The Vaccine Holdouts: Who They Are and What’s Fueling Their Opposition

Key Takeaways

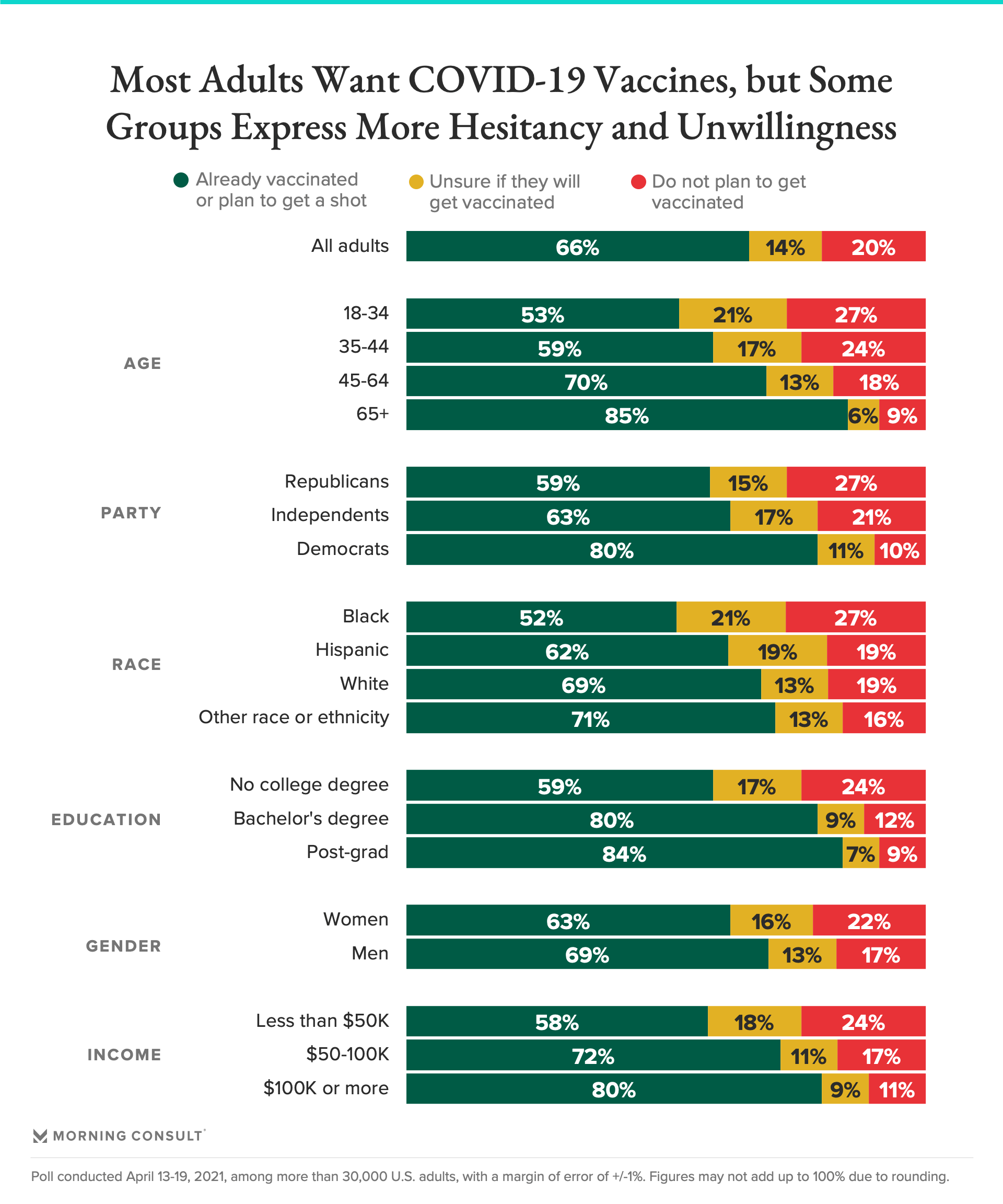

1 in 5 adults say they don’t plan to get a COVID-19 vaccine, while 14% are unsure.

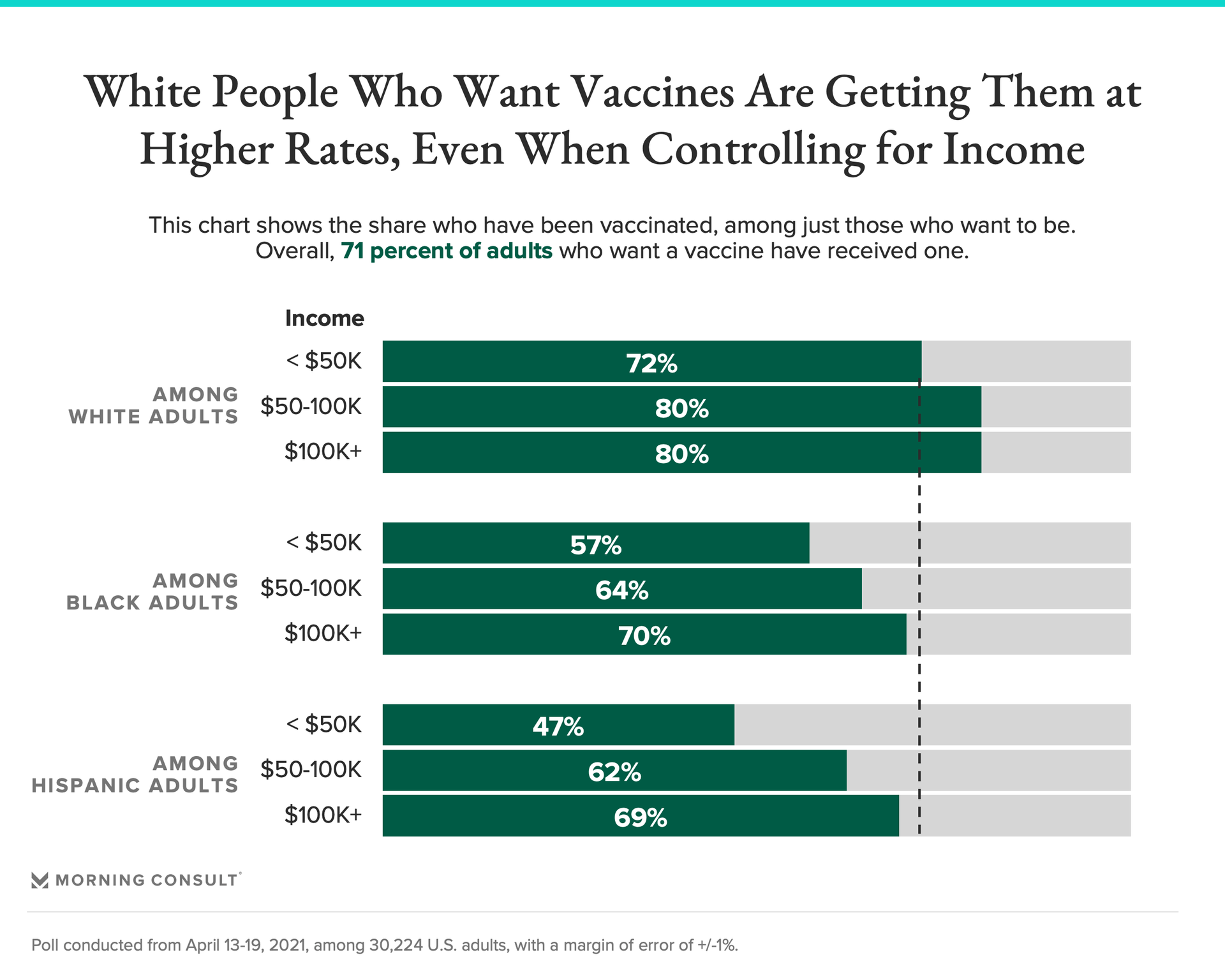

77% of white adults who want a shot have gotten one, compared with 60% of Black adults and 55% of Hispanics who want one.

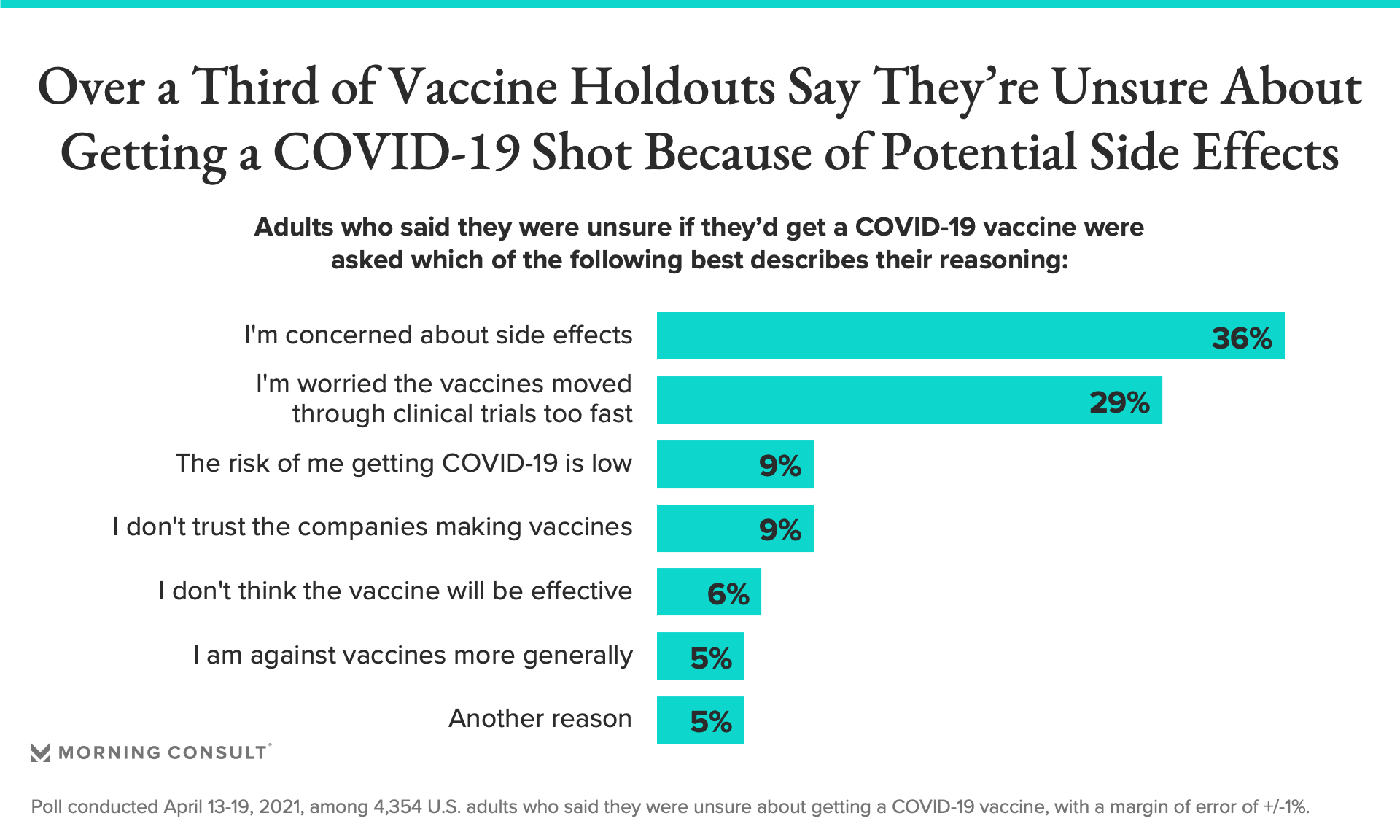

Among adults who are unsure about getting vaccinated, 36% said they are concerned about potential side effects, while 29% said they are worried that the vaccines moved too quickly through clinical trials.

Mothers, adults under 45 years old who earn less than $50,000 annually and Republicans and Black adults without college degrees are some of the groups most likely to say they’re unsure or unwilling to get vaccinated.

Morning Consult is surveying more than 30,000 U.S. adults every week to explore how the country’s COVID-19 vaccination effort is playing out among a broad swath of Americans. The findings reveal the nuanced relationship between vaccine reluctance and access across demographic groups and geographies.

The COVID-19 vaccine floodgates are now open, with more than half of U.S. adults receiving at least one dose and the public and private sectors pouring billions of dollars into the effort. Yet there are also major gaps in who’s actually gotten a shot, and officials are already trying to reach vaccine holdouts -- a group that will help determine how severe the country’s COVID-19 threat will be going forward.

A new Morning Consult analysis, drawn from a survey of more than 30,000 adults and conducted April 13-19, indicates that while most people across demographic groups want a COVID-19 vaccine, both vaccine reluctance and access to shots are causing friction in the rollout.

Among the groups most likely to say they’re unsure about getting vaccinated or plan to skip the shot altogether: Republicans and Black adults without college degrees; Black women; Hispanic women who are Republicans or political independents; adults under 45 years old who earn less than $50,000; mothers; and adults in a handful of states, including Mississippi, Idaho and Arkansas.

There’s limited overlap. Even after controlling for race and income, for example, people without a college degree are 143 percent more likely than someone with a postgraduate degree to say they don’t plan to get vaccinated. And controlling for income and education, Black adults are 41 percent more likely than white adults to say they won’t get a shot.

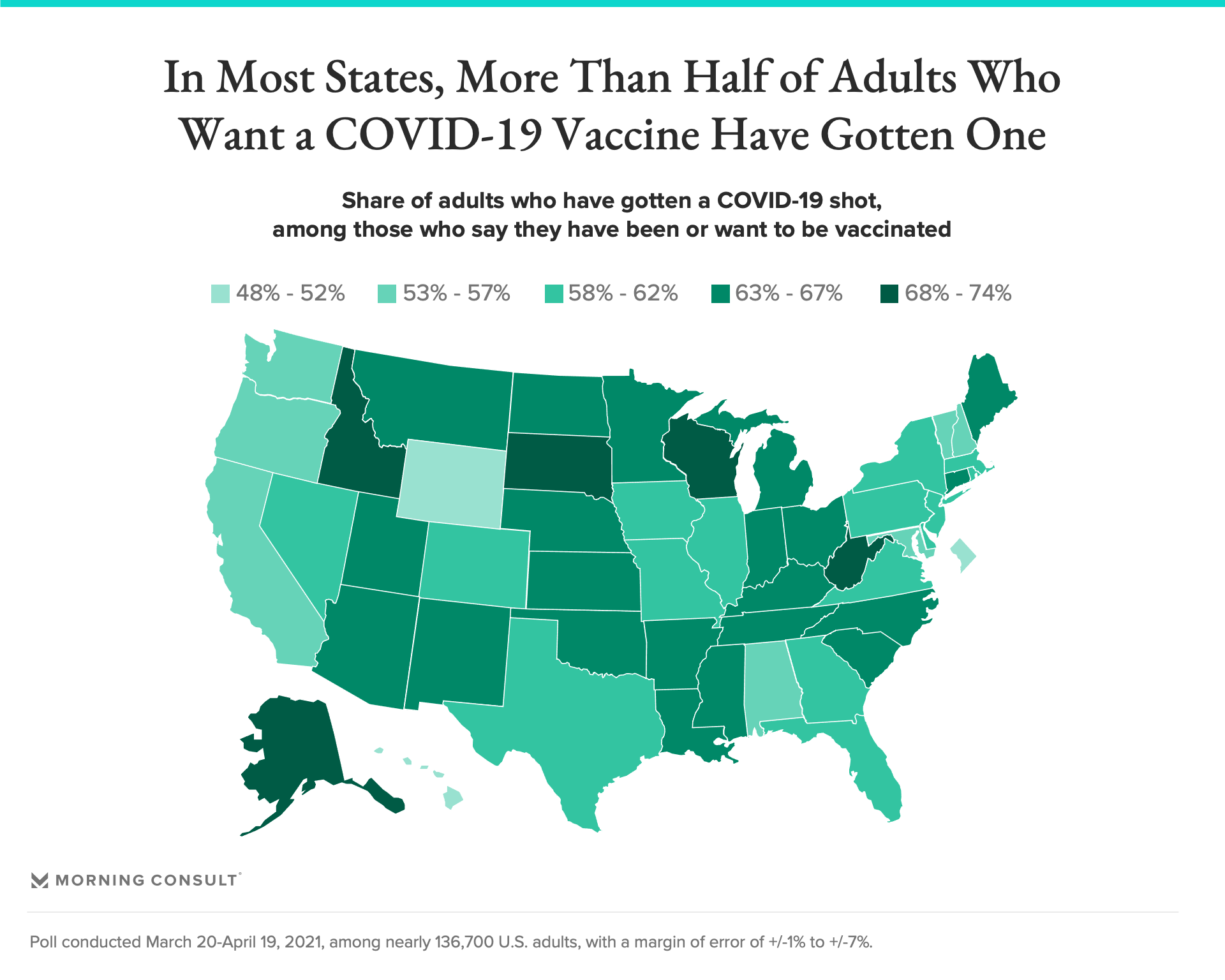

“What troubles me is that these are national totals,” said Dr. Mildred Solomon, a bioethicist and president of The Hastings Center. Vaccine reluctance is higher in some pockets of the country, while some states have been “surprisingly slow to deliver, even to the people who want to be vaccinated.”

Across the board, the most common reason cited by people unsure about getting vaccinated was concern over potential side effects, followed by worry that the vaccines moved too quickly through clinical trials. There were some differences among groups: Reluctant Republicans were more likely than their Democratic counterparts to be worried about the speed of clinical trials, 35 percent to 26 percent.

Meanwhile, hesitant Black adults were about twice as likely as whites to say they don’t trust the companies making the vaccines, 15 percent to 7 percent, and hesitant Gen Z adults were more likely than older people to say they’re at low risk of getting COVID-19.

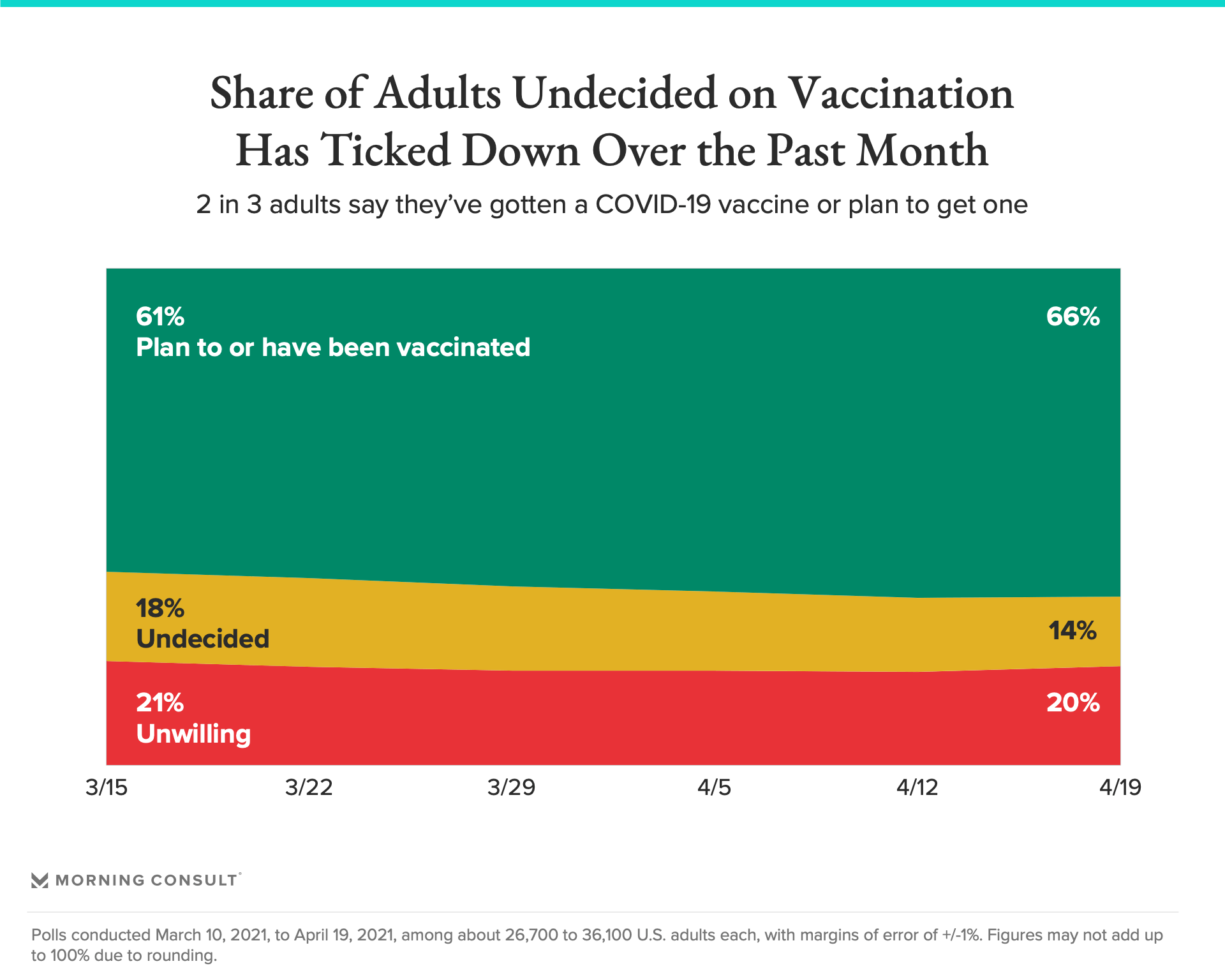

Despite the lack of trust some have in vaccine manufacturers, the pause on Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine rollout doesn’t appear to have dampened people’s enthusiasm for COVID-19 shots. Overall, 66 percent of adults say they’ve either been vaccinated or plan to get a shot -- a share that is level with the week before -- while 14 percent are unsure and 20 percent have no plans to get vaccinated.

“We know that some individuals will be reluctant to use this vaccine, even if we come out with a favorable response, because of the pause,” said Dr. José Romero, who chairs a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advisory committee tasked with reviewing data for J&J’s vaccine and recommending whether the hold should be lifted.

“I think that the vast majority of people will understand that this is a good thing to have, and will feel reassured,” Romero said.

Even so, Marc Morial, president and chief executive of the National Urban League and former mayor of New Orleans, cautioned that the ultimate decision to seek a COVID-19 shot doesn’t necessarily translate to trust in institutions, because “people are weighing the pros and cons” of getting vaccinated.

The survey suggests that vaccine access is at least as big of a problem as vaccine hesitancy. When looking only at adults who said they’re in favor of getting a shot, white people were more likely to say they’ve been vaccinated than adults who are Black, Hispanic or of another race or ethnicity, the data shows.

Overall, 71 percent of U.S. adults who want a shot have gotten one. But those levels range from 77 percent among white adults to 60 percent among Black adults and 55 percent among Hispanics.

The racial gap persists across income levels, but is widest among people making less than $50,000 annually: 72 percent of white adults in that group who want a shot have gotten one, compared with 57 percent of Black adults and 47 percent of Hispanic adults in that income range. Among those making $100,000 or more, those figures are 80 percent among white adults, 70 percent among Black adults and 69 percent among Hispanics.

The findings track with CDC data showing vaccination rates for Black and Hispanic adults are lagging behind rates for white adults.

“We overstated the hesitancy issue,” said Dr. Georges Benjamin, the longtime executive director of the American Public Health Association. “It's still important, but we overstated it and understated the structural access issues.”

Otis Rolley, senior vice president of The Rockefeller Foundation’s U.S. equity and economic opportunity initiative, said the emphasis on vaccine hesitancy puts the burden on individual people rather than on institutions that should be providing information about the shots and making it easy for people to get vaccinated.

Some of the vaccination inequities can be traced to the early rollout. In the Houston area, for example, the first shots were administered by local hospitals and other health care providers that started vaccinating their existing patients, excluding “the most vulnerable people who have never been to the hospital because they can't afford it,” said Frances Valdez, who leads Houston in Action, an advocacy and organizing group that is receiving funding from The Rockefeller Foundation through a new $20 million vaccination program.

Even now, “there are people that want vaccines that don't have access,” Valdez said.

In parts of the country, vaccine access and willingness are intertwined. In rural communities, for example, adults making less than $50,000 who are in favor of vaccination are less likely than those earning above $100,000 annually to have actually gotten a shot, 68 percent to 86 percent.

In Oklahoma, which opened vaccinations to nonresidents this month, 66 percent of adults who want to be vaccinated have already gotten a shot, according to the Morning Consult analysis. But the state also has among the highest levels of outright vaccine opposition in the country, with 28 percent of adults saying they don’t plan to get the shot at all. Four other states -- Mississippi, Idaho, South Dakota and West Virginia -- have the same or higher levels of vaccine opposition.

“This is a setup for dangerous clustering of infections, like islands of infection, in different states or regions,” Solomon said. “That's going to affect everybody's safety. These regions have porous boundaries.”

Time is running short to reverse those trends: New COVID-19 cases are rising faster in rural counties than in urban ones, according to a USA Facts analysis.

“From a rural standpoint, we've got to change the messaging, and this has to be addressed at a community level,” said Alan Morgan, chief executive of the National Rural Health Association. “This needs to happen today, not four to six months from now.”

Despite the urgency, these are likely to be long-term challenges. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that everyone who actively wants a shot will have gotten one within the next two to four weeks. And as the vaccination sprint slows to a trickle, public officials and the medical community will be tasked with identifying, and vaccinating, the final holdouts.

“That last 20 percent of any public health campaign is tough,” Benjamin said. “They need to plan for that now.”

Data scientist Haley Sorensen contributed.

Gaby Galvin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade