Tribal Lands Lag on Internet Deployment. Local Efforts, Not Government Intervention, Is Providing a Path Forward in Some Cases

Key Takeaways

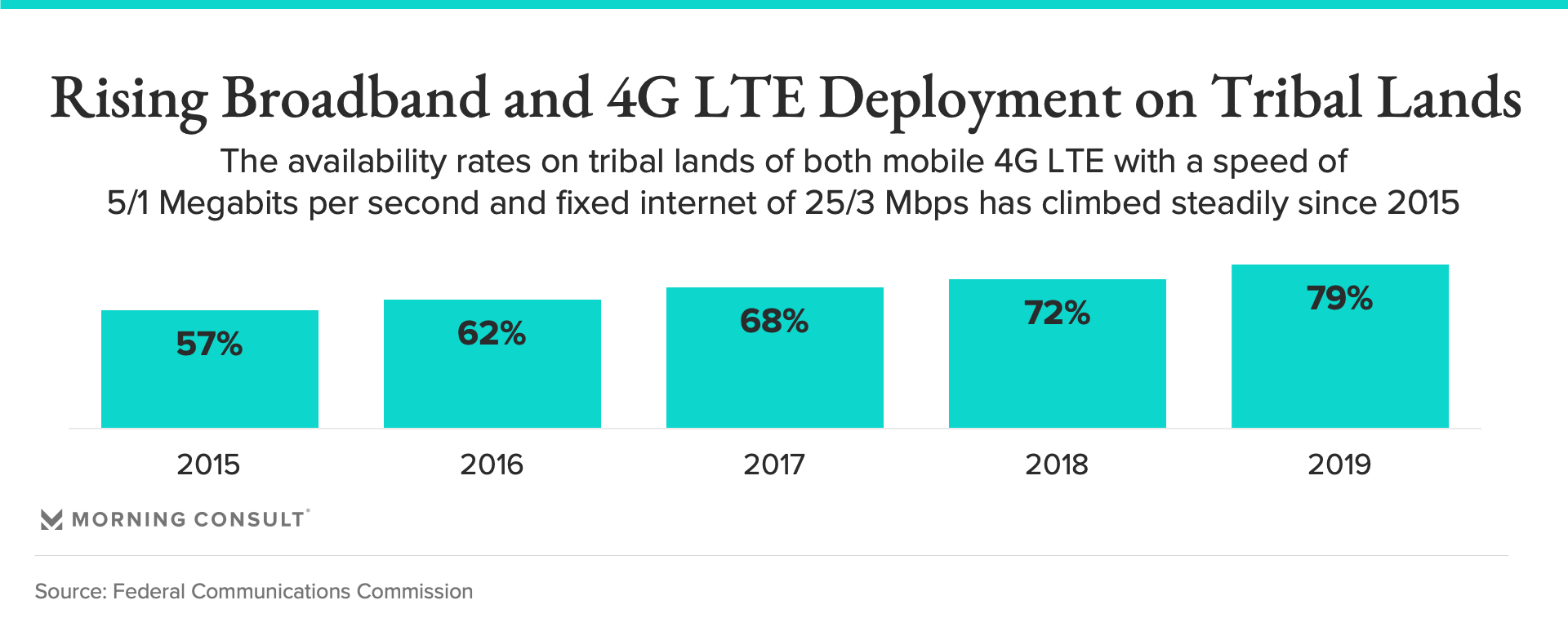

As of 2019, 79% of tribal lands had both broadband internet and 4G LTE available, compared to 96% of the overall population, according to a Federal Communications Commission report.

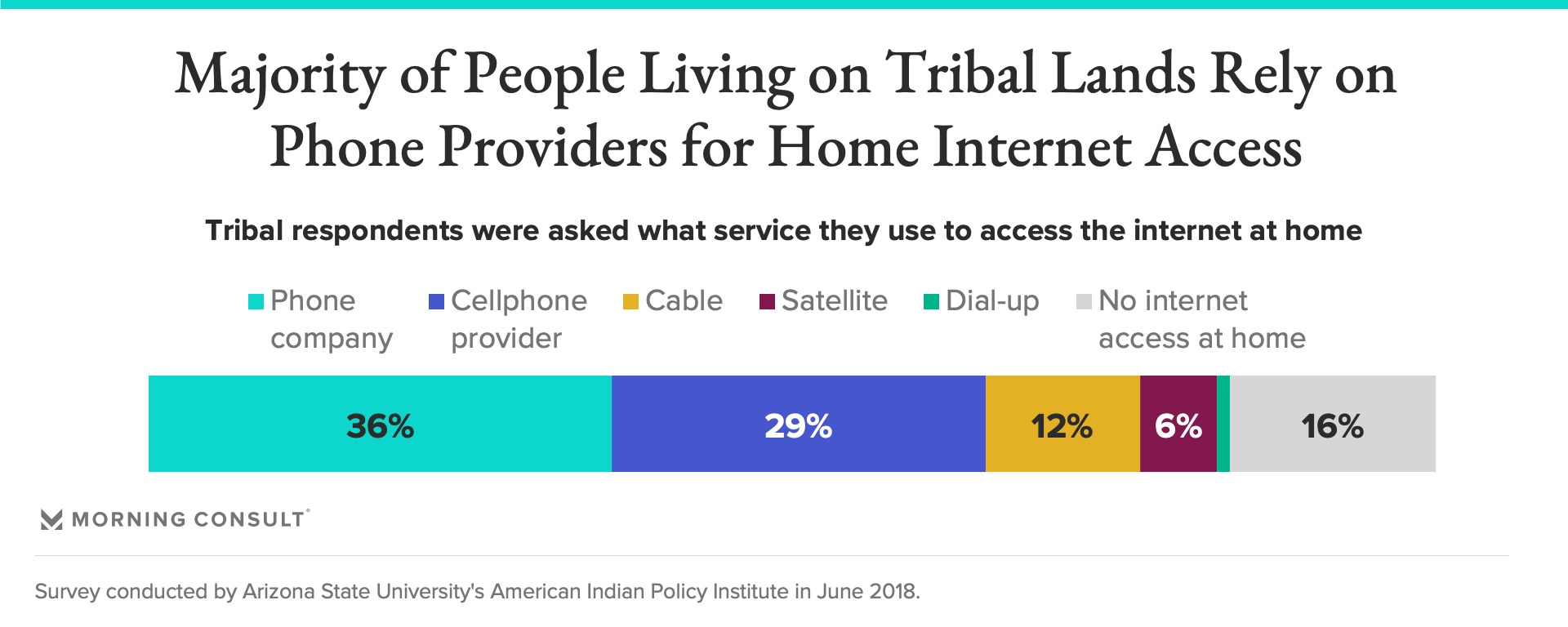

A 2018 American Indian Policy Institute survey found that 36% of those living on tribal lands access the internet through their phone company, compared to just 12% that use cable access, while 1% still use dial-up.

Local communities have taken matters into their own hands by establishing their own networks, which typically are not profit-driven.

The digital divide facing tribal communities is stark and has remained pronounced despite the best efforts of advocacy groups and tribes themselves to help Indigenous people get online.

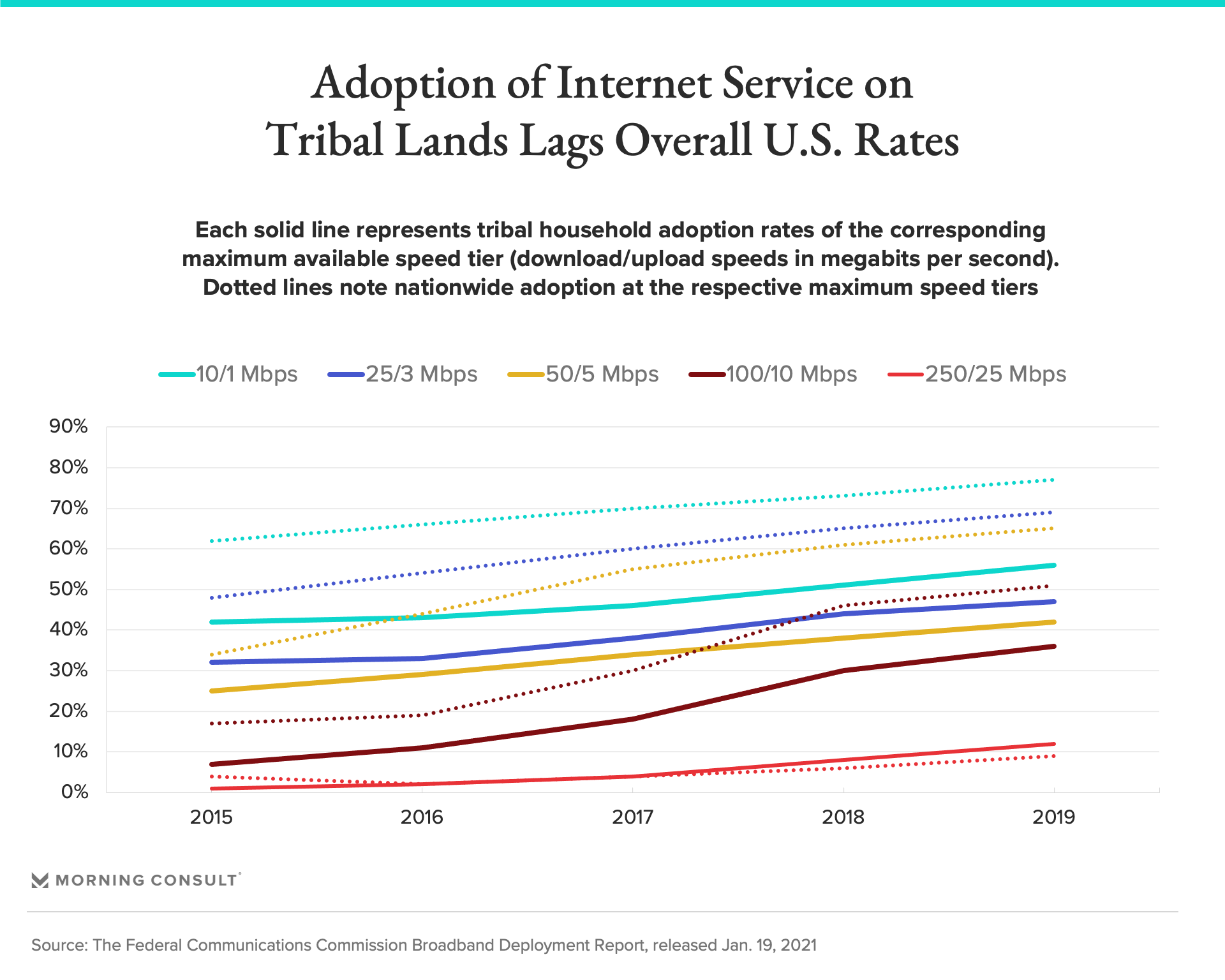

According to the Federal Communications Commission’s 2021 Broadband Deployment Report, just under 47 percent of households on tribal lands in 2019 had access to maximum broadband speeds at the FCC's current benchmark of 25 megabits per second download speed and 3 Mbps upload speed.

Many tribal leaders are not waiting for the federal government or the private sector to intervene, as planned investments would do little to address the gaps in coverage. Instead, they are going it alone in their communities by building out their own networks to get their residents connected.

With jobs, schooling and health care going remote during the coronavirus pandemic, faster internet speeds can help prevent people in remote communities from falling behind -- and setting up local networks are often key to attracting more jobs and economic development to the areas where they operate.

The efforts of Indigenous leaders, like others around the country, come as deployment of fixed and mobile broadband has remained sluggish on tribal lands. As of 2019, only 79 percent of tribal lands had both broadband internet and 4G LTE available, compared to 96 percent of the overall population.

“I think everybody for the longest time was waiting for the federal government to solve it because they're supposed to; that's their trust responsibility,” said Matthew Rantanen, director of technology for the 24-tribe Southern California Tribal Chairmen’s Association. “And they didn't. I think there was a lot of, ‘Well, why are we doing this ourselves? We're just wasting money when the feds are going to do this anyway.’ But there was no obvious path, and it wasn't happening.”

A ‘bleak picture’ on tribal access

In testimony before the House Natural Resources Committee’s Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples of the United States earlier this year, Dr. Traci Morris, executive director of the American Indian Policy Institute at Arizona State University, said the limited sources on tribal broadband deployment paint a “bleak picture.”

An AIPI survey showed that in 2018, 36 percent of respondents access the internet through their phone company, compared to just 12 percent who have cable access, while 1 percent said they still use dial-up internet. Meanwhile, 29 percent access the internet through their cellphone provider.

While statistics are scarce on the economic impacts on tribal lands from a lack of connectivity, the effects more broadly are notable.

A research paper prepared for the International Telecommunications Society found that increasing mobile broadband speed by 10 percent leads to a 0.2 percent boost in a country’s labor productivity the following year compared to what it would expect otherwise. The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation said that trend would be “even more pronounced” in the pandemic due to the shift to remote work.

More help may be on hand for tribal communities after President Joe Biden signed the infrastructure bill earlier this month. Included in the legislation is $65 billion in grants to expand broadband internet access, especially in rural and tribal areas.

Where infrastructure lacks, communities fill in the gaps

Tribal lands lack much of the infrastructure for broadband and mobile internet, while the federal government’s data collection and mapping to show deployment is inconsistent and inadequate. The lack of infrastructure is partly attributed by many experts to telecommunications companies not being able to receive a return on their investment if they put in cables or mobile towers due to a lack of customers.

Brian Weiss, a spokesperson for USTelecom -- The Broadband Association, which represents broadband providers, pointed to the trade group’s support for universal connectivity during debate over the just-passed bipartisan infrastructure bill. The group said in a statement in early November that broadband providers have built a “networking miracle” that proved itself during the pandemic but that “targeted public support” is needed to connect the hardest-to-reach areas.

Given the challenges that exist, local efforts have been more effective in helping to get some Indigenous communities more connected, including in the Hawaiian village of Pu`uhonua O Waimanalo on the island of O’ahu. Brandon Maka’awa’awa, deputy head of state of the sovereign Nation of Hawaii, helps manage the Pu`uhonua O Waimanalo Community Broadband Network, which connects the village to the internet.

Maka’awa’awa said some residents subscribe to the community network, which residents connected to a Hawaiian Telcom fiber access point and maintain, with the company among the partners on the project along with others elsewhere. While Weiss did not comment specifically on these efforts, he pointed to a USTelecom statement that said local governments are “focused on governing” and building static infrastructure like roads and bridges, and local networks “frequently have struggled to remain solvent.”

The Pu`uhonua O Waimanalo group first got the community hall connected to the fiber by digging a trench themselves and laying down cable, then getting households connected wirelessly by using LTE over unlicensed spectrum. Maka’awa’awa said the aim is to connect every household to the internet while not concerning themselves with making a profit on subscription fees.

Others have seen success through community networks for their rural and Indigenous communities, while in Hawaii it is viewed as a way to empower those communities.

Local residents have used the network to buy and sell goods and create apps, in addition to helping educate others about their heritage and history. That local connection is key, Maka’awa’awa said.

“We're not doing it for money,” he said. “We're doing it so that we can have reliable internet service, which is very important, and sometimes it supersedes the economic benefit that we get from it.”

Similarly, the Southern California Tribal Chairmen’s Association took advantage of a grant from Hewlett Packard Enterprise Co. in 2001 to start the Southern California Tribal Digital Village. The village first delivered wireless broadband to its various government buildings, then to around 450 homes by connecting to existing internet access points and running infrastructure back to its tribal lands.

In addition to investing in the infrastructure and technology necessary to get people online, Rantanen said there also needs to be an effort to improve people’s digital skills so they can take full advantage of their internet connection. That can also mean helping maintain local networks, he said, and young people on tribal lands should be made aware of those opportunities sooner.

“Somewhere along the path, tribal youth are not getting access to technology as a career field, or even just an employment opportunity field,” Rantanen said. “They're not getting baseline understanding of not just using a computer, but maybe stepping into the next realm of utility, or the greater concepts around computing, like networking.”

Spectrum as a ‘natural resource’

More work lies ahead, however. The Government Accountability Office has previously criticized the FCC for not doing more to help tribal communities get better access to spectrum, especially when it is available over their lands. FCC spokespeople did not respond to requests for comment.

Rob McMahon, an associate professor at the University of Alberta whose research focuses in part on the adoption and use of broadband internet and related technologies by rural and Indigenous communities, said there is an emerging trend among Indigenous communities to assert sovereignty over spectrum when it is over their lands, and compete more in FCC auctions.

That push entails looking “at spectrum more as a natural resource, and then that ties into Indigenous rights and jurisdiction,” he said. “And then therefore, that becomes part of their ownership or stewardship of that resource in their territories. It's a different way to think about spectrum.”

And McMahon said Indigenous communities have been innovative users of technology for decades, including from the early stages of the internet and by creating community radio stations. That creativity will stand those communities in good stead, he said, for future efforts to get residents connected.

“I think often there's that stereotype that Indigenous peoples are stuck in the past or something,” McMahon said. “But that's very much not the case. They're often highly skilled and successful innovators in new technologies, and then also when you look at usage stats, when the community actually gets connected, it's crazy. The uptake is just wild to watch.”

Correction: The original version of this story said that 47 percent of households on tribal had broadband access according to the FCC's definition of the term: 25 megabits per second download speed and a 3 Mbps upload speed, but failed to note that the 47 percent share also includes households with slower speeds of 10/1 Mbps.

Chris Teale previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering technology.