Could Influencers Help Campaigns Sidestep Social Media Crackdown on Political Ads?

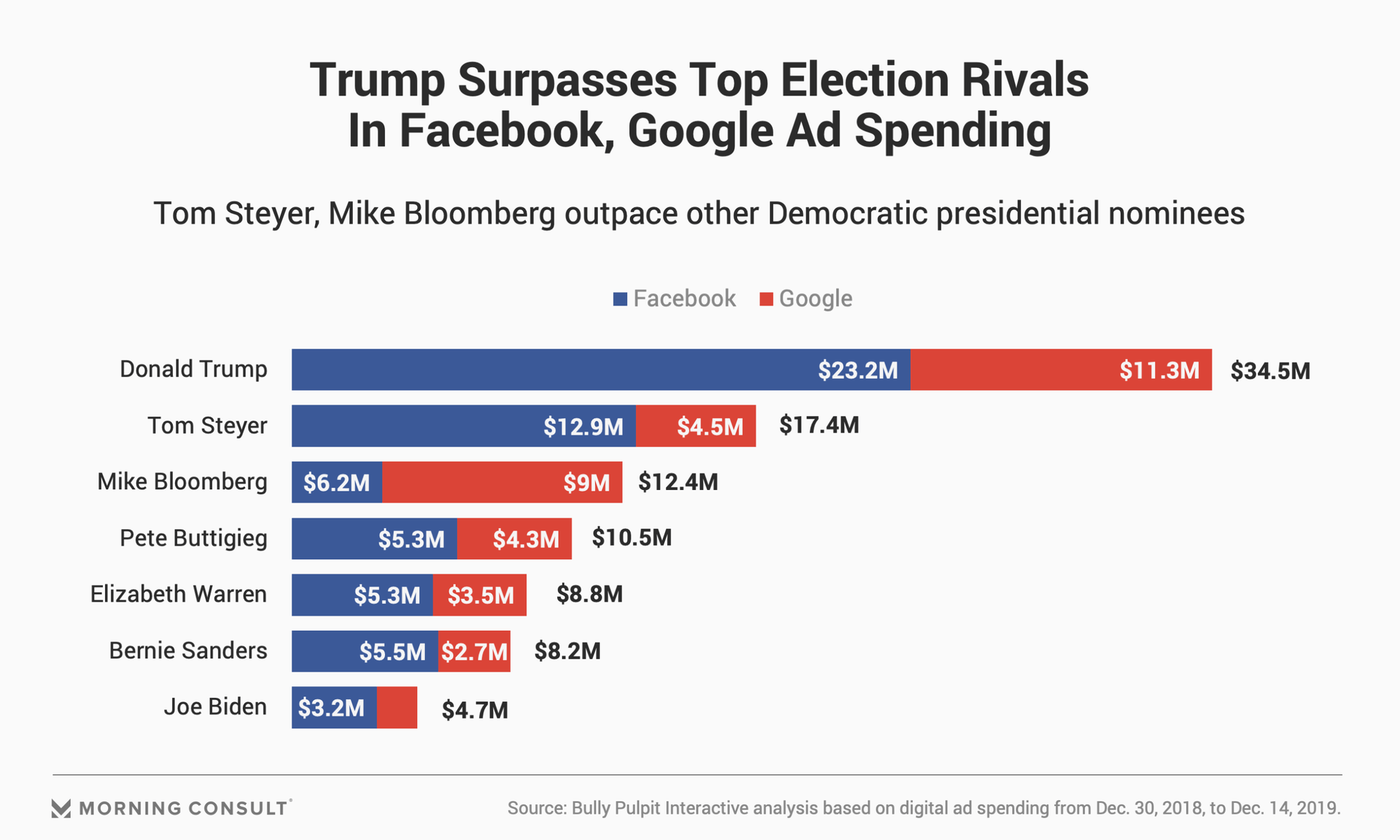

With a Federal Elections Commission that lacks the necessary quorum to create rules for online political ads ahead of 2020, social media companies have been making attempts to combat disinformation by regulating their own political ad systems -- Twitter Inc. banned political ads altogether earlier this year, while Google decided to prohibit political ads starting in January that target users based on age, gender and postal code.

Yet there's at least one advertising tool that marketing experts say campaigns can use to combat new industry rules: social media influencers.

“People will be looking for solutions to still reach these social media-heavy audiences” now that targeting options are being restricted, said Isaac Simpson, content strategy director at Los Angeles-based experiential marketing firm NVE Experience Agency, whose clients include Adidas AG, Lyft Inc. and Netflix Inc. “A great way to reach those social media-heavy audiences is through influencers.”

A Twitter spokesperson confirmed that while political advertising is banned, political influencer marketing is still allowed on the platform, so long as no paid promotion is attached to it. And a Google spokesperson said the platform approaches influencer marketing on YouTube in the same way it does editorial content, and all creators are asked to check a box if their videos include any paid product placements or endorsements.

Although campaigns on Google can still target audiences in other ways, Simpson, who previously led creative at Las Vegas-based influencer marketing agency Influential, said the company’s micro-targeting ban could mean partnerships with YouTube influencers will become more valuable to campaigns as an alternative.

The crackdown on political ads comes at a time when industry experts say influencer marketing was already starting to attract more attention from political campaigns looking to target younger voters. For example, NextGen America, the progressive political action committee founded by Tom Steyer to mobilize young voters, was already planning before the digital ad policy changes to work with 3,000 micro-influencers, primarily on Instagram, in 2020. It has no current plans to increase that number in response to the actions of Google and Twitter.

Tegan O’Neill, NextGen’s director of digital communications, compared her organization’s response to the rapid changes in the digital political ads landscape to a cooking show. “You give us a turnip and a cup of coffee and we’ll figure out how to turn it into good ads,” she said.

And NextGen, she said, has diversified its advertising strategy enough that digital ad limits are unlikely to hurt the organization. “Something we know from doing this work for a long time is that we need to be layering tactics no matter what we’re doing,” she noted. “Google and Twitter’s ad restrictions are just another reason that we need to emphasize programs like this influencer program.”

But influencer marketing experts and researchers warn that there’s at least one obvious risk for advocacy groups and campaigns turning to influencers: There are no disclosure guidelines for political influencer marketing, leaving campaigns to default either to those laid out by the Federal Trade Commission for corporate entities or the FEC’s political advertising rules for traditional ad buys.

James Nord, founder and chief executive of New York-based influencer marketing agency Fohr, said when the agency worked with the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee during the 2018 midterms, the DCCC’s lawyers opted for the latter, adding lengthy “Paid for by” disclosures to their influencer posts.

But such lengthy disclosures could hamper an influencer’s authenticity, which Nord said is key to this type of political advertising.

“To have someone that you trust talk about something like politics and the need to vote or why a specific candidate is more appealing than another, that carries more weight,” Nord said.

He cited an effort from United We Win as the perfect example of a failed political influencer campaign. The group drew heavy public criticism when BuzzFeed reported last month that the super PAC was advertising an opportunity on influencer platform AspireIQ for any qualified influencers to be paid to endorse Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) for president.

That’s why it’s important to find an influencer with a personal connection to whatever cause is being promoted, Nord said, especially as the digital political ads landscape continues to change.

“If Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, everyone said we're not doing political advertising anymore, there would be a big desire for campaigns to make sure that they had a voice inside of those platforms,” Nord said. “And I could definitely see influencers becoming part of that voice.”

But the Wild West of political influencer marketing won’t be around forever: As political campaigns look to 2020, an increased reliance on political influencers could be the “forcing event” that prompts Washington to prioritize influencer marketing issues, according to Roberto Cavazos, the executive-in-residence at the University of Baltimore’s Department of Information Systems and Decision Science, who published research on fraudulent influencer marketing in July.

The FEC did not respond to a request for comment.

Unlike the Fyre Festival, whose influencer-driven social media campaign in 2017 promised a luxury music festival but instead left attendees stranded with half-built huts and cheese sandwiches in the Bahamas, Cavazos said influencer marketing in the 2020 election has the potential to “damage democracy” if abused.

“Imagine a scenario where some community has some issue, and they have social influencers, and one gets angry at somebody and all of a sudden they’re producing deepfakes or they’re becoming malicious,” Cavazos said. “Those kinds of things are going to be the wake-up call” for regulators and policymakers to look at the space more seriously.

Sam Sabin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering tech.