Coworking Spaces Up Safety Precautions, Go Digital to Stay Alive Amid Pandemic

Since its inception in the mid-2000s, the modern coworking movement has aimed to create a community for small businesses, solo workers and teleworkers looking to log on somewhere besides their living rooms.

But since the coronavirus crisis has raised concerns about shared spaces and surfaces, the industry is undergoing a transition that emphasizes the importance of staying connected while working from home, albeit by embracing virtual communities as opposed to physical ones.

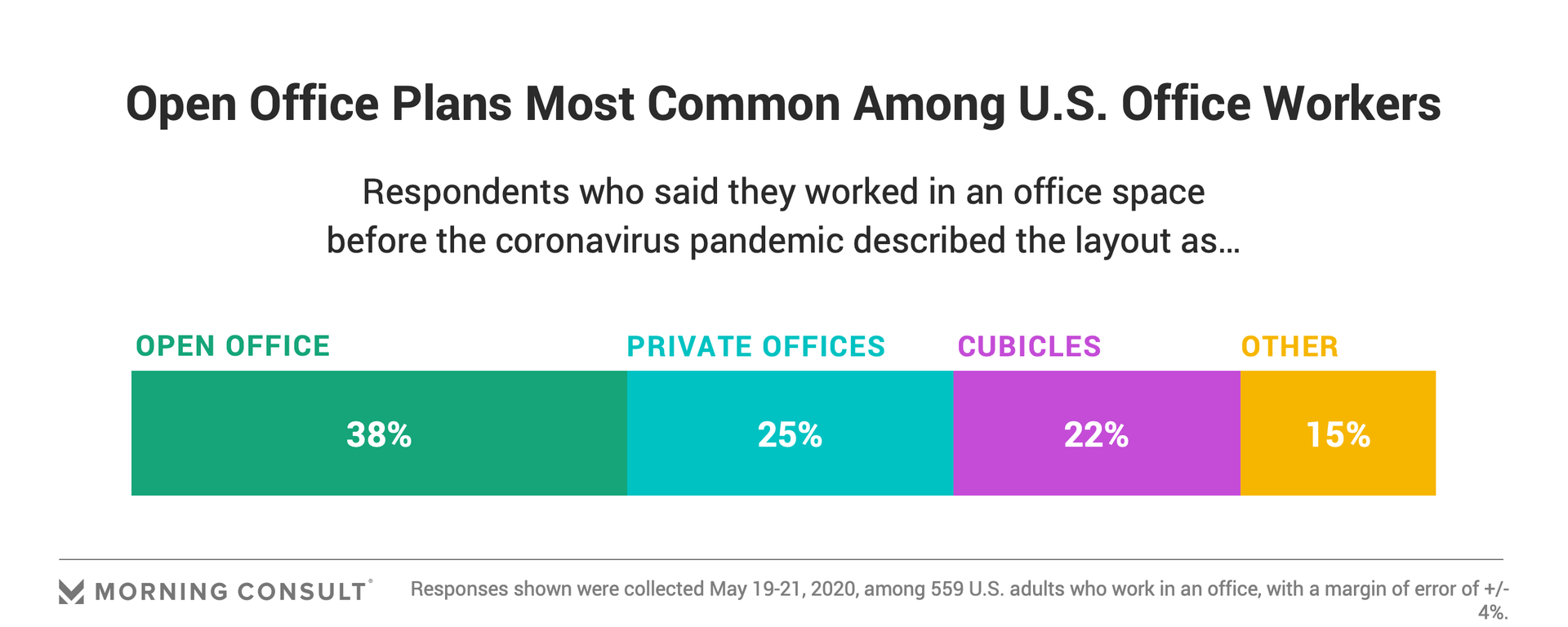

Before the pandemic, even traditional corporate offices were moving away from the classic cubicle layout in favor of more collaborative workspaces.

Morning Consult polling found that before the coronavirus crisis, roughly 2 in 5 U.S. adults who said they worked in some sort of office space said that space was part of an open office environment shared by several people. Nearly half (47 percent) said they either worked in a private office where people worked in separate rooms, or in an office with cubicles.

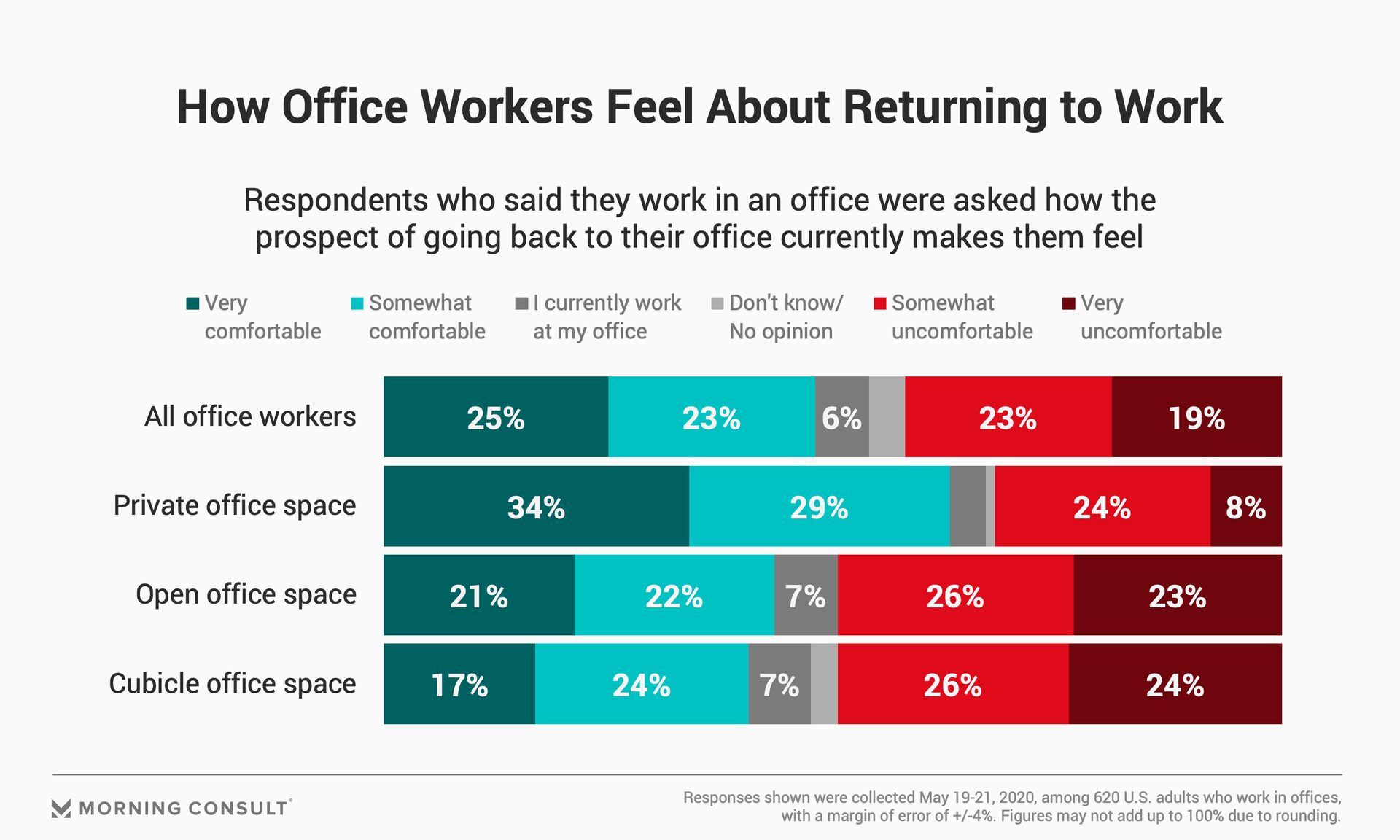

But social distancing guidelines meant to curb the spread of COVID-19 have led to a significant uptick in working from home, and a reticence to return to physical workplaces persists amid fears about the disease.

This is particularly true of those who work in more open office spaces, which many coworking spaces facilitate. The May 19-21 poll found that employees who work in private, walled-off offices are more comfortable returning to work, compared to those who head to open-office or cubicle environments. The poll was conducted among 2,200 U.S. adults and has a margin of error of 2 percentage points.

But coworking companies are optimistic that they can hold on to their members and continue growing by upping safety policies and providing digital communities.

Technology could help workers feel more comfortable in coworking spaces

Workbar LLC, a coworking space with nine locations in the greater Boston area and one in San Francisco, is relying on its suburban offices to attract companies with employees who might be less eager to commute into cities post-pandemic, said Chief Executive Sarah Travers.

Only two of Workbar’s Massachusetts spaces are located in the city of Boston. The company has purposefully invested in suburban locations after hearing from members that they prefer working closer to home rather than commuting into the city, according to Travers.

“I think we will see a surge in demand of people who do not want to get on public transit and commute into the city, and people will flock toward suburban areas closer to their homes,” she said.

Since some Workbar members are considered essential employees, the company has been allowed to keep its offices open but unstaffed throughout the pandemic, although it encouraged all members who are not essential workers to stay at home. Workbar will begin staffing its locations again on June 1, and has already installed several new safety features, including desk dividers and touchless thermal scanners, at some locations, which use infrared technology to take a person’s body temperature.

Workbar is also reintroducing a density tracker it used on its subscriber platform about 10 years ago, shortly after it was founded, so members can check to see how many people are in their office before deciding to go in.

Safety is paramount, but community building is essential to the coworking industry

While safety has become the main point of emphasis for many coworking companies and businesses across industries, community engagement has long been at the heart of the coworking movement, said Tony Bacigalupo, who in 2007 founded New Work City, the first coworking space in Manhattan, and who now speaks and advises on the topic.

“We are an interdependent species,” Bacigalupo said. “We need other people to survive and to thrive.”

For that reason, Bacigalupo said coworking spaces should invest in their online community offerings while large-scale in-person socialization is off the table — and many already are.

Workbar, which used to host community events daily before the pandemic, shifted to virtual programming on its Workbar Live platform just three days after Boston shut down on March 15.

Dayhouse Coworking, which opened in spring 2019 with the goal of catering to working parents, also made all of its events virtual around mid-March, and has since decided to make the option permanent, said founder Jen Luby.

The Highland Park, Ill., company now offers a “Work From Home” membership for $29 per month, which allows members to access daily digital programming, such as lunch-and-learn events, happy hours and worksprints during which members set a timer to accomplish tasks together. Dayhouse’s in-person membership plans range from $39 to $349 per month.

New members and current physical space members alike are taking advantage of the work-from-home membership option, with participation in that program about five times higher than the number of members using the physical space during shutdown, Luby said.

The $29 monthly fee for remote workers is a suggested price, Luby said, and while most members pay in full, others have opted to pay less based on what they can afford. Others are still paying dues even if they aren’t going into the office.

“That really kept us going,” Luby said. “But our revenue is dramatically down. Even though our members kept paying dues, we lost out on all the daily passes and conference room rentals, which was a big portion of our revenue before.”

Dayhouse’s revenue is down about 60 percent for closed months, Luby said, but she’s hopeful her company will soon attract parents looking for alternative work spaces throughout the summer months and potentially longer with children at home.

Standing in sharp contrast with Dayhouse’s sole location, coworking giant WeWork oversees more than 800 locations in 120 cities, including 70 locations just in Manhattan.

WeWork has also remained open for essential workers, adding safety measures such as staggering seating to ensure distance, installing additional sanitization tools in high-touch areas and adding signage including one-way arrows in hallways to keep members at a safe distance, a spokesperson said. (Morning Consult has offices in WeWork buildings.)

Some coworking companies opt to stay virtual for the time being

Indy Hall, a coworking space in Philadelphia, is in no hurry to reopen. Co-founder Alex Hillman said in an email that they’ve been focusing all of their efforts on improving their online community, which members can access for $20 per month, with coffee discussions, productivity challenges, entertainment events and more while its physical space is closed.

Before the pandemic, more than 60 percent of Indy Hall members came into the office only once a month or less, Hillman said, so the company currently sees more potential risks than benefits in reopening. Those members would pay $30 per month for once-a-month access, while other in-person memberships ranged from $120 to $300 per month.

“I am having a hard time being enthusiastic about reopening,” Hillman said. “I think that spaces who really embrace these shifts have a much better chance of being around long term.”

Although Hillman said it’s difficult to compare Indy Hall’s “@Home” member numbers with physical memberships since there is so much overlap, he said that since the start of lockdowns, the company has seen about 30 to 40 members gathering virtually each morning, which he estimates is at least four times as many as those who typically gathered in the kitchen.

Cove, another coworking company with four locations in Washington, D.C., and one in Boston, also launched “Cove @ Home” two months ago for all of its clients, and is taking a similar slow approach to physical reopening, said Chief Executive Adam Segal. The home membership plan costs $65 per month, while access to the office ranges from $79 to $229 per month when the space is open.

Cove’s virtual programming includes monthly gift boxes of snacks or wine, which members are encouraged to consume while socializing on the company’s virtual happy hours.

The coworking industry likely has a difficult few years of recovery ahead, Segal said, but with many companies already so well-positioned to take advantage of digital offerings that make their spaces safer and their communities more accessible, the pandemic has also created an opportunity for coworking.

“The office more broadly really needs to give people a reason to go in,” Segal said. “In the short term, people are definitely looking for flexibility and companies are looking for flexibility if they’re not locked into a long-term lease. Coworking can provide that.”

And with much of the workforce now accustomed to doing work outside of the office, coworking companies also anticipate that after the pandemic, alternative workspaces will become a more viable option for a wider range of companies.

“I do think that coworking spaces are a very valuable resource for people,” said Travers, the Workbar chief executive. “No one is going to work out of a Starbucks anymore. No one is going to work out of a space that isn’t designed for your health and safety.”

Alyssa Meyers previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering brands and marketing.