Most Voters Don’t Want False or Misleading Political Ads to Stay on Social Media

Key Takeaways

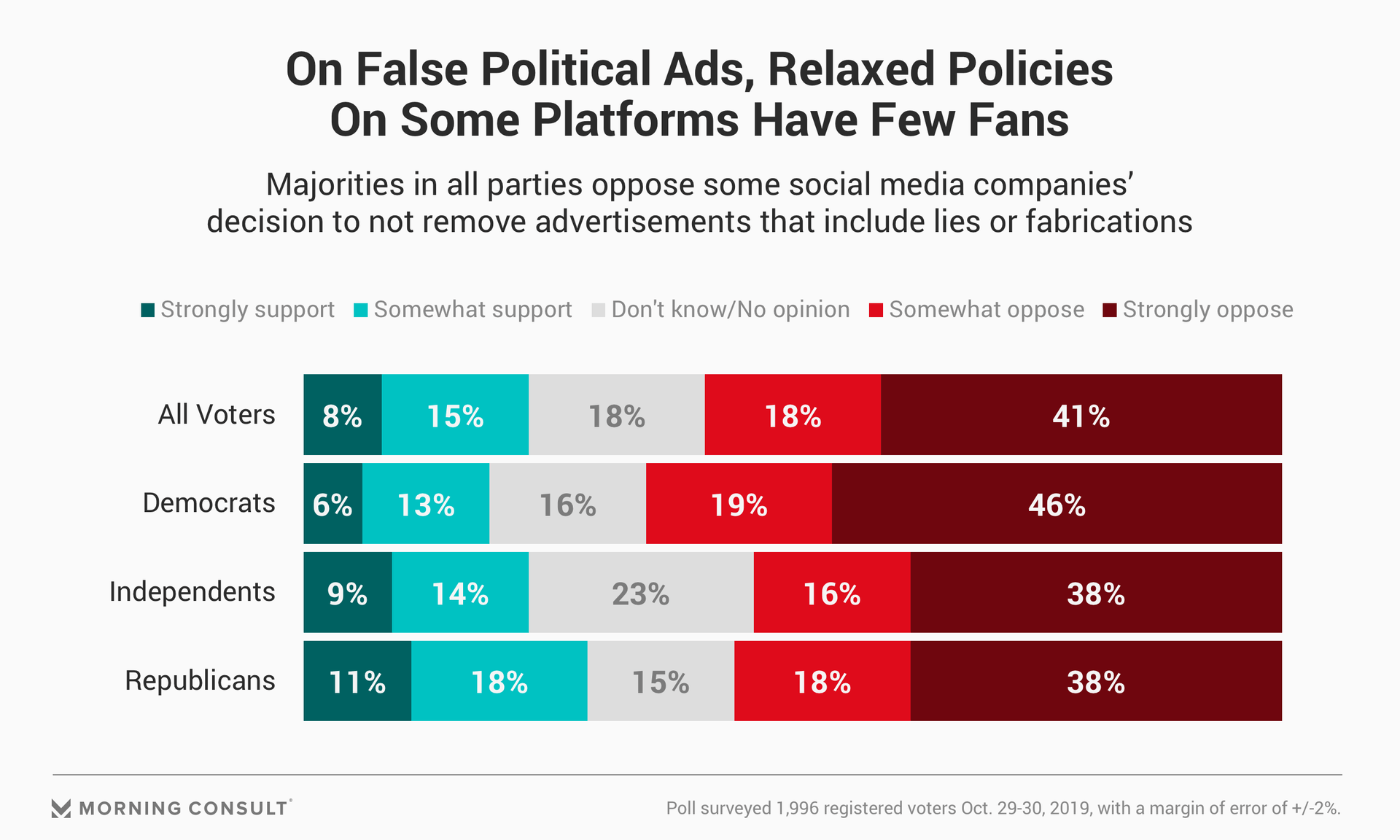

65% of Democrats and 56% of Republicans were against keeping political ads with lies or fabrications on social media sites.

77% of voters said they’d support a law prohibiting ads with falsehoods on social media.

When Twitter Inc. Chief Executive Jack Dorsey announced Wednesday that his platform would no longer support political advertisements -- just one hour before Facebook Inc.’s scheduled earnings call with investors -- it was widely seen as a jab at Facebook’s divisive decision to not fact-check advertisements on its site from candidates running for political office.

And a new Morning Consult survey shows voters might be on Dorsey’s side of the ad policy debate: Fifty-nine percent of registered voters said that they oppose social media platforms choosing to not remove political advertisements including lies or fabrications.

The survey, conducted Oct. 29-30 among 1,996 registered voters, overlapped with Dorsey’s announcement. And there was bipartisan consensus on political ads: Sixty-five percent of Democrats, 54 percent of independents and 56 percent of Republicans said they oppose leaving such advertisements online.

Facebook Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg defended his company’s political ad policy within the first five minutes of his call with investors, saying “I don’t think it is right for private companies to censor politicians or the news” and that it would be better to “try and increase transparency” of advertisers. The comments from Zuckerberg on the issue follow his testimony before the House Financial Services Committee last week and a speech at Georgetown University about free expression on Oct. 17.

Currently, social media companies are under no federal obligation to ensure that the advertisements on their platforms include factual information, much like cable network operators. Public broadcasters such as ABC, NBC and CBS, however, are bound by the Communications Act of 1934 from censoring advertisements from political candidates, even if they include falsehoods -- a mandate that a 41 percent plurality of all registered voters said they oppose in the Morning Consult survey.

But a strong majority of voters (77 percent) say they would back a law ensuring that all advertisements on social media platforms are factual, including those from candidates running for public office. Eighty-one percent of Democrats and 77 percent of Republicans said the same.

The Federal Election Commission’s efforts to regulate online political ads, which included proposed rules for political ad disclaimers, have stalled since the agency effectively shut down in late August after Vice Chairman Matthew Petersen resigned and left the FEC without its legally mandated minimum of four commissioners. With that, social media companies have largely had to fend for themselves on the issue.

But Dorsey’s unprecedented move of banning all political advertisements on Twitter starting on Nov. 22, with plans to unveil the official policy by Nov. 15, has been met with support from Democrats. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), who grilled Zuckerberg on the issue during last week’s House hearing, tweeted that Dorsey’s decision was a “good call” and that “if a company cannot or does not wish to run basic fact-checking on paid political advertising, then they should not run paid political ads at all.”

And Bill Russo, a spokesperson for former Vice President Joe Biden’s presidential campaign, said in a statement that the campaign appreciated Twitter’s acknowledgement that “they should not permit disproven smears, like those from the Trump campaign, to appear in advertisements on their platform.”

On the other side of the aisle, however, Brad Parscale, campaign manager for President Donald Trump’s re-election bid, said in a statement that the new policy was “another attempt to silence conservatives, since Twitter knows President Trump has the most sophisticated online program ever known,” and called it “a very dumb decision” for Twitter’s stockholders.

J. Nathan Matias, an assistant professor of communication at Cornell University who focuses on digital governance, said in a statement that he’s worried a law tackling online political advertising could have unintended consequences if the definition of political ads is “too loose” or if enforcement is “too clumsy.”

“Twitter is still important to civic discourse, so campaigners, ad agencies, and manipulators will find other ways to influence people,” he said. “We will probably see more bots, organized tweeting campaigns, and hybrid human-software coordination on Twitter, especially if organizers think they can influence the company's algorithms.”

Sam Sabin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering tech.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade