Nearly Half the Public Wants the U.S. to Maintain Its Space Dominance. Appetite for Space Exploration Is a Different Story

Key Takeaways

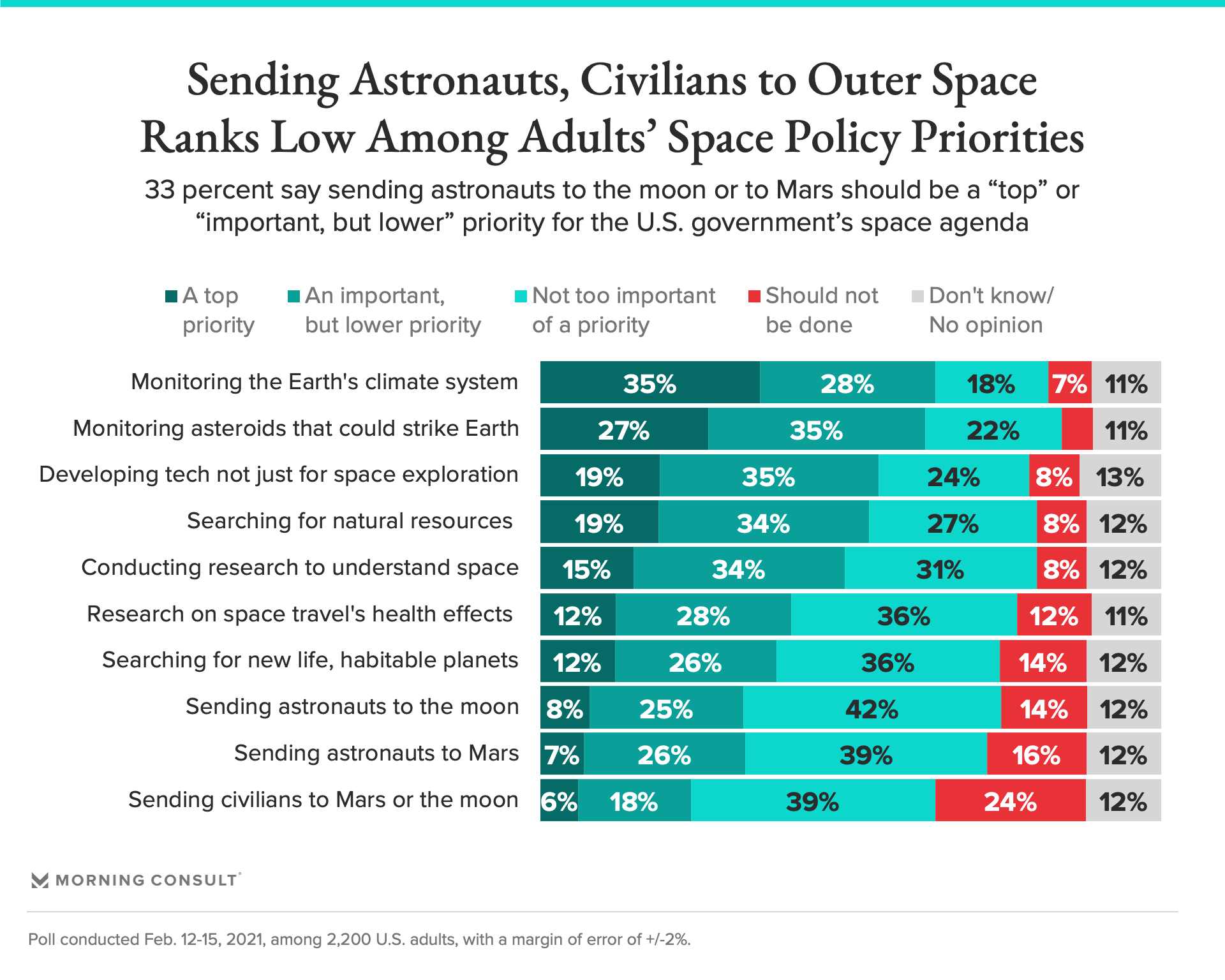

1 in 3 adults said sending human astronauts to the moon or Mars should be a priority, about 30 points lower than the highest-ranked space research priorities.

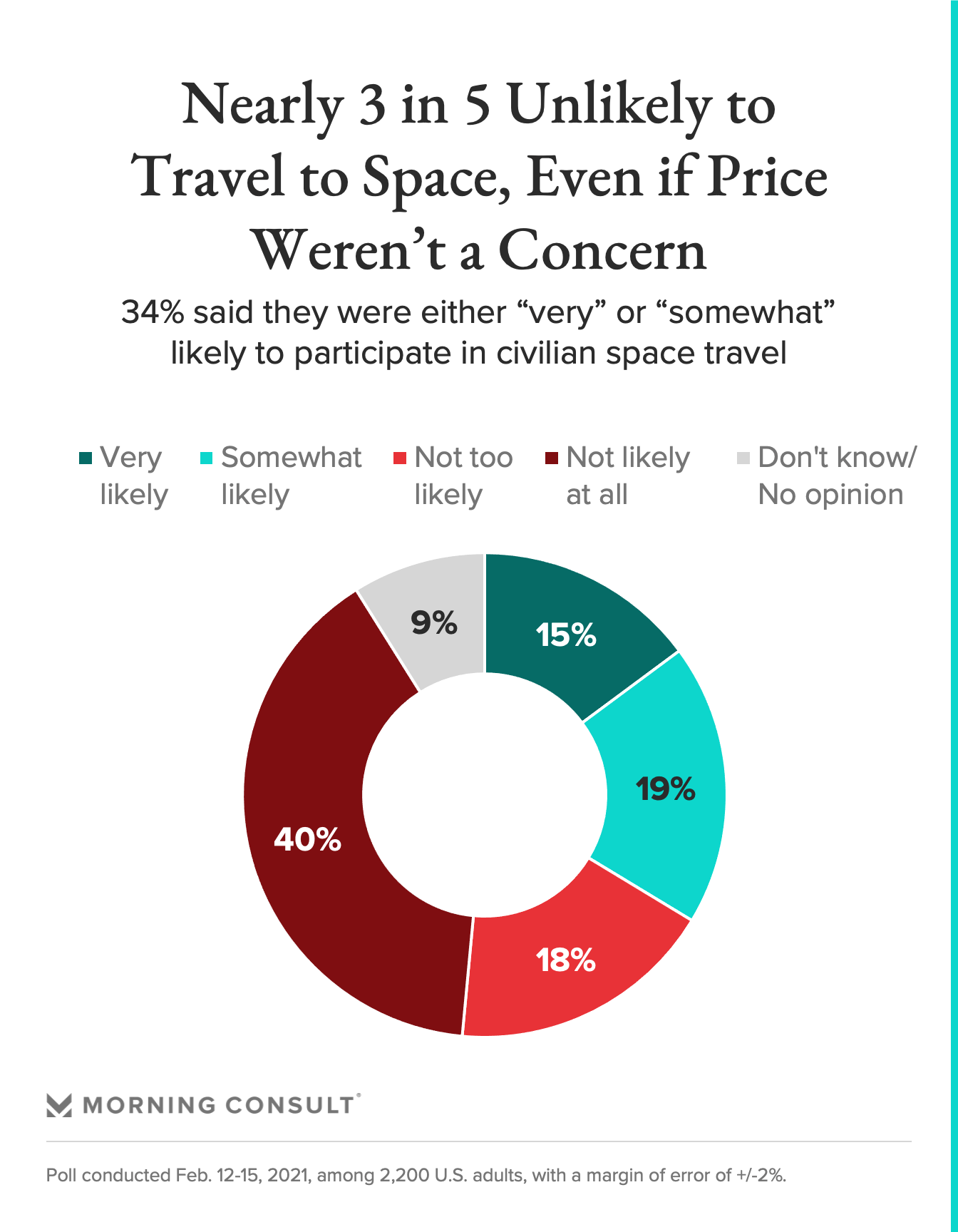

58% said they were either “not too likely” or “not likely at all” to participate in civilian space travel, even if price weren’t a concern, up 10 points from the 48% who said the same in September 2017.

Last week, NASA accomplished a goal that reminded Americans that the future is coming fast: It landed another rover on Mars. Among billionaires and space enthusiasts, that’s just the tip of the iceberg, with many of them believing the United States could send humans outside of Earth’s orbit again in the next 10 years if the country plays its cards right.

But outside of some government agencies or private companies that are setting their sights beyond Earth, the enthusiasm for space travel is much more grounded: Most U.S. adults don’t see sending humans -- no matter if they’re astronauts or civilians -- to the moon or Mars as a high space priority, new polling data suggests. Despite this, much of the public does want the United States to maintain its global dominance in the area.

In a Morning Consult survey conducted Feb. 12-15 among 2,200 U.S. adults, 33 percent said sending human astronauts to the moon or Mars should be a “top” or “important but lower” priority for the U.S. government’s space efforts -- about 30 percentage points lower than monitoring key parts of the Earth’s climate system (63 percent) or monitoring asteroids and other objects that could strike the Earth’s surface (62 percent).

Those priorities shed light on a larger trend among adults’ sentiments on space research and exploration: While a plurality (47 percent) say it’s essential that the United States continues to be a world leader in space exploration, few think it should be a high priority for the Biden administration -- and even fewer say they’d want to embark in space travel themselves, even if price weren’t a concern.

“People have kind of generalized that, ‘Yeah, it's a good thing to do,’ but most people don't spend a lot of time thinking about it,” said John Logsdon, the founder and former director of George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute.

The survey has a margin of error of 2 percentage points.

Investing in space research and exploration ranked 25th on a list of 26 priorities for the Biden administration that were included in the survey. Forty percent said the Biden administration should make it a “top” or “important, but lower” priority, compared with 84 percent who said the same about controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the United States and 81 percent on stimulating the economy to recover from the pandemic.

Yet the public still believes that the United States needs to keep its competitive edge in space to win out against other threats. Roughly half of adults (52 percent) said China is a “major threat” to the United States’ leadership in space research, compared with 45 percent who said the same about Russia and 34 percent about North Korea. Thirty-percent also said they viewed Iran as a “major threat.” Each country surveyed was included based on an assessment by the Defense Intelligence Agency as to who poses a threat to security in space.

When it comes to the specifics of oversight for space-related issues, though, adults were either split or at a loss. For example, when asked which agency or company is best prepared to handle sending human astronauts to the moon, adults were evenly split around 25 percent between federal space agencies, international space partnerships and having no opinion; about 1 in 5 respondents pointed to private aerospace companies.

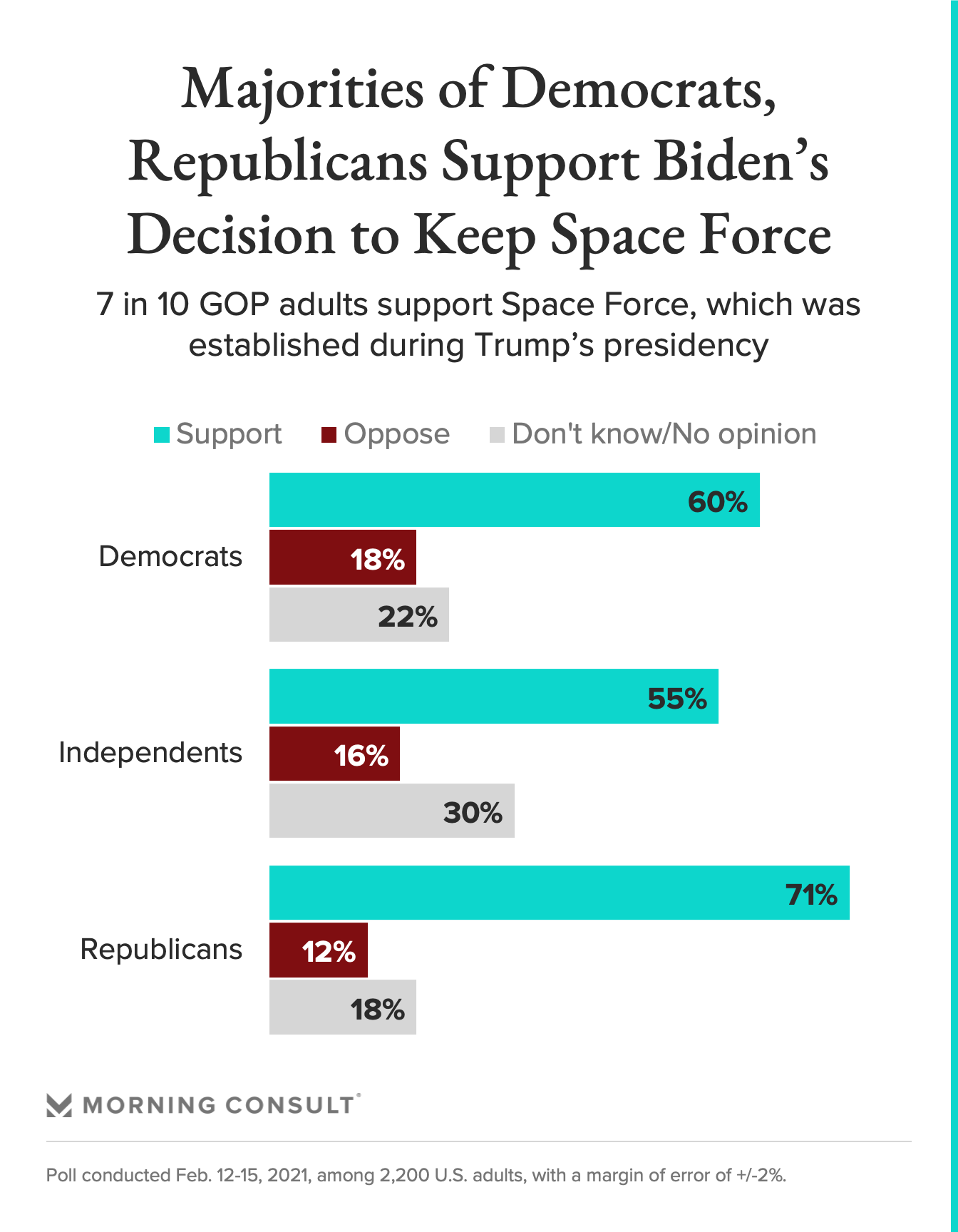

While most people said they supported Biden’s decision to keep Space Force (61 percent), the new branch of the U.S. Armed Forces established under the Trump administration, more people said they weren’t sure or had no opinion (23 percent) about the move than those who opposed it (15 percent). And nearly identical shares of people said Space Force should remain a military agency (33 percent) or they didn’t know or had no opinion (30 percent), indicating that much of the public might not be as up to speed on the government’s space efforts.

But Logsdon said space research doesn’t need to be a top priority for the United States to keep its competitive edge. By his estimates, NASA’s annual budget makes up “less than one-half of 1 percent” of the U.S. government’s budget. And Congress fell just short of completely funding NASA’s $25.2 billion budget request last year so it could keep an anticipated 2024 moon-landing project on schedule by instead awarding the agency with about $23.3 billion.

“To get that amount of money, you don’t have to be a top priority,” he said.

While Logsdon says it’s too early to tell if the new Congress will fill the gaps left behind in the latest funding bill, the Biden administration is in the early stages of piecing together its space policies.

Earlier this month, White House press secretary Jen Psaki said the administration plans to carry on with the Artemis program, a NASA-led effort in partnership with private aerospace companies to send one man and one woman to the moon by 2024 -- although that timeline is being reassessed.

While Space Force lives on under Biden, questions remain about whether the administration will reinstate the National Space Council, an executive branch group overseeing space policy led by the vice president and including several cabinet secretaries and agency heads.

In the background of these government efforts is the ever-growing presence of private space companies, which don’t appear to face the same budget windfalls or political concerns. Morgan Stanley estimated in July that the global space industry could generate more than $1 trillion in revenue in 2040, compared to the $350 billion estimated in 2020. Space Capital, a seed-stage venture capital firm focused on the space economy, also reported last month that investors poured $15.7 billion into 252 space companies in 2020, including $9.4 billion to U.S. companies.

That outpouring of funds is showing in private space companies’ more ambitious goal posts. For example, SpaceX Inc. Chief Executive Elon Musk said in December that he is “highly confident” that his company will be able to land humans on Mars by 2026, and he’s gone as far as estimating that SpaceX could send 1 million people to the Red Planet by 2050. And Amazon.com Inc. CEO Jeff Bezos plans to dedicate more time to his space company, Blue Origin, once he leaves his day-to-day role at the e-commerce giant later this year.

While most adults (54 percent) are bullish that humans will be able to routinely send civilians to space as tourists in the next 50 years, they’re not so sold on going into space themselves. Fifty-eight percent said they were either “not too likely” or “not likely at all” to travel to space if price weren’t a concern, up 10 points from the 48 percent who said the same in a September 2017 Morning Consult/Politico poll.

When asked if they would be willing to spend more or less than the price of an average airplane ticket to go to Mars, 53 percent said they were not interested at all in space travel.

Those numbers change slightly based on gender and age. More men (44 percent) said they were likely to embark in space travel if price weren’t a concern, than women (23 percent), while the idea of traveling to space was more popular among Gen Z (46 percent) and millennials (49 percent) — compared to 32 percent of Gen X adults and 19 percent of baby boomers.

Making space exploration a priority though, even during a pandemic, could bode well for Americans’ morale, Logsdon said, such as what happened with the first moon landing in 1969 that came on the heels of a decade of domestic and international civil unrest.

“It was a counter balance to the negativity of the time,” Logsdon said. “If we do inspirational things in space -- go back to the moon or travel beyond land rovers on Mars -- that gives us a sense of future, a sense of positive achievement to counter the pervasive negativity.”

Sam Sabin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering tech.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade