Biden’s Pivot to Asia Has a Crucial Latin American Component That’s at Risk of Neglect

Key Takeaways

The upcoming Summit of the Americas was meant to be the Biden administration’s big opportunity to share a vision with Latin American neighbors that addresses development, democracy and deepening regional integration. Instead, major boycotts around invitations and criticism of the agenda threaten to embarrass the administration.

China, meanwhile, stands to gain from the United States’ attention deficit over the concerns of its nearest neighbors as Beijing’s direct investment in the region’s natural resources and infrastructure deepen relations and fill coffers.

U.S. President Joe Biden’s recent visit to South Korea and Japan fulfilled its intended purpose of rallying allies and displaying a united front against Chinese aggression, demonstrating the administration’s capacity to pull off some tricky diplomacy when it sets its mind to it.

But in Latin America, the picture is markedly different: Despite its increasingly close trade and investment ties with Beijing, the Biden administration’s pivot to Asia seems to have swung right past the region. And there is no more public example than the Summit of the Americas, set for June 6-10 in Los Angeles.

The White House was caught on the back foot when Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador announced he would not attend if the leaders of Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua were not invited because of their human rights records, which the leaders of Honduras and Bolivia quickly echoed.

Special adviser Christopher Dodd was quickly dispatched by the White House for talks with López Obrador, and the administration is said to be evaluating ways to incorporate "the voices of the Cuban, Venezuelan and Nicaraguan people into the summit process." Nonetheless, Cuba said it would not attend in any capacity since it was not on the original invitation list.

Heidi Smith, a research professor in the economics department at Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City, who used to work in the State Department bureau that organizes the summit, pointed to the rushed timeline as a key factor in the missteps that have followed.

“The naming of Los Angeles to host the summit was six months out. We usually have two years of consultations across the hemisphere, and the host country organizes those consultations, but the United States hasn’t had enough preparation and planning time for this summit,” she explained — but that’s not flying for some critics.

“It’s amateur hour in Washington,” said Jorge Heine, who served as Chile’s ambassador to China from 2014 to 2017. “The summit would have been the ideal moment for Biden to mark the difference between his approach and the approach of the Trump administration, which was a total disaster, but the opportunity was kicked down the road for a year and a half. It wasn’t held because the administration had other priorities.”

A National Security Council spokesperson declined to comment on the record for this story.

Latin America’s deepening relationship with China

The White House has been proactive in checking China with multilateral action in Asia but has made few public pronouncements about Beijing’s influence in Latin America.

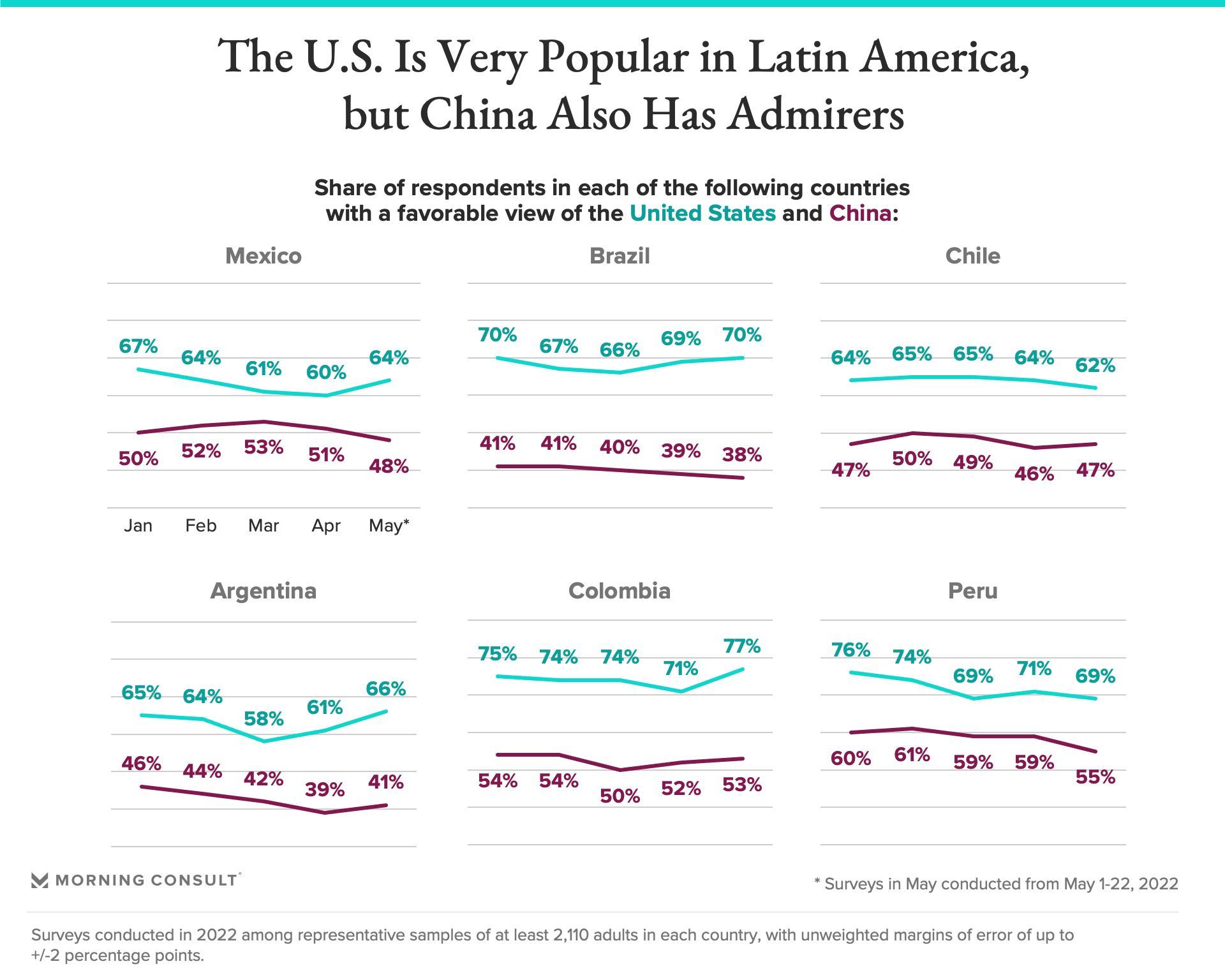

The United States is very popular across the region, but China is no slouch, especially given its relatively recent arrival on the Latin American diplomatic and commercial scene at the turn of the 21st century. Between 2000 and 2020, Chinese trade increased from 1.7% to 14.4% of the region’s total trade and had reached nearly $450 billion by 2021. Meanwhile, Chinese direct investments have made up 10% of total inflows in recent years.

“A Summit of the Americas that either does not take place or is missing some of the key regional partners would be a boon to China,” said Arturo Sarukhan, a former Mexican ambassador to the United States. “China's clapping on the sidelines that all of this is happening because it obviously feeds into its very significant investment in public diplomacy and soft power in the region.”

Beijing no longer opts for the sort of bilateral lending schemes, organized through political relationships, that drew some attention in official circles during the Obama administration, according to Pepe Zhang, associate director and fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. Instead, it is becoming an increasingly sophisticated and significant player in the field of foreign direct investment, where Latin America’s wealth of natural resources and significant infrastructure deficit offer lucrative prospects for both sides — ripe territory for some of the “win-win” diplomacy China has tried to emphasize in what it calls “South-South cooperation.”

“In Latin America, people want to have better relations with the United States, but their main concern is development, and on that front, China is delivering,” said Heine. “What people find disconcerting is the U.S. approach of telling governments in the region not to do business with China. Their response is, ‘Well, what do you offer?’ And for far too long, the U.S. response is, ‘We're not offering anything; we're telling you what to do.’”

Beijing takes a softer touch

On the other hand, Beijing tries to keep great-power disputes from getting in the way of productive relations.

“China goes out of its way to make sure its loans don't have political attachments,” said Harold Trinkunas, deputy director and senior research scholar at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation. “There’s not political conditionality like you get with the United States; you know, ‘Increase your budget surplus so you can pay your debts’ — the kind of advice that rubs people the wrong way.”

Like most middle and developing powers, Latin American governments generally prefer to look after their own interests first and stay out of major geopolitical disputes, which China seems to find to its benefit. Mariana Campero, senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Americas program and former CEO of the Mexican Council on Foreign Relations, pointed out that while some members of López Obrador’s coalition have advocated for closer ties to China on leftist ideological grounds, Beijing has not reciprocated.

“China is smart enough to know that they don't want to piss off the U.S.,” she said, adding that Mexico also competes with China in manufacturing, making close relations less appealing for Beijing.

However, China isn’t afraid to make soft-power plays when it sees a good window, as Beijing did during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, first by providing personal protective equipment to multiple Latin American countries and then by sharing vaccines when the United States and Western Europe were hesitant to do the same.

The United States has the ways. Can it find the will?

Still, surveys of residents in Latin America’s four largest economies show a clear preference for investment from U.S. companies over their Chinese counterparts when they can get it.

Latin Americans Prefer Infrastructure Investment From U.S. Companies Over Those From China

In each country, China came last behind the United States and European Union, and no more than a quarter of respondents in each country ranked it as their top choice of investor. U.S. companies, on the other hand, aren’t as enthusiastic.

“The fact of the matter is that U.S. companies are not into building infrastructure in Latin America,” said Heine. “They don't participate in tenders. They dismiss it; they are not interested. It is the Chinese companies that are willing to participate in bids for $100 million or $150 million projects.”

Working with China can also be easier because state-owned firms and banks cut down on red tape and speed up delivery timelines, but at least one expert interviewed for this story pointed out that U.S. institutions like the Development Finance Corporation, Millennium Challenge Corporation, and Trade and Development Agency work hard behind the scenes to encourage U.S. investment.

“We have much more leverage than China because we have more feet on the ground and more engagement with the region,” said Smith of Universidad Iberoamericana, adding that the United States’ goals are not simply transactional: “We're pro-capitalist, we're pro-market, and it's not just that we are collaborating to create more tenders; we're also collaborating to strengthen the capitalist systems in the region.”

That bureaucratization of foreign relations is most evident in Mexico, which provides the best example of what’s at stake if relations with Latin America are left on autopilot.

“Mexico has a substantive agenda with absolutely every single government agency in Washington, D.C.; very few countries have that. And it's precisely that architectural framework that allows both countries to more or less maintain the relationship on an even keel despite the issues that are playing out,” said Sarukhan, the former Mexican ambassador. “But the problem is, if you don't invest additional political and diplomatic bandwidth in the relationship and use this juncture to really deepen that edifice, it could jeopardize the most important recalibration of U.S. foreign and national security policy since the end of the Cold War, with regard to decoupling from China.”

Mexico would play a crucial role in “friend-shoring” U.S. supply chains currently running through China because of its proximity and access to U.S. markets through the USMCA, but such a major shift is difficult to pull off without high-level political dialogue. Carin Zissis, editor-in-chief of AS/COA Online, said the selection of Los Angeles to host the Summit of the Americas was in part meant to underline Mexico’s importance, given L.A.’s deep historic and cultural ties with the country.

Nonetheless, Heine said the guest list sent a stronger message than the host city as the region finds itself dealing with high inflation, political instability and democratic backsliding.

“There was a great opportunity to focus on the crisis and how to get out of it. Yet what is the main priority? To exclude three countries. Is there no memory at the State Department?” he asked rhetorically, explaining that the 2012 summit also nearly collapsed because of Cuba’s exclusion. (Cuba participated successfully in 2015 and 2018.)

Experts were also cognizant that normalizing relations with Cuba, opening up the U.S. market to Latin American imports and ending Trump-era migration policies are not perceived to be winning electoral moves for Biden or the Democrats and that the invasion of Ukraine has demanded urgent attention from the White House.

“President Biden is fighting on a number of global and regional fronts with one hand tied behind his back because of the profound polarization that is occurring in America today, politically, electorally and socially,” said Sarukhan. “There's always been a structural lack of attention by the U.S. to the Americas, but the current circumstances explain why it's hard for the U.S. to play the type of role that China is playing in the hemisphere.”

Latin America, and Chinese influence therein, will still be a pressing concern when the fighting in Ukraine stops, and a breakdown in high-level dialogue between the United States and the rest of the region can only strengthen China’s hand as it looks to fill any potential vacuum.

Matthew Kendrick previously worked at Morning Consult as a data reporter covering geopolitics and foreign affairs.