Obamacare Marketplaces to See More Choices, Competition in 2022, Analysts Say

Key Takeaways

The number of health insurers offering Obamacare plans is expected to increase in 2022 for the fourth year in a row.

Analysts said uncertainty around future legislative action and the pandemic will be top-of-mind as insurers begin determining rates for 2023 coverage early next year.

About 3 in 10 registered voters say the ACA should be expanded, per new Morning Consult/Politico data.

Health insurers are expanding their offerings on the Affordable Care Act marketplaces for 2022, but preparing for a volatile year as the COVID-19 pandemic rages on — potentially affecting health coverage costs well into the future.

The individual market makes up a small share of private insurance, but those trends offer clues about how health insurers think about their overall costs for the upcoming year. Open enrollment begins Nov. 1, and this will mark the fourth year of expansions on the individual market after an exodus from 2016-18, driven in part by uncertainty around the future of the ACA and subsidies for cost-sharing payments.

By 2021, for example, there were an average of five insurers per state, up from a low of 3.5 in 2018. Health care analysts say there will be more health plan choices and competition in 2022, but note that there are plenty of variables injecting uncertainty into the insurance landscape for the next year, including policy proposals from Democratic lawmakers and the Biden administration.

In 2022, health insurance giant UnitedHealthcare, notably, is making inroads in seven new states after exiting almost every state’s exchange a few years ago. Along with Aetna, which is moving into eight states, it’s the biggest expansion for next year announced so far, according to Cynthia Cox, a vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation and director of its ACA research program.

“We're seeing more entrants than we are exits in the states we are looking at so far,” Cox said. “We've really turned a corner around this market — premiums have been holding pretty flat, and insurers are coming back into the market or newly entering.”

Health insurers are seeing a more stable regulatory environment after the Supreme Court decided to uphold the ACA in June. The Biden administration is also offering more support to get people enrolled in ACA health plans than the Trump administration did, including running a six-month special enrollment period due to the pandemic that closed in mid-August and saw about 2.8 million people sign up for Obamacare coverage.

The expansions this year indicate that insurers are “making business decisions that take the Biden administration’s commitment to growing these markets at face value,” said Myra Simon, a principal at the consultancy Avalere Health who advises health plans.

Now, the exchanges are seeing more participation than ever from consumers. Last week, the Biden administration said enrollment in ACA health plans had reached 12.2 million, the highest level since the marketplaces began offering coverage in 2014. Part of that uptick in enrollment is likely due to the expanded premium subsidies that Congress passed earlier this year and is now looking to make permanent.

