Xi Put ‘No Limits’ on China’s Support for Russia. He Might Be Regretting That

About this article

This article is part of a series exploring how Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is altering its relationships with its relatively few allies. See our deep dive on the implications for Iran.

Key Takeaways

While sentiment on Chinese social media about the war in Ukraine is strongly pro-Russian, government officials have been more circumspect, expressing regret for the conflict and offering to play the role of mediator to find peace.

China finds itself strategically stymied, forced to reassess its assumptions about democracies, Western decadence and the feasibility of reunifying Taiwan by force or attempting to take control of the South China Sea.

The United States could seize a brief window of opportunity to influence Beijing while it searches for a new course, experts say, and to signal a NATO-like solidarity and cohesion among U.S. allies in Asia.

U.S. President Joe Biden will speak with Chinese President Xi Jinping on Friday at a crucial moment for Beijing, as China’s assumptions about its relations with both Russia and the West unravel and force major reassessments of grand strategy.

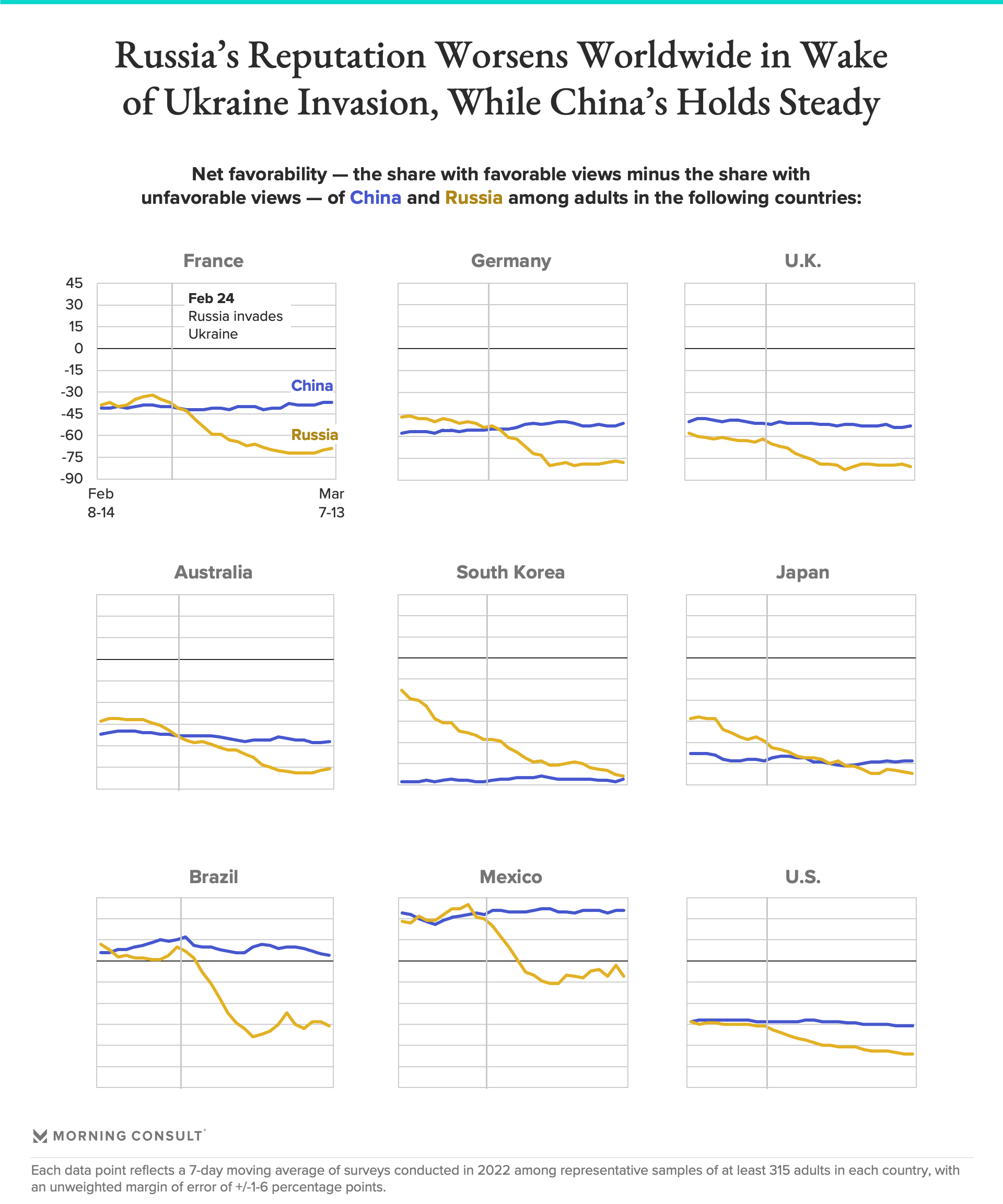

China has so far avoided a decline in its global favorability even as Russia’s has sunk, with Western governments refraining from assigning China culpability for the war in Ukraine despite Beijing’s and Moscow’s touting of a “no limits” relationship just before the invasion.

But the worldwide opprobrium in the wake of the devastation in Ukraine — and threats of “consequences” for Chinese collaboration from the United States — has also put Beijing in a difficult position as it assesses how much it can afford to support its only major ally.

Mixed messages

Turning on Chinese state television or flipping through the People’s Daily, coverage of murdered civilians or cities crushed under Russian bombardement is few and far between as state-owned media seeks to downplay the brutality of the war without overtly condoning it. But scroll down to the comments section or log on to the Twitter-like social network Sina Weibo — both carefully moderated by Chinese censors — and there’s no shortage of fiery condemnation of the U.S. or pro-Russian talking points.

It all points to growing uncertainty in the Middle Kingdom over how to approach Ukraine.

“I don’t think China has clearly picked a side yet,” said Tracy Wen Liu, a freelance journalist and translator who reports on China’s media scene. “Official statements say ‘We want peace, we respect Ukraine and Russia as countries, we don't want escalation’ but they write them intentionally in a way that doesn’t convey much information.”

Liu said the early pro-Russian and anti-American bent of social media reaction to the war was a reflexive response driven by longstanding efforts to engineer public opinion from Beijing.

“They want people to believe that all the problems that exist in China are ultimately caused by the U.S.,” Liu said, even if that currently clashes with Beijing’s official positions.

Matt Schrader, an adviser at the International Republican Institute’s Center for Global Impact, bluntly described China’s public offers to play mediator between Russia and Ukraine as evidence of a still indecisive approach to an unexpected predicament.

“Nobody is preventing China from attempting to mediate,” Schrader said. “It's an effort to create the perception among foreign interlocutors that China is necessary and essential to the conversation, even if it's not actually entirely clear what China will contribute.”

No good options

This comes amid growing evidence that Beijing miscalculated in its strategic approach to Russia, the only major power with which it is close.

“Until the minute that Russia's tanks crossed into Ukraine, the Chinese foreign minister was on television saying that there's not going to be an invasion,” said Craig Singleton, a senior Fellow at the Washington-based Foundation for Defense of Democracies. “From the Chinese perspective, Putin had Ukraine right where he wanted them: He had ratcheted up the pressure at almost no cost to him, and it was likely going to yield a concession.”

China’s leadership, he said, would have been content to walk away at that point, but failed to understand that doing so would not meet Putin’s strategic ambitions. Now, Beijing stands to gain very little by becoming more involved in the situation, even if it tries to ease into a more neutral position.

“Say Xi is able to mediate: He will have done so at the expense of the Russians, who will need to concede something because they're being told to by the Chinese, and that's going to build incredible resentment,” said Singleton, adding that the alternative was even less face-saving for the two leaders. “The other scenario is that China is unable to mediate some sort of resolution, at which point Xi is just a bystander incapable of influencing great power politics.”

But Schrader notes that not supporting Moscow presents an even more terrifying prospect for Beijing: regime change.

“In Moscow this is becoming potentially life or death for Putin's regime. And Beijing doesn't know what the day after looks like,” he said. “Is Putin’s replacement somebody who is as friendly to Chinese interests? Or do you get somebody who's more E.U.-U.S. aligned, or God forbid, a transition to something like a representative democracy?”

Never let a crisis go to waste

The dilemma for Xi could provide an opening for Biden.

The Ukraine war is forcing Beijing to reassess its geopolitical priorities and prior assumptions about democracies, as well as the cohesion of America’s global alliances. That opens a limited window of opportunity for Washington to influence the direction of Beijing’s new tack, according to Ryan Hass, who served as a staff director for China, Taiwan and Mongolia at the National Security Council from 2013 to 2017 and is now senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center for East Asian Policy Studies.

“We're in a moment of fluidity where the Chinese are taking in new data and trying to figure out how it impacts them,” Hass said. “We're not going to be able to drive a wedge between China and Russia or anything like that. It's going to be progress measured in degrees — three degrees, four degrees, five degrees of separation — but in diplomacy that's a good day of work.”

Washington now has a chance to press Beijing against supporting Russia militarily, he said, but could also ask Beijing to privately warn Moscow against killing civilians, among other priorities.

Xi’s ambitions to bring Taiwan back under mainland control are also being forced back to the drawing board as Ukraine’s tenacious defense of its borders challenges assumptions about what conventional military operations can achieve even with massive asymmetries.

But while that might lead to China’s plans for Taiwan — as well as for the South China Sea and the Himalayan border with India — being put on ice for a while, Hass pointed to another troubling lesson from the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

“The war is validating China's view of the importance of nuclear weapons because it’s shown having a credible nuclear threat is a pretty good deterrent for outside intervention in conflicts, which is what China would like in the case of Taiwan,” he said.

Yet in the West’s united response to Ukraine, Beijing will be looking nervously at its neighbors.

In South Korea and Japan, China was already viewed as poorly as Russia currently is, with things only slightly better in Australia. All would be key to any U.S.-led efforts in Asia, noted Singleton of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

“That should ring alarm bells in Beijing about how terribly China is viewed and how very fast their fortunes could get even worse if they were to do something aggressive like retaking Taiwan by force,” Singleton said.

Matthew Kendrick previously worked at Morning Consult as a data reporter covering geopolitics and foreign affairs.