At the Crossroads of the World, Turkey Charts Its Own Course on Ukraine

Key Takeaways

Turks are relatively unenthusiastic about sanctions on Russian oil and gas, as well as the idea of shipping weapons to Ukraine, as Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan seeks to assume the role of mediator between Turkey’s Black Sea neighbors.

Twice as many people in Turkey identify with the West as with Russia, but the largest group (45%) in the NATO member country were either unsure or had no opinion on the question.

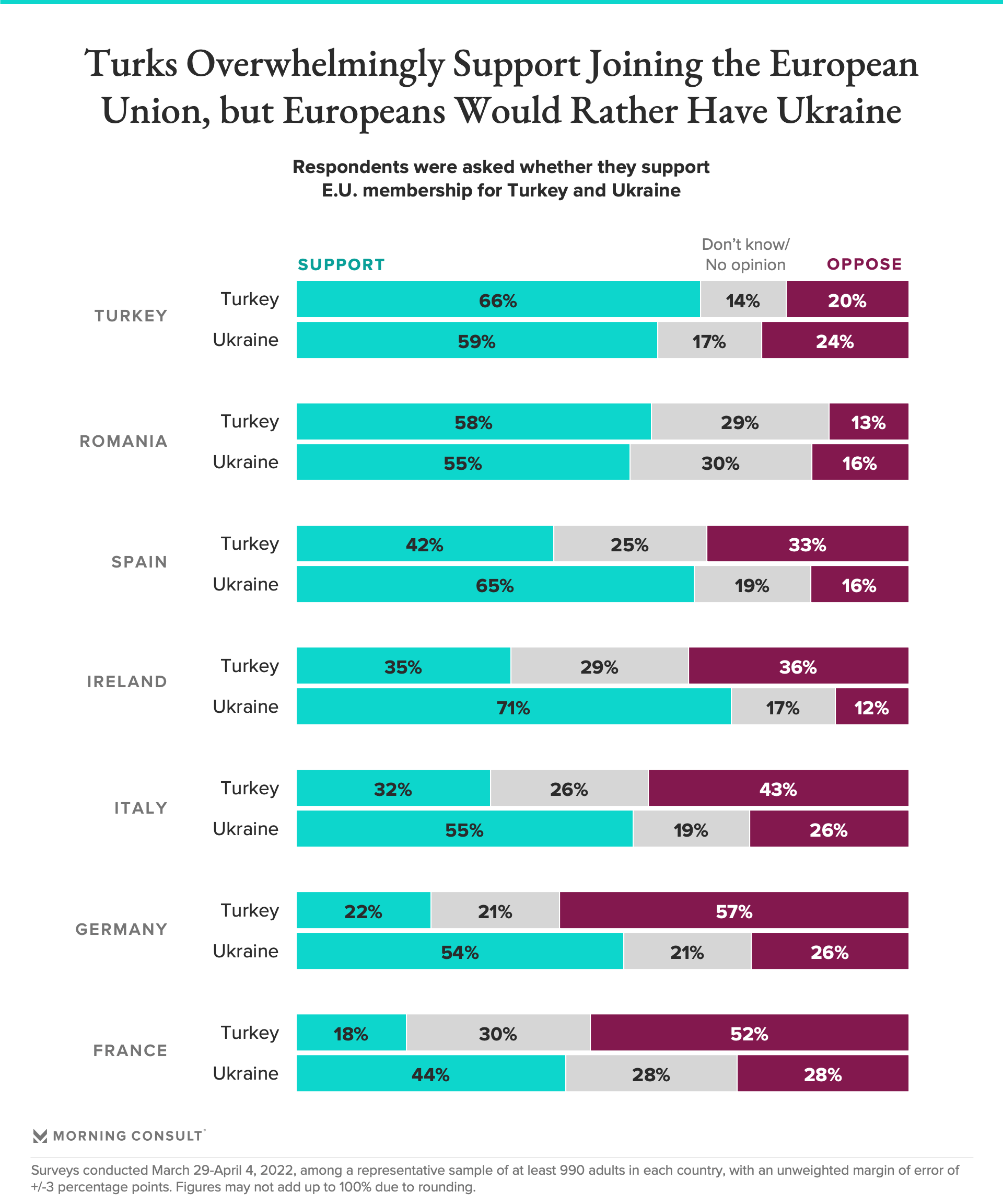

Two-thirds of Turks want to join the European Union, but Europeans themselves are not thrilled about the prospect — and political realities make integration unlikely.

After almost a decade of increasingly blossoming ties with Moscow, Turkey surprised some by leaning heavily toward the West after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But experts say not to misread that as a shift in foreign policy, with the lion’s share of Turks saying they are aligned to neither power and Ankara unlikely to give up its strategic independence any time soon.

Turkey’s growing relationship with Russia has caused no small amount of consternation among other NATO allies, but the country has come through for its Black Sea neighbor Ukraine in some big ways since the Feb. 24 invasion, becoming one of its leading arms exporters.

That has occurred despite its role as mediator in peace talks between Russia and Ukraine, and amid resistance among the Turkish public: Ukrainian troops may love their Turkish-made Bayraktar drones that wreak havoc on Russian units, but Turks themselves are less sure about the wisdom of arming Kyiv.

Turkey has so far avoided joining Western-led sanctions against Russian energy exports, though, and Ukrainians probably should not expect that to change any time soon. Only 15% of Turks — hurt by inflation rates as high as 61.14% recently — are willing to put up with price increases associated with sanctions.

Turkish history and regional geopolitics on Europe’s eastern fringe has also gotten in the way of extensive entanglements, with Ankara keen to be involved but anxious about the fallout of conflict in its own neighborhood, said Visne Korkmaz, a specialist in Russo-Turkish relations at Nisantasi University in Istanbul.

“Turkey does not want to see the crisis turned into a tool of punishment for Russia,” she said, explaining that Turkey, even as a member of NATO, was reluctant to become caught up as a player in a dispute that it sees as primarily between Russia and the West.

“Because of its experience with neighboring states since the 1990s, Turkey has long since reached the conclusion that it should try to prevent crises from turning into war,” she said. "Unfortunately, the war in Ukraine is not an issue stemming from Turkey-Russia relations; it is, even more than a Russian-Ukrainian issue, an issue between Russia and the West.”

Independence, Istanbul-style

Turkey’s more independent reaction to the Russian invasion has also not been by chance.

Its approach to the Ukraine crisis has been a demonstration that President Recep Tayyip Erdogan now feels perfectly comfortable walking out of step with Washington and Brussels — and even Moscow — according to Jeffrey Mankoff, a distinguished research fellow at the U.S. National Defense University’s Institute for National Strategic Studies.

“The West is going to have to get accustomed to dealing with a Turkey that's more of a regional power rather than a Western power,” said Mankoff, who stressed he was speaking in his personal capacity, not on behalf of his university or the U.S. government. “Which is not to say that it's anti-Western, but Turkey's policy is to consolidate its own interests within the region, and to play an independent role.”

In fact, that quest for strategic autonomy was a major factor in bringing Moscow and Ankara closer in the first place, said Mankoff, who pointed to U.S. policy in Syria and America’s response to the alleged 2016 coup attempt against Erdogan as major factors.

“In both of these instances, leading members of [Erdogan’s] AK Party perceived the West as not taking Turkey’s legitimate national security interests into consideration and this pivot towards Russia was effectively a way of trying to gain room for maneuver,” he said.

Notably, Turkey purchased Russian S-400 anti-aircraft missiles, unsatisfied with relying on American-made and NATO-controlled Patriot missile systems for its air defense. Turkey also cooperated with Russia and Iran to organize the Astana talks toward peace in Syria. There, American support for the Kurds put Washington in direct conflict with Turkey’s unflinchingly anti-Kurdish policies.

However, Vali Nasr, professor of international affairs and Middle East studies at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, pointed out that Moscow hasn’t always been pleased with its new relationship with Ankara.

“Erdogan was being opportunistic in reaching out to Russia, and it’s not like he has been an ally,” Nasr explained. “They didn’t always see eye to eye on Syria or Libya, for example.”

When Azerbaijan, a Turkish ally and former Soviet republic, invaded the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region then administered by Russian ally Armenia, Ankara didn't hesitate to step in with support. Turkey aided Azerbaijan’s war effort with operational advice from senior military figures and deadly Bayraktars.

Still, that didn’t mean an end to the Russo-Turkish relationship.

“They have managed to compartmentalize their disagreement,” said Mankoff.

History doesn’t repeat (but sometimes it rhymes)

Few ordinary Turks feel an affinity toward Moscow. In fact, more than twice as many said they identify with Western interests — but nearly half either had no opinion or were unsure of their bent.

Turks Are Twice as Likely to Align With the West Than With Russia — but Even More Can’t Say

“There's a lot of fear of Russia that in part goes back to their long history of conflict,” said Mankoff. Since the 17th century, Turkey and Russia have gone to war no fewer than a dozen times and, Mankoff said, “in almost every one of those wars, Russia won and Turkey lost, except when Turkey had alliances with other major powers, like in the Crimean War.”

Ukraine has also presented Turkey a chance to demonstrate its indispensability to the West.

“The war in Ukraine immediately increased Turkey’s value to Europe and NATO,” said Nasr. “At a time when NATO has rediscovered its original purpose, and escalation with Russia is a real possibility, the largest land army in NATO after America’s is Turkey’s.”

Korkmaz noted that Ankara has long pushed its allies to recognize that any plans for European security must include Turkey. After all, it controls the only access to the Black Sea, and has already exercised its rights under the Montreux Convention to close the Bosphorus, which separates Europe from Asia, to warships.

“Turkey’s link to Western identity is not related to culture but instead the historical experience of geopolitical security,” she said. “Turkey has been part of the European balance of power for centuries; this is one of the pillars of our political tradition.”

In two worlds

Being integral to Europe and yet not a part of it seems likely to continue for Turkey, however much Russia’s invasion nudges its security interests westward.

Although two-thirds of Turks say they would like to join the European Union, among European populations, only Romania — another country on the front lines with Russia — reciprocates Turkish sentiment with majority support. Meanwhile, Turkey’s accession is described by the European Commission as “effectively frozen.”

Europeans in general are considerably more ready to welcome Ukraine to the bloc — though the chances of that happening are no more likely in the short term.

Beyond that, cultural roadblocks between European and Turkish integration still exist.

“If you were to ask Turks, ‘Are you willing to be part of the E.U. and be less Islamic?’ I'm not sure the answers would be as straightforward,” said Nasr.

Korkmaz pointed out bigotry against Muslims was not an abstract fear.

“We still don’t know the results of the French elections, and whether the far-right’s anti-Islamic, anti-Turkish, anti-non-Western rhetoric will win out,” she said.

From Brussels’ perspective, the math of bringing Turkey into the fold doesn’t add up either.

“Turkey is not only Muslim, but it's big; it would be the largest country in the bloc. It's also relatively poor and there aren't any large, poor states in the E.U.,” said Mankoff. “On top of that, how comfortable is the E.U. having its external frontiers extend to Syria, Iraq and Lebanon?”

But even if barriers to integration to the European Union seem insurmountable, that doesn’t mean there isn’t any common ground within the limits of each side’s interests.

In many ways, the Ukraine-Russia conflict may have demonstrated that Turkey’s status as a more autonomous actor within the NATO security bloc — but still only on the periphery of the European Union as a political project — might still make the most sense.

“Europeans don't want to continue conflict with Russia. The war has created huge costs for them and they want to restore balance of power and deterrence against Russia, which creates a convergence of interests between Turkey and the West,” said Korkmaz. “The best way forward is through NATO, understanding that Turkey's security is also directly related to Western security.”

Matthew Kendrick previously worked at Morning Consult as a data reporter covering geopolitics and foreign affairs.