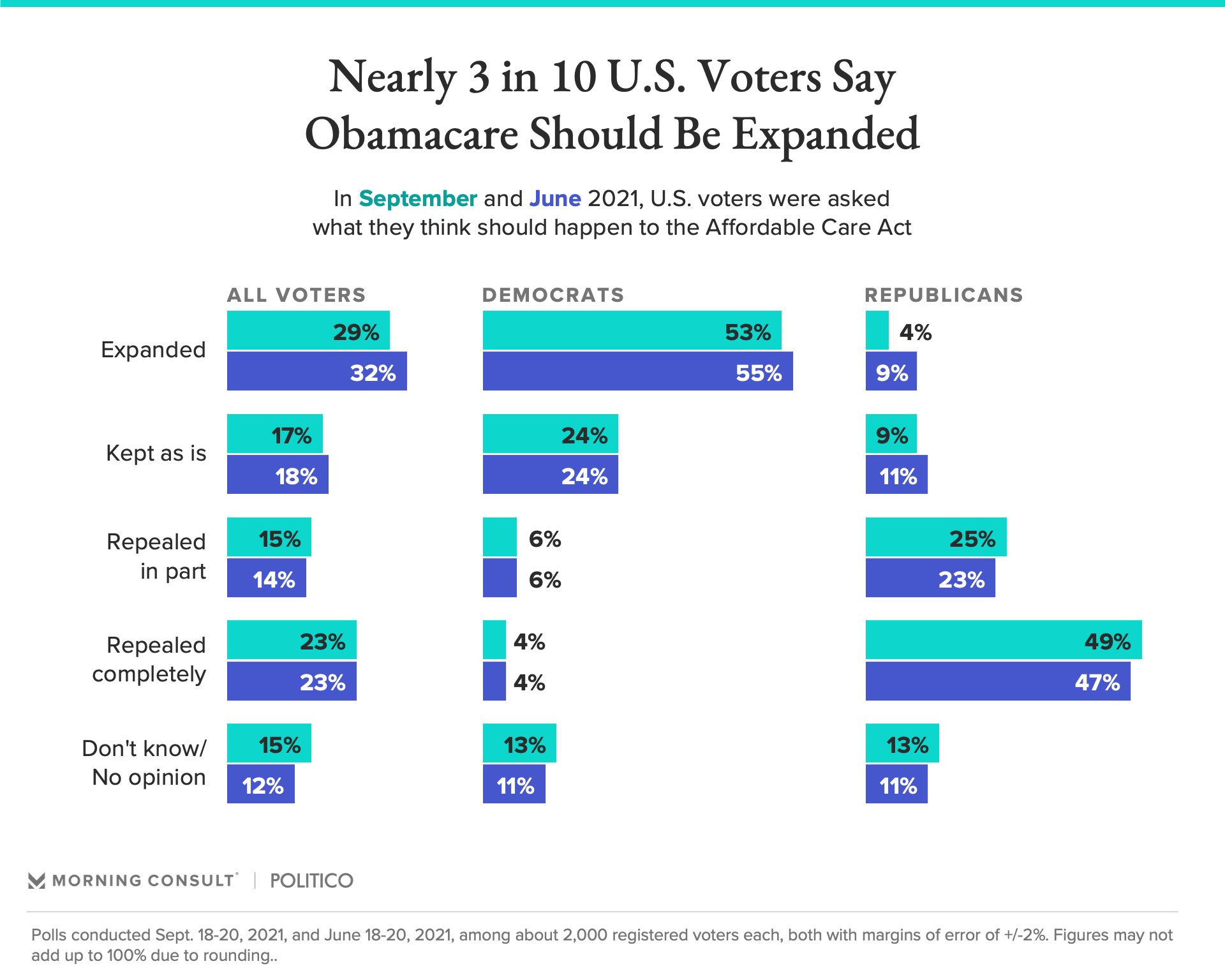

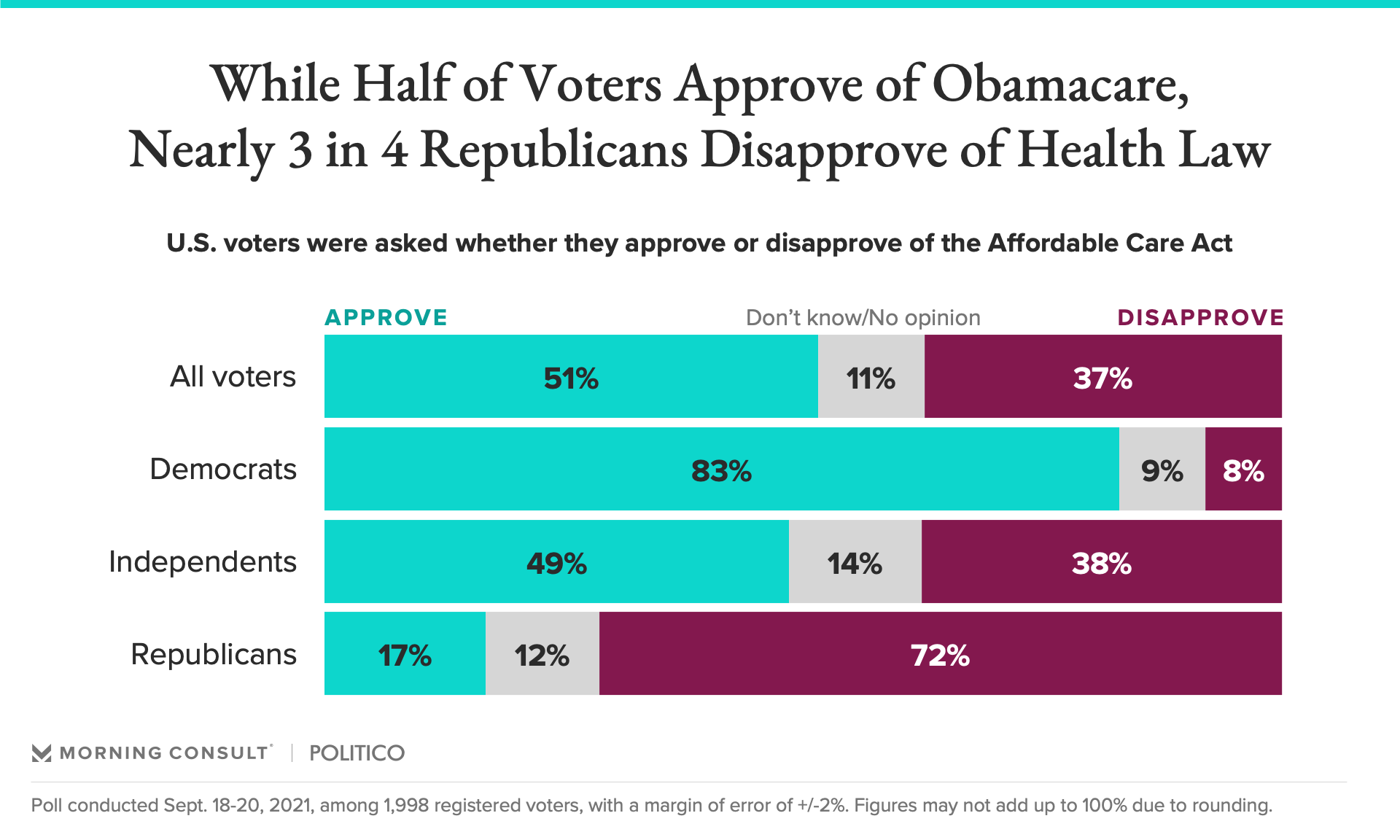

Notably, some Americans’ increased reliance on ACA programs during the pandemic hasn’t shifted public sentiment on the landmark health law. In a Morning Consult/Politico poll conducted Sept. 18-20, 29 percent of voters said Obamacare should be expanded, down 3 percentage points from June, with Democrats largely supporting expansion and Republicans most likely to say the ACA should be repealed completely.

Other legislative proposals could also boost insurers’ fortunes in 2022. Congressional Democrats are weighing a plan to fill the so-called coverage gap in states that haven’t expanded Medicaid by subsidizing marketplace coverage for people who would otherwise be eligible for Medicaid through 2024 — meaning health insurers stand to gain business in those states.

The marketplace can also be a bridge for insurers to win state Medicaid contracts and begin offering Medicare Advantage plans.

“Insurers recognize that there are a lot of people in this market who can get free coverage,” Cox said. That means there will likely be competition among insurers to offer the cheapest plans in their markets, because “if you can set the benchmark that determines that free coverage, then you're going to be one of the most attractive plans coming into the market.”

The timing for any new legislation matters, though. One of the Democrats’ top health priorities is making permanent the Obamacare premium subsidies, which are currently set to expire at the end of 2022 and could lead to many people dropping their coverage when their health costs shoot up.

If the measure doesn’t pass by early next year, insurers will be modeling the overall health of people on their plans and staring down a “riskier” pool — potentially leading to significant premium increases for 2023, Cox said.

An estimated 15 million Americans are also primed to lose their Medicaid coverage when the federal public health emergency ends because of a rule that essentially blocks states from kicking ineligible people off their Medicaid rolls during the emergency. Though the health emergency has been extended several times during the pandemic, it’s currently set to expire at the end of December.

When that happens, about one-third of those set to lose coverage would be eligible for heavily subsidized ACA health coverage if lawmakers make the enhanced tax credits permanent, according to an Urban Institute report. Even so, analysts warn that there could be delays in coverage as people transition plans, and that some are likely to be left uninsured altogether.

“Whenever eligibility changes, you get drop-offs in insurance coverage, and whenever insurance coverage changes, you get drop-offs in utilization,” said Katherine Baicker, a health economist and dean of the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy. “The more churn there is in insurance status, the greater the risk of care falling through the cracks.”

The ongoing pandemic also leaves a big question mark in the Obamacare landscape. Insurers lock in the upcoming year’s premium rates months in advance, and their initial filings indicated they expected Americans’ use of health care services to return to pre-pandemic levels, and didn’t factor extra costs or savings into their 2022 premiums.

That’s partially because the country appeared to be on a better trajectory with the pandemic.

But with the surge in COVID-19 cases across the country, Cox said the same may not be true when insurers begin determining 2023 rates early next year.

“Lagging vaccination rates and the recent spike in hospitalizations, particularly among unvaccinated people, is certainly having an upward pressure on insurer costs, which might down the road translate into higher premiums” for 2023 coverage, Cox said. “It's really hard for insurers to model this a year out, you know, which is what they will have to do.”

Gaby Galvin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.