From Name, Image and Likeness to Pay for Play, Americans Increasingly Support Compensation for College Athletes

Key Takeaways

42% of U.S. adults believe schools should pay players, compared with 36% who oppose such a model.

56% of U.S. adults say college athletes should be compensated equally, regardless of which sport they play or how much revenue that sport generates.

After years of bureaucratic delays, Division I college athletes across the United States will have the opportunity to earn money based on the commercial use of their name, image and likeness beginning Thursday under temporary guidance expected to be passed by the NCAA tomorrow. New research shows that this move toward greater economic freedom for college athletes is largely popular among the general public.

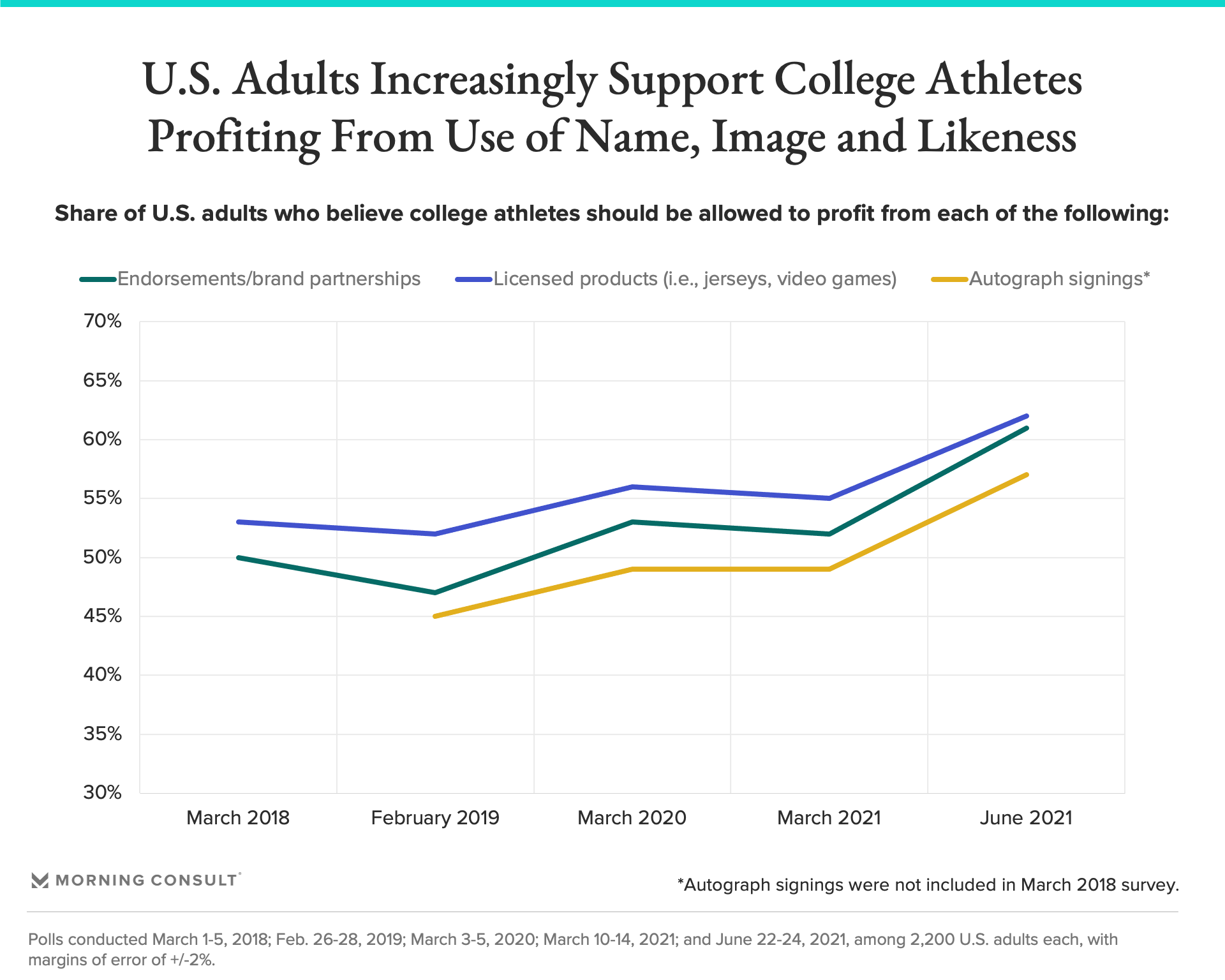

In a Morning Consult poll conducted June 22-24, the share of U.S. adults who believe that college athletes should be allowed to profit from the use of their name, image and likeness was nearly three times greater than the share who opposed such rights for athletes. Support for athletes being allowed to monetize their identity has also increased since earlier this year.

Sixty-one percent of respondents supported allowing student-athletes to make money by endorsing products and services or partnering with brands (up from 52 percent in a March 10-14 survey), while just 22 percent said athletes should not be allowed to do so. Similarly, 62 percent of adults said athletes should be allowed to cash in on the use of their identity in licensed products like jerseys or video games (up from 55 percent in March), which just 20 percent of adults opposed. Allowing athletes to earn money in exchange for autographs was slightly less popular, with 57 percent in favor (up from 49 percent in March) and 25 percent opposed.

The NCAA Division I Council’s recommendation to temporarily waive its rules prohibiting athletes from profiting from their name, image and likeness follows last week’s ruling by the Supreme Court against the NCAA in the Alston antitrust case, which raised questions about the legality of the NCAA’s restriction of athletes’ compensation. The association had hoped Congress would pass a national bill establishing a set of uniform national rules governing such activity, but that won’t happen before at least eight separate state laws governing name, image and likeness take effect Thursday.

During hearings this month, Republicans on the Senate Commerce Committee were seemingly more eager to pass a law in the short term aimed at allowing athletes to benefit from their name, image and likeness, while Democrats wanted a more comprehensive college athletics reform bill that included scholarship protection and health care.

Democratic respondents were more likely to back the name, image and likeness movement than Republicans. Sixty-nine percent of Democrats approved of athletes being paid for brand partnerships, compared with 52 percent of Republicans, according to the most recent poll. Similarly, the share of Democrats supportive of athletes being paid for the use of their license (71 percent) was larger than the share of Republicans with the same opinion (52 percent).

While the NCAA has reluctantly agreed to overhaul its prohibitions on athletes making money for marketing deals, it continues to beat back calls for member schools to pay athletes salaries to play sports. The public, however, has also been moving in the direction of supporting a model under which athletes receive monetary compensation from schools.

In last week’s survey, 42 percent of U.S. adults said universities should pay their student-athletes, while 36 percent opposed schools paying athletes. The share of adults who support athletes being paid has increased by 10 percentage points since March 2020, including a 6-point gain over the past few months.

Black adults, who make up a significant share of athletes in revenue-generating college sports such as football and college basketball, were highly supportive of a pay-for-play model, with 68 percent in favor and 17 percent opposed. By comparison, 38 percent of white adults supported paying athletes, while 40 percent opposed it.

Creating rules to pay college athletes raises difficult issues, particularly when men's sports programs often generate more revenue than women's programs, as evidenced by the survey.

Sixty-five percent of respondents said female athletes should be compensated the same as men who play the same sport, while 56 percent agreed that athletes in different sports should be compensated the same, regardless of how much money that sport brings into the school. In addition, respondents were roughly divided over the notion that a school should pay star players, who generate more money for the university than others, larger salaries than their peers: 41 percent disagreed and 38 percent agreed.

The opening of the name, image and likeness era this week represents one of the most significant breakthroughs in college sports history, but it’s more likely a first step in the advancement of economic rights for college athletes than a final frontier.

Alex Silverman previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering the business of sports.