61% of Voters Say They Believe Russia Will Try to Interfere in 2020 Election

Key Takeaways

61% also said they would be more likely to vote if an outside actor interfered in 2020.

44% of Republicans said Russia would try to interfere in 2020 vs. 25% who said the same about the midterm elections.

With less than six months until the first presidential primary vote is cast in Iowa, more voters are saying it’s likely that Russia will try to interfere in the next presidential election, according to a recent Morning Consult/Politico poll. But the survey suggests that the prospect won’t deter them from heading to the ballot box.

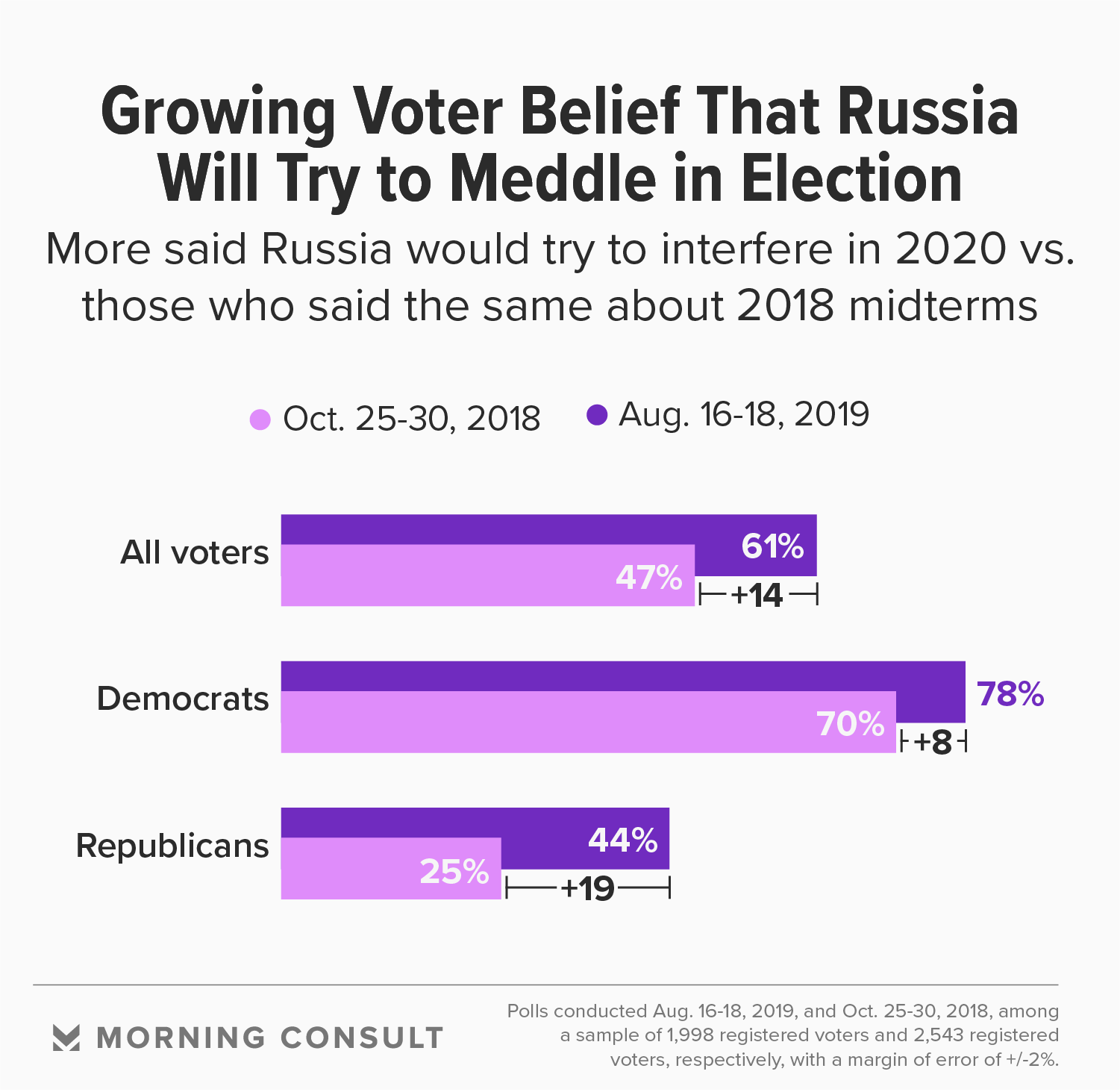

According to a survey conducted Aug. 16-18, 2019, among 1,998 registered voters, 61 percent said it was likely Russia would try to meddle in the 2020 presidential election -- 14 percentage points more than the 47 percent who said the same about the midterm elections in an Oct. 25-30, 2018, survey.

Between the October survey and the most recent poll, Republicans had the largest change in attitude: Forty-four percent said this month that it was likely Russia would attempt to interfere in a specific election, compared to 25 percent last year -- a 19-point difference.

But third-party election interference wouldn’t keep voters from the polling booth: Sixty-one percent of voters said they would be more likely to vote if it was determined that Russia or another country meddled in the 2020 presidential election, including 66 percent of Democrats and 64 percent of Republicans.

Suzanne Spaulding, senior adviser on homeland security for the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ international security program, said it was “encouraging” that most voters would be more likely to cast their ballot if an outside party meddled in the upcoming election.

“It may be that as we get farther away from the 2016 election that people are more willing to accept that Russia is interfering in our election,” said Spaulding, who was also a former Department of Homeland Security undersecretary during the Obama years. She said that for Republicans in particular, the issue “might have been a much more sensitive subject when we were closer to the election.”

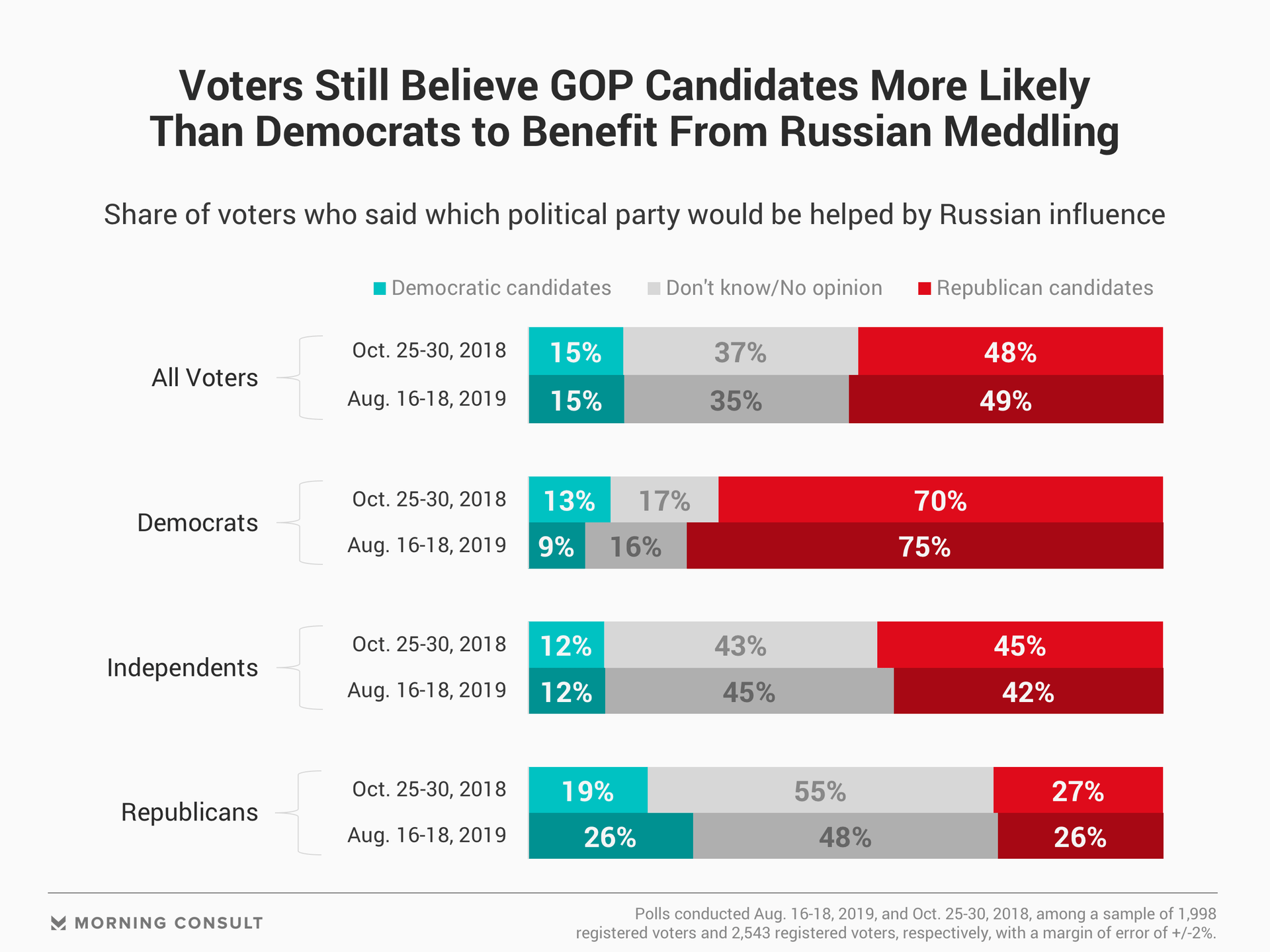

But although more voters on both sides of the aisle are inclined to say this time around that they believe that Russia will try to interfere again in the elections, they haven’t changed their minds about which party would benefit from such interference.

A plurality of voters (49 percent) said in the most recent survey that if Russia did try to influence the 2020 presidential election, it would more likely help Republican candidates than Democrats, compared to 48 percent who said the same regarding the 2018 midterms.

In the August poll, GOP voters were split at 26 percent each on whether such interference would help Republicans or Democrats. In October, 27 percent of Republican voters said it would help their candidates and 19 percent said it would help Democrats.

During his testimony before the House Judiciary Committee last month, former special counsel Robert Mueller said that Russia is already laying the groundwork for its 2020 operation “as we sit here.” That led Democrats in the Senate to try to pass election security bills, including measures requiring the use of paper ballots and funding for the Election Assistance Commission, that had already passed the House. However, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) blocked the attempts, saying the request to pass “partisan legislation” was “not a serious effort to make a law.”

Spaulding said her biggest fear heading into the 2020 election cycle is that someone will simply have to suggest that Russia interfered in order to cast doubt in the integrity of votes -- even if Russia doesn’t meddle. Looking ahead to the primaries, which start with Iowa’s Feb. 3 caucuses, Spaulding said there’s still time for state and local officials to prepare proper election audits.

“If the states are not in a position to provide a credible audit after the fact that can reassure people that their votes were counted as cast, for example, and if there’s somebody out there claiming that they figured out how to rig the system and change votes, we’re going to have a problem,” she said.

Sam Sabin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering tech.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade