Energy

North Dakota, in Last Place for Solar, Takes Steps to Move Up the Ranks

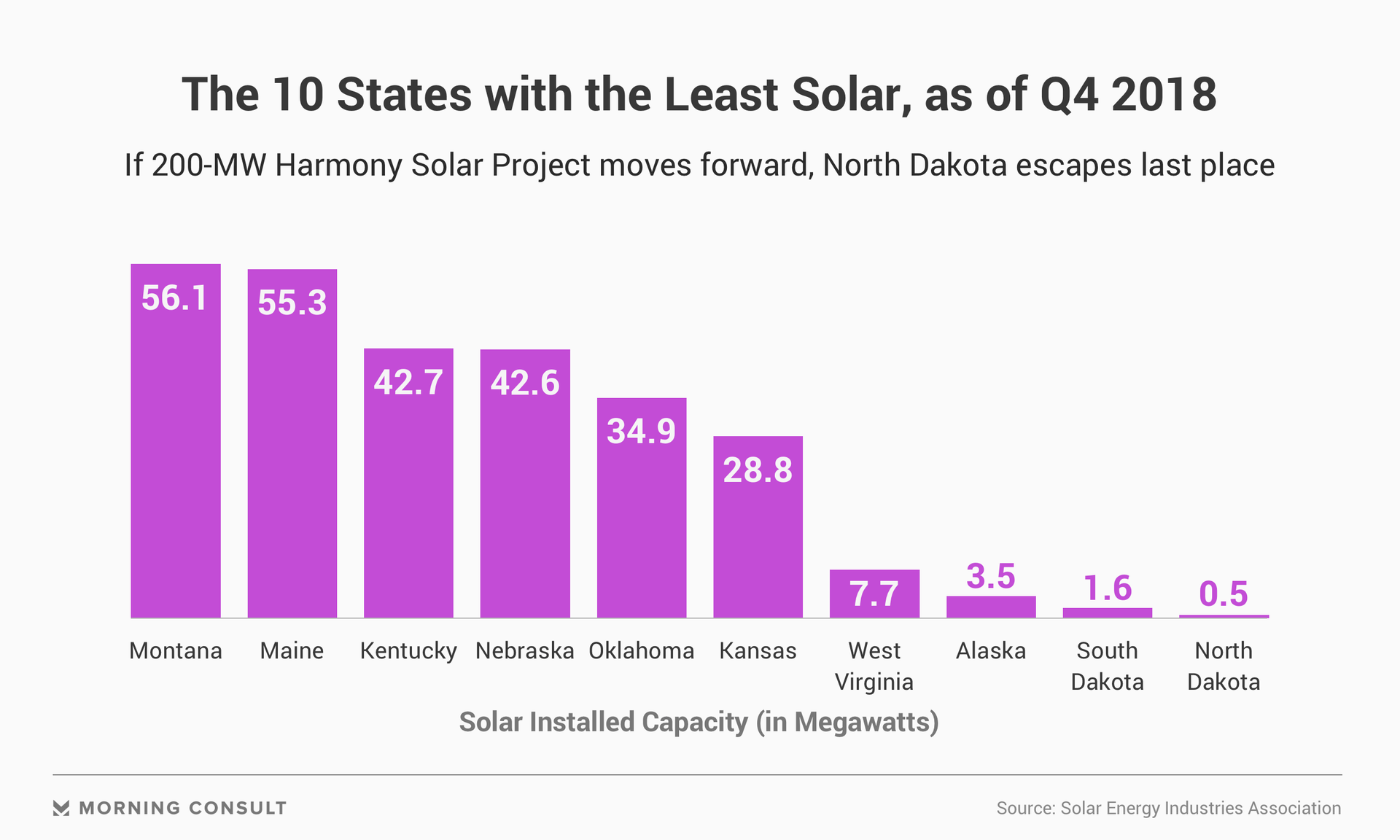

Solar energy has been slow to enter the scene in North Dakota, due in part to its lush farming soil, plentiful fossil fuel resources and strong wind suitable for turbines. As of the end of last year, North Dakota ranked last in solar installed capacity among all 50 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico.

But the state approved its first commercial solar project in February. And at the same time that the economics of solar grow more attractive to developers, the discussion surrounding the commercial project led to an attempt at a regulatory change that could ease the approval process for future large-scale solar endeavors on the state’s key farmland.

North Dakota had less than 0.5 megawatts of solar capacity installed as of the end of 2018, according to data from the Solar Energy Industries Association and Wood Mackenzie Ltd.

Before Edina, Minn.-based Geronimo Energy LLC proposed its 200-MW Harmony Solar Project near Fargo, “nobody had put forth a project for consideration by the commission in terms of siting approval,” said Brian Kroshus (R), chairman of the North Dakota Public Service Commission, who voted in favor of the project in a 2-1 split vote.

The approval “sends a positive message to the investment community” that North Dakota is receptive to this type of development, he said.

There appear to be myriad reasons for solar’s slow pickup in North Dakota, but an aversion to renewables is not one of them: Though lagging on solar, the state ranks 10th in the country for wind installed capacity at 3,155 MW -- over a fourth of the state’s net energy production -- with an additional 256 MW of wind capacity projects currently under construction. Geronimo has already developed the Courtenay Wind Farm in North Dakota that is owned and operated by Xcel Energy Inc., which is based in Minneapolis.

Unlike solar, which has a larger land footprint, wind projects allow producers to farm in the area surrounding a turbine -- something “important in an agricultural state like North Dakota,” said a spokeswoman for Sen. John Hoeven (R-N.D.) in an email.

Solar as an energy resource is not often discussed at the state Capitol and “is usually dismissed as a viable energy source given our northern location and climate,” State Rep. Corey Mock (D), ranking member of the Appropriations Committee’s Government Operations section and former ranking member of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee, said in an email.

“As long as wind, coal, oil, and gas remain relatively inexpensive, and as a net energy exporter with grid limitations, solar is destined to trail far behind the rest of our state’s energy sources for the foreseeable future,” Mock said.

But when it comes to the state’s government, energy development “is largely nonpartisan,” said Mock, and an “all-of-the-above” energy strategy generally prevails.

“It’s hard to say if this is a one-off project or the start of a new trend, but if other solar projects come forward, they’ll likely mirror the path of the Geronimo proposal,” including garnering support from landowners and the community, said Mock.

To some extent, concerns over the climate’s impact on solar are valid, said Myles Burnsed, vice president of new markets for EDF Renewables Inc., a renewable energy company based in San Diego. In cloudier or snowier areas, “the cost for the project is the same, but it produces less energy because there’s less sun,” and “it takes longer to pay off the project.”

But Lindsay Smith, Geronimo’s director of marketing and communications, said by email that as technological advancements have reduced solar costs, large-scale solar is now competitive in most of the United States, “including the Upper Midwest,” she said.

“This is why many states are seeing the first large-scale solar projects being proposed or constructed in their states,” said Smith.

In a separate email, she said the company is “actively marketing” the Harmony project and working to secure power purchase agreements, with an intended operational date for the project in late 2020 or in 2021.

The process to determine whether to approve the Harmony project launched a discussion over a 1970s-era state regulation that deems prime farmland, or areas particularly fertile for agriculture, to be exclusion areas, which are restricted from certain uses under state law.

The state’s PSC subsequently moved on March 27 to remove prime farmland from the definition of exclusion area. But the change must undergo review by the state attorney general’s office, then the commission must notify the state’s Legislative Council. Subsequently, the state’s Administrative Rules Committee has the opportunity to deny it.

“The concerns that we had about feeding the world in the ’70s, you don’t hear as much talk about that anymore,” said Randy Christmann (R), the dissenting vote on the Harmony project because he believed the rule should have been changed before the project’s approval.

Kroshus has maintained that the Harmony project was an issue of private property rights. The landowners and adjacent landowners supported the solar project, and applying the prime farmland rule to Geronimo would have been trying to protect landowners from themselves, he said.

In the past, the commission has approved pipelines, for example, that would cross one or two acres of prime farmland, but the Harmony project is much larger at 1,600 acres and is to be sited on rich soil. The prime farmland rule wasn’t an issue until Geronimo’s project, said Kroshus.

Christmann said the commission hopes that the attorney general completes its review in time for the Administrative Rules Committee’s next meeting in June, and if so, that the rule would likely take effect July 1. It would be surprising if the committee denied the rule change, he said.

As for the prospects for solar energy in the state, Kroshus said he suspects that more solar projects have not been proposed in North Dakota due in part to the state’s lack of a renewable energy mandate through a Renewable Portfolio Standard, which means North Dakota’s utilities are not incentivized to build solar. While investor-owned utilities Xcel Energy and Fergus Falls, Minn.-based Otter Tail Corp., which service North Dakota as well as other states, must meet a clean energy mandate in Minnesota, the companies get to decide where to meet their solar targets.

Dan Whitten, vice president of public affairs with SEIA, said there is a lot of potential for solar development in North Dakota, pointing to its expanse of land and the ability to build solar near population centers there. But he said solar companies are likely inclined to look at development opportunities in states with an RPS, unlike North Dakota.

Brian Draxten, manager of resource planning for Otter Tail, said “the regulatory philosophy” between Minnesota and North Dakota is different, with Minnesota requiring that the cost of externalities be brought down.

“We have nothing against building solar in North Dakota,” said Draxten, adding that the company is focused on opting for the lowest-cost projects. Otter Tail has spoken with Geronimo about whether to purchase power from the Harmony project, he said.

Randy Fordice, a spokesman for Xcel Energy, said in an email that the company does not have any solar projects planned for North Dakota.

Jacqueline Toth previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering energy and climate change.