No Schlubs Like Me: Americans Don’t Like Politicians In Debt

Key Takeaways

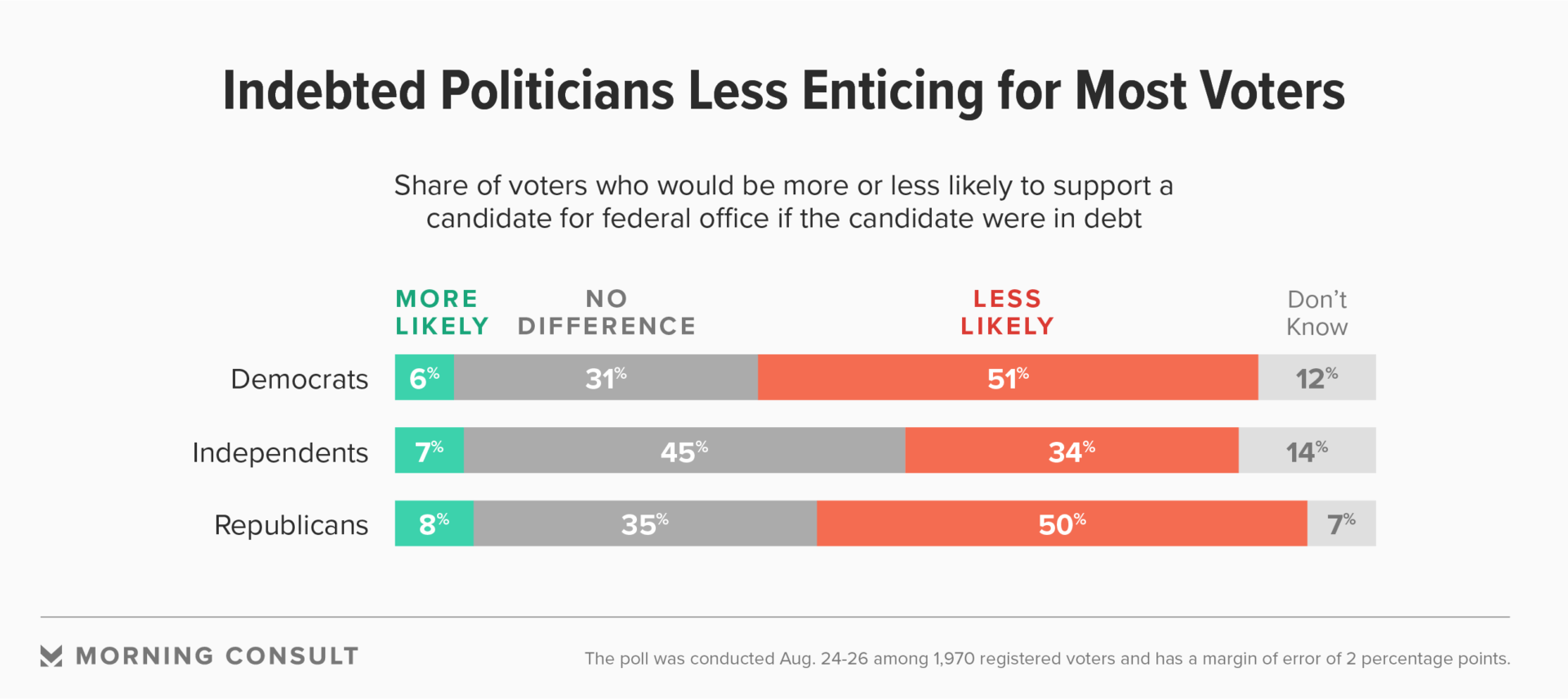

In poll, plurality of 45% of registered voters say they’d be less likely to vote for a candidate in debt, versus 6% who say the opposite.

77% of Americans have some kind of debt, according to a Fed survey, with credit cards and car loans most common.

In 2015, the median member of Congress had a net worth at least nine times larger than the median American; but a survey suggests that specifying what kind of debt a candidate holds could ameliorate the stigma by making the issue personal.

Stacey Abrams, the Democrat running for governor of Georgia, a traditionally red state, made a plea to voters: to not judge her for her debt.

In an April op-ed in Fortune, Abrams, who would be the nation’s first female black governor if elected, said her more than $200,000 credit card, student loan and tax debt made her like most Americans, and highlighted the systemic issues that make it hard for minorities and women to get ahead.

In contrast, Republican ads have painted her debt as a sign of financial irresponsibility. Her GOP opponent, Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp, said in August that Abrams’ move to give money to her own campaign instead of paying back taxes to the Internal Revenue Service should be “criminal.”

That GOP message against indebted candidates may resonate, according to a Morning Consult survey that asked 1,970 registered voters from Aug. 24-26 whether various personal traits would make them more or less likely to vote for someone.

The trait that stood out as most negative for a potential candidate: being in debt. Out of a subsample of 678 registered voters, a plurality of 45 percent said they’d be less likely to back a candidate in debt, while 6 percent said they’d be more likely to, tying it with “lobbyist” as the most negative personal attribute out of 66 included in the poll. (The subsample’s margin of error is 4 percentage points.)

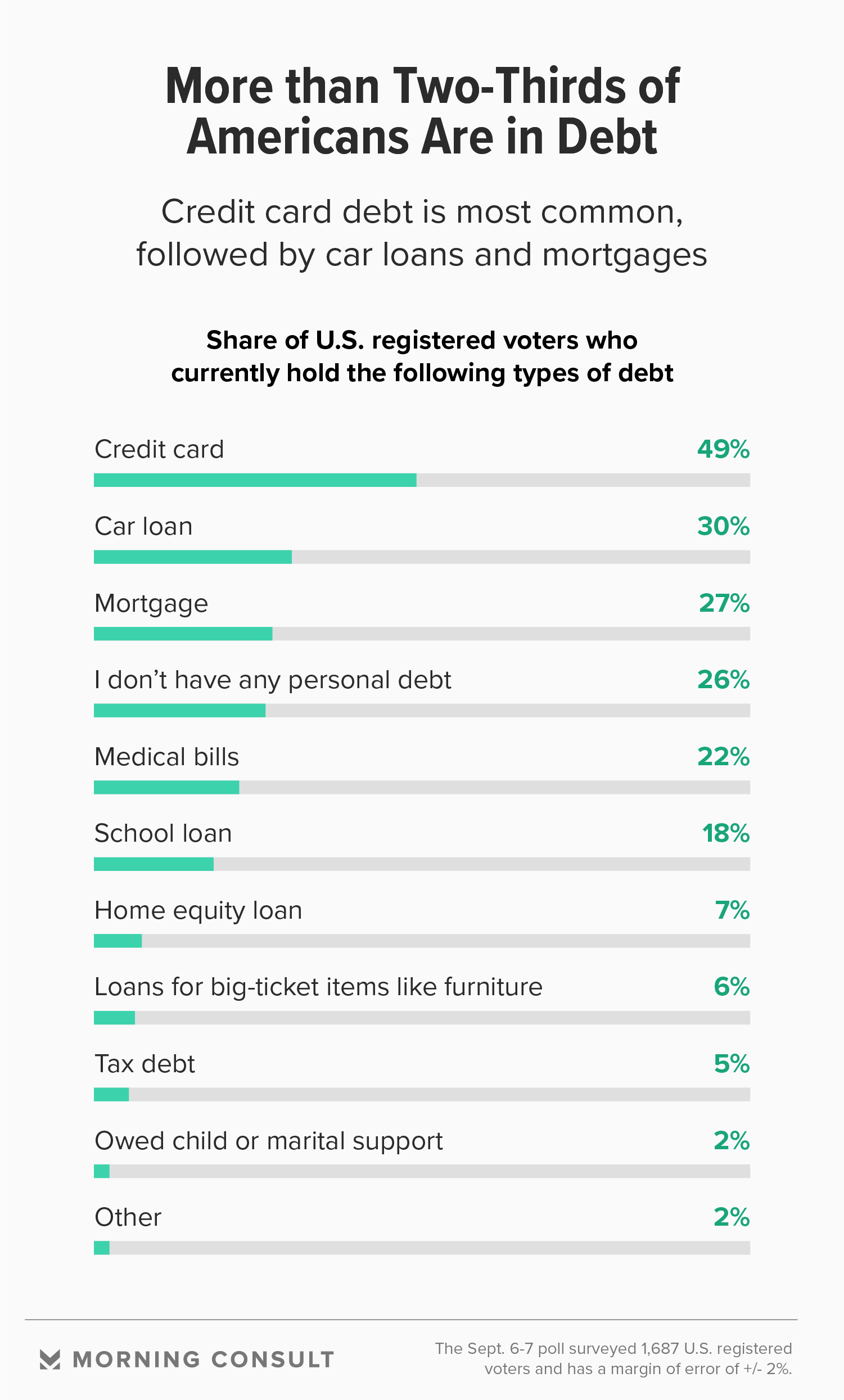

But most people hold some kind of debt: A separate Morning Consult survey of 1,687 voters from Sept. 6-7 found that just 26 percent said they had no personal debts.

“There’s a weird thing in our culture that we tend to want to have political leaders who feel are a little better than us,” said Jonah Goldberg, who writes about political and cultural issues at the American Enterprise Institute. “I think it’s a human thing because we want to put our leaders on a kind of pedestal. Debt pings a suspicion in people’s minds: Is this guy or gal actually better than me, or are they a schlub like me?”

Voters’ negative attitude toward debt comes even as numerous studies have shown the average American is piling on car, credit card and student debt nine years after the Great Recession ended. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York found household debt levels last year spiked above their previous peak in 2008 and rose to $13.29 trillion in the second quarter of this year.

A separate Fed Survey of Consumer Finances from 2016, the latest year available, found that 77 percent of families had some kind of debt, similar to 2007 levels.

“We are a country of self-loathing debtors,” said Louis Hyman, an associate professor at Cornell University who wrote “Borrow: The American Way of Debt.”

The Sept. 6-7 poll backs up the same idea: Even though most voters reported having debt, they viewed it negatively. Sixty percent agreed with the statement that debt reduced opportunities and was an obstacle to providing for oneself and one’s family, versus 40 percent who agreed debt was necessary and could expand opportunities.

“One of the interesting things about it is, even though you can see it as a strictly economic question, for most people it’s a moral question,” Hyman said. If a candidate has a lot of debt, that may suggest to voters that the person would be bad at managing finances or more susceptible to bribery, he said.

To voters, the words “in debt” can be “code for not rich, or lacking in personal responsibility,” Goldberg said, but for one notable exception: wealthy candidates.

Though the Aug. 24-26 survey showed most voters (59 percent) said it wouldn’t matter if a candidate were wealthy, Goldberg said, “We may not say it; we may be embarrassed by it, but we tend to have a soft spot in our hearts for rich candidates.”

For example, President Donald Trump has talked about “how he was the king of debt,” he said. “And I think you can have mass amounts of debt, so long as people think you can handle it.”

U.S. politicians tend to be wealthier than the average American. The Center for Responsive Politics reported in its most recent analysis in October 2017 that the median net worth of a U.S. senator was $3.13 million in 2015, while the median House member was worth $888,508.

That compares to a median net worth of $97,300 for an American family in 2016, according to the Fed’s consumer finance survey.

To illustrate the tendency to differentiate debt held by rich people and average people, some experts also pointed to this adage: “If you owe the bank $100, that's your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, that's the bank's problem.”

The average politician is likely to fall in the second category. Among candidates running for office in the November midterm elections, or defending their seats, mortgages of hundreds of thousands of dollars -- or a loan against collateral of as much as $25 million, in the case of Ohio’s GOP Rep. Jim Renacci -- are more common than smaller loans for credit cards or education, according to personal financial disclosures.

For example, in the dozen most contested Senate races, the only candidate or incumbent to report a student loan was Kyrsten Sinema, the Democratic representative running for a seat in Arizona, while her GOP challenger, Rep. Martha McSally, was the only one to report credit card debt, which she said was paid off in February.

That’s in contrast to the average American voter: The Morning Consult survey in September found almost half (49 percent) of voters reported having credit card debt, with car loans the second-most common debt.

But Amanda Litman, co-founder of Run for Something, a progressive group that encourages millennials to seek higher office, said the group’s experience with candidates shows that many voters welcome younger candidates who talk about their own student loans or medical bills.

“It’s an indicator of something larger broken with the system as opposed to a personal failing,” she said about those kinds of debts.

Morning Consult’s September survey suggests that this tactic of more personally connecting a candidate’s financial situation could help ameliorate the negative connotation attached to debt.

When specifically asked if personal debt such as school loans or credit card debt would make people more or less likely to vote for an elected official, a plurality of 44 percent said it would make no difference, while 26 percent said they would be less likely.

“The reality is if we want candidates who aren’t old, rich white men to fund their way into office, we have to be more accommodating and encouraging to people who have gone through what most Americans have gone through,” she said.

Anna Yukhananov previously worked at Morning Consult as an editor for features and policy coverage.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade