Children’s Programming Takes Cues From Digital Outlets During Pandemic

Most children across the country haven’t been inside a classroom since March, and now many are unsure if they’ll continue to be stuck at home throughout the upcoming school year. Amid this uncertainty, educational entertainment has taken on a more important role — and the industry is embracing many of the pandemic-induced innovations as their new temporary normal for production.

From pitch to premiere, the process of developing and producing a children’s TV show can take three to five years. Necessities for larger series, such as attaching multiple broadcasters to a project to secure international distribution, contribute to this timeline. And after a show goes through development with all involved parties giving notes, production can take close to a year.

Between COVID-19 and the country’s national reckoning over racial justice, faster production of educational content for children that speaks to the zeitgeist has also become necessary, lest it appear tone deaf.

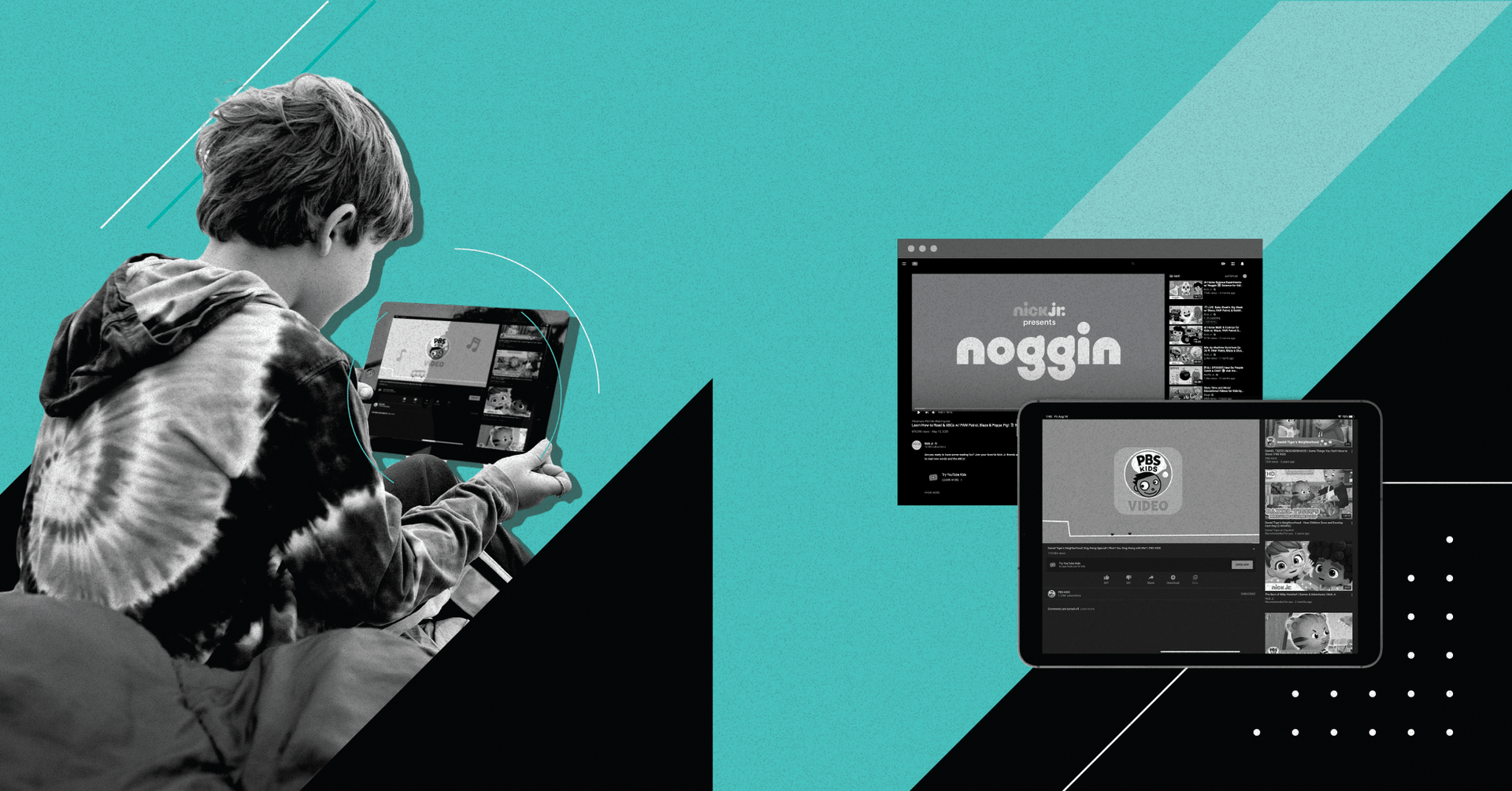

Michael Levine, senior vice president of learning and impact for Noggin, said the ViacomCBS Inc. child-focused label quickly pivoted to producing content featuring the company’s brands and characters that discuss topical issues children may have experienced in recent months. Short-form videos and special programming have touched on topics including health promotion, mask wearing and racial justice.

“We've created all sorts of different short-form content without having studios open, just because we have tools of animation that don't require us to all have to sit together in a studio,” he said.

PBS Kids was also ready with topical content. Linda Simensky, head of content for PBS Kids, said PBS was able to make both animated and live-action short-form content to educate kids about health and safety practices. In the case of animated videos, she said they repurposed existing footage from titles including “Arthur” and “Molly of Denali,” and just updated the voiceovers.

This quick turnaround marks a change within the industry. Even a 30-minute animated program can take anywhere from six to nine months to produce, Simensky said. Additionally, if shows have an educational lean — and many do — they need additional time to ensure they are meeting educational standards set forth by child development experts.

“You have to put together a framework, and then work with some experts to make sure the information is correct and work with the child development expert to make sure you're teaching the right things to the right age group,” she said.

All of PBS Kids’ shows, such as “Odd Squad” and “Sid the Science Kid,” undergo this often costly process.

Budgets for animated programs can range from low to upper six figures, while the budget for live-action shows can top out in the millions.

“We've been looking for quite a while at that development cycle and thinking three to five years” is no longer sustainable, said David Kleeman, senior vice president of global trends at Dubit, the digital studio and research strategy consultancy focused on kids and teens.

As children have gravitated toward content on platforms such as YouTube, they’ve become accustomed to a constant stream of fresh content. With YouTube and other digital spaces, creators can produce content much faster than traditional outlets.

“What kids are often watching is a YouTuber who wakes up in the morning and says, ‘OK, I'm going to do a cooking show today,’ and by noon has a cooking show up. Their development cycle is about four hours,” he said.

COVID-19 has provided an opportunity to accelerate even digital-first processes.

Kleeman cites the YouTube program “Lockdown” as one example. The show was conceived, shot and released in roughly six weeks, according to Kleeman, with actors filming themselves on smartphones and footage pieced together remotely, which shattered the three-to-five-year window. It also explores the timely topic of life for kids during a pandemic, something Kleeman said is part of a larger trend.

“There's such an interest right now in media being timely for kids and in understanding the world around them,” he said. “They were forced into making some of these adaptations during lockdown and what they've seen from them is, these are good things. These are important to kids.”

But Simensky is cautious about replicating such shortcuts with long-form content just to say something was finished faster.

“You can only really get away with that for a very specific reason where you're trying to get something out very quickly,” she said. “They're not bad techniques, but it's not necessarily what you'd use in a series.”

She said PBS Kids has been trying out new methods of production as it works on its documentary “PBS KIDS Talk About: Race and Racism,” and has learned that it can create content with a smaller crew in a “faster, more focused” way.

Levine said the children’s television industry can look to how other genres of programming are adapting to the COVID-19 era to improve upon the changes it has already made

“People have really been innovating with the existing tools during this time,” he said.

“There are a bunch of new best practices that I think will be incorporated and will make media production more efficient and less costly in the future.”

Sarah Shevenock previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering the business of entertainment.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade