov. Jerry Brown, who in January announced a $2.5 billion initiative that includes increasing hydrogen fueling stations to 200 by 2025. The stations, financed by the state government, Toyota, Honda and other automakers, cost $1 million to $3 million each, according to Santucci. The state also has incentives for fuel cell car buyers, including a $5,000 rebate.

Outside of California, the National Conference of State Legislatures is “not seeing a ton of action” on fuel cell vehicle incentives compared to those for electric vehicles, said Kristy Hartman, NCSL energy program manager. But she said the Mirai is more likely to find a market in Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island and Vermont, which, along with California, in 2013 committed to having at least 3.3 million zero-emission vehicles on their roadways by 2025.

There’s at the very least “an appetite for clean and renewable energy" among federal lawmakers, said Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.), a member of the Senate Fuel Cell and Hydrogen Energy Caucus, in a Capitol Hill interview in February before the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 was signed into law Feb. 9. The law has a provision that retroactively extended through Dec. 31, 2017, a $4,000-to-$40,000 tax credit for alternative fuel vehicles purchases.

But this kind of year-to-year uncertainty regarding incentives leaves fuel cell vehicles at a disadvantage compared to battery electric vehicles.

Toyota is offering its own incentives for the Mirai, which retails for $58,365, in the form of three years' or $15,000 worth of fuel, whichever comes first.

One of the Mirai’s selling points is that it takes three to five minutes to refuel the car, which can run for up to 312 miles per tank, compared to the more than five hours to charge Toyota’s Prius Prime at home and two hours at a public charging station. Yet it’s an advantage unavailable outside of California, home to all 32 U.S. retail hydrogen fueling stations.

Air Liquide SA, a French producer of industrial gases, is working with Toyota to set up 12 hydrogen fueling stations in the Northeast. Cassandra Franceschini, Air Liquide’s marketing and communications manager, said so far it has operational stations in Providence, R.I.; Hartford, Conn.; Mansfield, Mass.; and Hempstead, N.Y., but they will not open until the third or fourth quarter of 2018 due to the time needed to educate local officials and safety departments about the technology.

Federal support for a wider rollout of hydrogen stations appears unlikely, given that the Trump administration’s infrastructure plan, released Feb. 12, lacks provisions for hydrogen infrastructure.

Until the infrastructure is in place, for most people, even those who have the budget for one, a hydrogen car is “not going to be on their radar,” said Elgie Bright, chair of the automotive marketing program at Northwood University in Midland, Mich., in a Feb. 6 phone interview.

He said Toyota should focus on marketing the Mirai in areas where gas prices are generally higher; however, because national gas prices are currently under $3 a gallon, he said hydrogen cars’ appeal to consumers is likely to be limited.

Anna Gronewold previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering finance.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade